Nearly three months after seizing power, and more than two months after announcing an interim government, the Taliban regime in Afghanistan has not been formally recognized by a single country. It risks becoming a pariah, just as it was in the late 1990s when it controlled Kabul but had formal relations with only three countries—Pakistan, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia. If recognition does come from the international community this time around, it is more likely to be conferred by countries in Afghanistan’s neighborhood than by the United States or other Western countries.

To Recognize or Not to Recognize

In international law, recognition generally means viewing a government as lawful, legitimate, in full control of its territory, and deserving of formal membership within the international community. However, in reality, many different factors inform decisions about recognition.

The United States (and much of the West) will base future decision about Taliban recognition on human rights and inclusivity considerations. The Taliban government, which isn’t about to compromise on its fundamental ideology, is unlikely to meet these conditions. Consequently, U.S. recognition of the Taliban government is a long shot. Regional players are more likely to eventually opt for recognition, due to geographic factors. However, for now, they’re taking a wait-and-watch approach, in particular to see if there are sustained improvements in security, before making any decisions.

The U.S. and Recognition

Prior to the Taliban takeover, U.S. officials said the group would not earn legitimacy if it took power by force—implying that recognition would come if the Taliban gained power through peaceful means, presumably through a power-sharing arrangement emerging from negotiations with the Ashraf Ghani government.

Few in Washington could have anticipated that the Taliban would take power peacefully because of the complete and rapid collapse of the Afghan republic, not through a negotiated settlement or formal transfer of power. The Biden administration has indicated it’s not currently prepared to recognize the Taliban government. Officials suggest recognition will come only if the Taliban take actions that promote inclusivity (meaning non-Taliban leaders, including women, are brought into the government) and human rights, especially women’s rights.

If recognition does come from the international community this time around, it is more likely to be conferred by countries in Afghanistan’s neighborhood than by the United States or other Western countries.

One may argue that conditioning recognition on rights is misguided, given that Washington often recognizes and works closely with brutal and repressive regimes. But from the U.S. perspective, the Taliban case is different.

First, most of Washington’s relationships with repressive regimes have served U.S. interests—from Cold War partnerships with anticommunist dictatorships in Latin America to more recent alliances with authoritarian states in the Middle East that help tackle Islamist terrorism. However, Washington has less of a compelling interest to pursue partnership with the Taliban. President Biden has bluntly stated that bigger U.S. priorities lie elsewhere, beyond Afghanistan—from fighting climate change to managing competition with China.

Additionally, the Taliban take brutal to another level. They harbor close ties to—and command the deep respect of—transnational and regional terrorist groups like al-Qaeda and the Pakistani Taliban. Their Haqqani Network faction, which currently controls the interior and refugee ministries, is a U.S.-designated terrorist organization implicated in multiple mass casualty attacks on Americans. Some Taliban policies—like banning older girls from attending school—are unheard of in any other country, including Saudi Arabia.

And yet, Washington’s main interests in post-withdrawal Afghanistan require engagement with the Taliban. It needs the Taliban to ensure safe passage for remaining U.S. citizens wishing to evacuate. It needs assurances from the Taliban that they won’t obstruct the delivery and distribution of humanitarian supplies. The Biden administration hasn’t indicated a desire for Taliban assistance for counterterrorism efforts against Islamic State-Khorasan (IS-K)—a shared rival—but the pursuit of intelligence cooperation can’t be ruled out if Washington doesn’t secure basing arrangements or intelligence-sharing deals with Afghanistan’s neighbors.

To circumvent the engagement-without-recognition dilemma, Washington is depending on the CIA. State Department officials can’t negotiate with a government with which Washington has no diplomatic relations. The CIA, however, can engage covertly. Officials can invoke plausible deniability if reports surface about U.S. talks with the Taliban. However, the administration has not denied two CIA-led exchanges with the Taliban—a meeting with CIA director Bill Burns and talks with Taliban leaders in Doha led by a delegation headed by the CIA’s deputy director.

