For the second consecutive time, India boycotted the Chinese-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) forum held late last month. India’s broad objections regarding the Chinese megaproject have been two-fold. First, India has claimed that the project lacks transparency in terms of its geopolitical and financial objectives. Second, being part of the project, particularly the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) that runs through territory disputed between India and Pakistan, disregards India’s core territorial and sovereignty concerns. While China maintains that India’s rejection of the project is not going to affect bilateral ties, Sino-Indian tensions are exacerbating South Asia’s infrastructure development woes. In a region already scrambling for connectivity, Sino-Indian competition is marginalizing a better scope for networks, trade, and integration. One such affected sub-region has been Northeast India. While it is at the tri-junction of South Asia, Southeast Asia, and China, connectivity and industrial development in the sub-region have been abysmally low. Although efforts have been made by the political leaders of Northeast India to seek Chinese investments, objections by the central government in New Delhi and Sino-Indian rivalry have incapacitated progress.

Untapped Potential of China-Northeast India Ties

In 2014, then Assamese Chief Minister Tarun Gogoi remarked that Northeast India deserves a more consolidated share of Chinese investments, emphasizing that not only does the region share an international border with China but it also has cultural overlaps with India’s northern neighbor. There are two further reasons that explain the demand for Chinese investments in Northeast India. First, although the region is slowly developing, it has long been ignored by the Indian state and still lags behind the rest of the country in terms of infrastructure, power generation, and ease of doing business. Northeast India is landlocked between a developed China and a fast developing Southeast Asia and thus, the demand for investments from China is high because Beijing has proven its strength in industrialization and modernization. Secondly, Northeast India, China, and Southeast Asia make a contiguous unit in which trading and business opportunities may potentially be easier. While the withdrawal of colonial powers and modern borders discarded erstwhile trading ties, the geographical location of Northeast India can be harnessed to leverage the economic opportunities its neighbors present. A testimony to this opportunity was the brief opening of a long-lost trade route in 2015 that connected China to Southeast Asia via Northeast India.

However, such a foreign policy bargain has rarely worked in the past due to the way the Indian state is set up. Article 246 of the Indian constitution gives the central government total power over foreign policy. There is also no concrete institutional mechanism that authorizes states to control or create such policy. However, Indian foreign policy is gradually becoming more decentralized due to the demands of globalization and liberalization, and regional governments have been assertive in reaching out to foreign governments for investments. In a recent case, a delegation of political and business leaders from Northeast India, led by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s General Secretary Ram Madhav, visited Chinese city Guangzhou. The delegation invited limited Chinese investments into the region via consumer goods while also offering China sea route access to Northeast India. While the plan is focused on connecting Northeast India to the Bangladeshi port of Chittagong, it could be seen as China’s gateway to the Indian Ocean through the region.

Strategic Realities: Sino-India Rivalry

It is difficult for the central government in New Delhi to separate economic benefits from strategic concerns when it comes to cooperating with China in Northeast India. With a Northeast India plagued by insurgency, connectivity woes, and a lack of infrastructure, leaving the door to China could have strategic implications in the region that New Delhi would not consider a viable policy option.

Although flourishing investments and connectivity would benefit Northeast India and galvanize its economy, the history of Sino-Indian relations impedes the possibility of a more integrated region. The most significant bone of contention is the unresolved border dispute between India and China. The state of Arunachal Pradesh, in Northeast India, has time and again been claimed as South Tibet by China. Moreover, the scars of the 1962 war have dented regional perception, which is wary of China’s expansionism–the recent Doklam standoff is a crucial testament to the territorial anxiety between the two nations. Spirits were raised after the Wuhan summit between India and China in April 2018 and analysts debated whether India was softening its stance on the BRI and could invite limited Chinese investments under the project. Although the visit of the Northeast delegation seemed to indicate this, there are two reasons why it cannot be considered a loosening of India’s official position on BRI. First, the delegation made no official remark about the BRI and the visit was labeled as an opportunity to promote bilateral relations, which aligns with the central government’s stance of tactfully avoiding any association with BRI. Second, the delegation admitted that contesting territoriality is an obstacle to ties, particularly citing the case of Arunachal Pradesh as a challenge.