The Region and Recognition

Because of their location, Afghanistan’s neighbors and other regional players have stronger incentives than the United States or other Western countries to formally engage with the Taliban government. Recognition would facilitate cross-border trade and new infrastructure investments; enhance border security cooperation; and provide more opportunities to work with the Taliban to minimize the risks of undesirable spillover effects. These include refugee flows, cross-border terrorism, and narcotics trafficking. These risks are less urgent for America, which enjoys the luxury of distance.

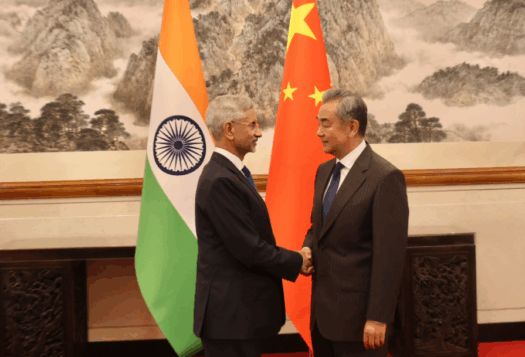

However, to this point, regional players have eschewed recognition, instead engaging in ways that fall short of normalization. Officials from Russia, China, Iran, Pakistan, and the Central Asian states have met with Taliban leaders. Islamabad has even invited Taliban officials to take up diplomatic posts in Pakistan.

Ironically, while regional players may think recognizing the Taliban government can better position them to work with the Taliban to reduce security risks, they’ll likely hold back from recognition until they have assurances about the broader security situation. For regional actors, the litmus test for recognition will be security, just as it will be rights for the U.S.

They’ll want to see if the Taliban can ease severe humanitarian and economic crises, resolve internal divisions, curb terrorist threats, and more broadly succeed in consolidating power. If it doesn’t achieve any one of these goals, security could deteriorate, spawning destabilizing outcomes from heightened refugee flows to new armed resistance movements. Destabilization would reduce regional players’ abilities to operate in Afghanistan, negating a benefit of recognition.

Afghanistan-based terrorism is a major concern for regional actors. All worry about IS-K. Beijing worries about Uighur militants, and Islamabad about the Pakistani Taliban (TTP). New Delhi worries about anti-India groups.

Ironically, while regional players may think recognizing the Taliban government can better position them to work with the Taliban to reduce security risks, they’ll likely hold back from recognition until they have assurances about the broader security situation.

If and when they conclude they’re satisfied with security conditions, expect some regional players to start considering recognition. The top candidates are Pakistan, the Taliban’s longstanding sponsor, along with China, which has engaged closely with the Taliban in recent years. The Taliban’s mediation of a new month-long truce between Islamabad and the TTP, and reports that the Taliban have started addressing Beijing’s concerns about Uighur militants, increase the likelihood that Pakistan and China will be two of the first countries prepared to recognize the Taliban. Russia and Iran may not be far behind, but Tehran will be more cautious given its concerns about the safety of Afghanistan’s Shia community, and the lack of Shia representation in the government.

There are several outliers. Tajikistan, which has taken a strongly anti-Taliban position, largely for domestic political reasons, and is hosting Afghan resistance leaders, is unlikely to recognize the government regardless of the security situation. Same with India, given the Taliban’s close relationship with Pakistan; the Taliban’s past attacks on Indians in Afghanistan; and New Delhi’s limited channels of communication with the Taliban.

An Urgent Test for Recognition

Debating the issue of Taliban recognition is not a purely academic exercise. Afghanistan’s devastating humanitarian crisis—which the World Food Program director recently described as the world’s worst—underscores the real-world stakes at play. The international community has concluded that it can deliver humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan without recognizing the government, because it can work with UN agencies and private charities on the ground and avoid sending aid directly to the government.

However, Afghanistan was dependent on international assistance for 75 percent of public funding before the Taliban takeover. It badly needs broader development and financial assistance, not just food supplies and other humanitarian aid, to stabilize its economy and bring relief to its masses. For the United States, giving Kabul access to aid—including nearly USD $10 billion in foreign reserves frozen by Washington—is hard to justify without recognizing the regime. In effect, decisions about recognition will have a direct impact on the well-being—and the very lives—of millions.

***

Click here to read his article in Urdu.

Image 1: U.S. Department of State via Flickr

Image 2: MFA Russia via Flickr