It is difficult for the central government in New Delhi to separate economic benefits from strategic concerns when it comes to cooperating with China in Northeast India. With a Northeast India plagued by insurgency, connectivity woes, and a lack of infrastructure, leaving the door to China could have strategic implications in the region that New Delhi would not consider a viable policy option. India has been apprehensive of Chinese road construction at the triangular junction of India, China, and Bhutan and this was seen as a step towards China attaining a capability to strangulate the Siliguri Corridor. In the face of a conflict like situation, Chinese control over this strategic corridor runs the risk of cutting the Northeast from the Indian mainland. The history of links between China and secessionist leaders from Northeast India has also played a huge role in raising New Delhi’s apprehension.

India is not averse to multilateral initiatives and connectivity projects but it has repeatedly underscored the strategic dimension underpinning Chinese initiatives – be it debt-trap diplomacy or geopolitical supremacy. While India has previously cooperated with China on infrastructural connectivity projects like the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM-EC), established in 1999 and graduated to Track-I in 2013, Beijing subsuming the project under the BRI did not help progress.

New Delhi’s preferred option would be to integrate Northeast India with the Indian mainland and supplement its economic development by linking it with Southeast Asia under its Act East Policy rather than to link it to China. In fact, India has teamed up with its trusted partner Japan to develop the region’s road infrastructure, which has ironically invited Chinese objections on similar grounds that India has propounded with CPEC.

Win-Win Cooperation?

Chinese investments need markets that can be provided by Northeast India. Similarly, if New Delhi wants to turn the Northeast into a manufacturing hub, it has to open up to China for markets and make use of its geographic position. Hence, mutual benefit is on the cards.

But Sino-Indian competition complicates the picture. Since Beijing is unlikely to accommodate India’s concerns about BRI, Northeast India’s aspirations may be a casualty of that deadlock. Under such circumstances, it is essential that the sub-region of Northeast India is first imagined at a bilateral level by India and China. To do this, New Delhi will have to balance cooperation and competition with China by inviting selective investments that do not directly impact its security and territorial concerns. It can further balance Chinese capital with Japanese investments. For China to enter the markets of Northeast India, it has to generate confidence in New Delhi that it will forego territorial contestations. China also has to look beyond BRI as a vehicle of integration and development in the region.

***

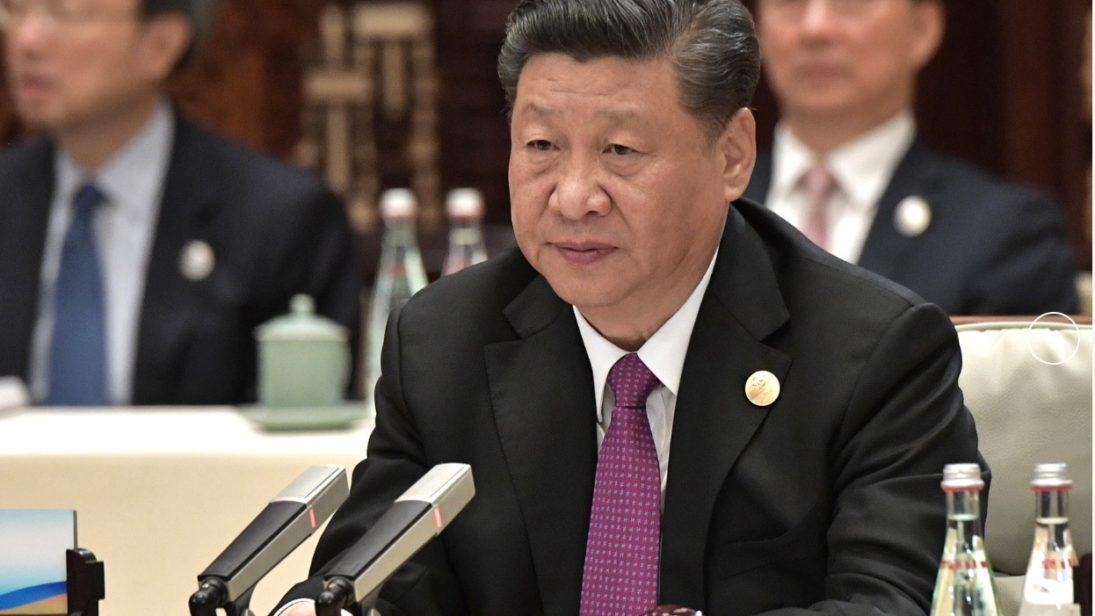

Image 1: The Kremlin