During an official visit to Kazakhstan on September 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping laid out his vision for what eventually became known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This multi-decade global infrastructure plan spans 70 countries, stretching from East Asia through Europe. Its reported price tag is over USD $1 trillion; some estimate it to be far higher than that number.

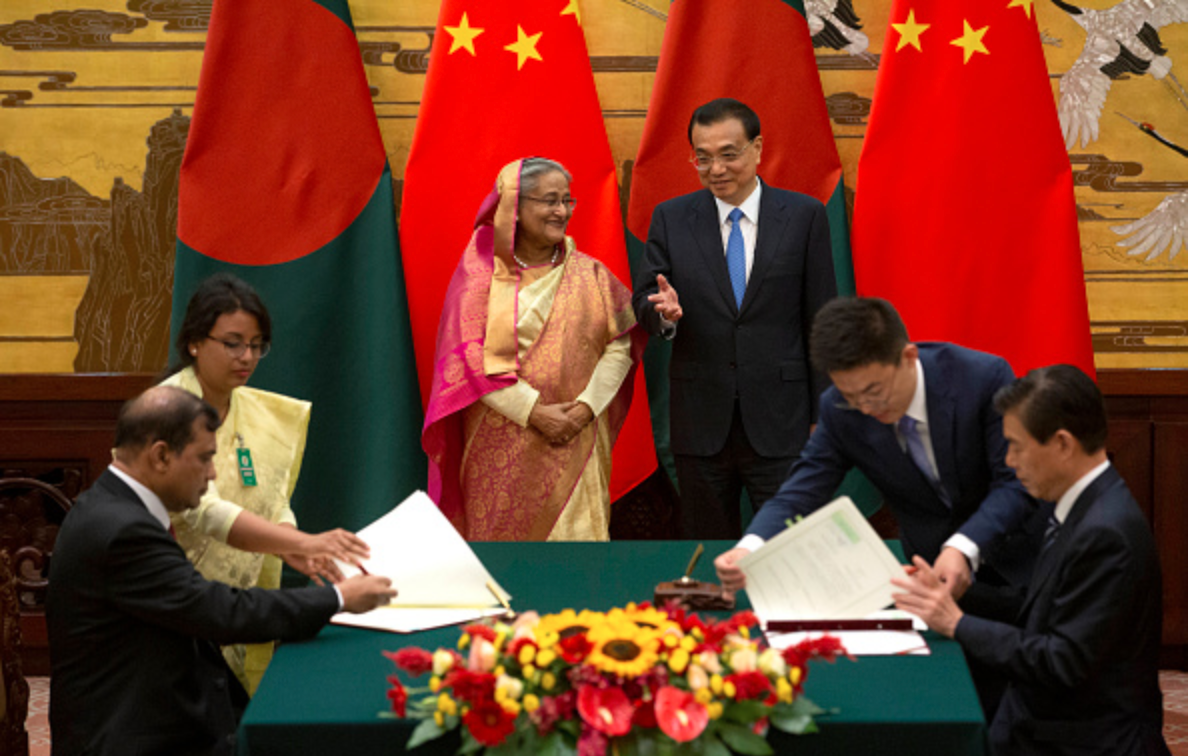

Bangladesh officially joined the BRI during Xi’s October 2016 visit to Dhaka—elevating the Sino-Bangla relationship to a “strategic partnership.” Both countries also signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for projects worth over USD $25 billion. Initially, Bangladesh was slated to be part of the Bangladesh China India Myanmar (BCIM) Economic Corridor, a 2,800 km project aiming to connect Kunming in China to Kolkata in India, via Bangladesh and Myanmar. However, as India expressed its unwillingness to be a part of BRI, the BCIM corridor was not included in the list of projects at the end of China’s high profile Second Belt and Road Forum. Multiple heads of states attended this second forum and signed infrastructure deals worth billions.

Despite these apparent setbacks, in a July 2019 visit to Beijing Bangladeshi Premier Sheikh Hasina and Xi reaffirmed interest in reviving the BCIM corridor. Even without an official BCIM corridor revival, China has carried out significant development projects in Bangladesh. Bangladesh has had a longstanding diplomatic relationship with India, one that China’s increased influence in Bangladesh is likely to sour. As India competes with China for influence in South Asia, it may interpret Chinese involvement in Bangladesh as encroachment on India’s sphere of influence. In such a scenario, Bangladesh must walk a tightrope where it maximizes benefits from Chinese infrastructure projects and limits Chinese involvement in historically contentious matters with India, including water-sharing.

A look at the numbers

Bangladesh must walk a tightrope where it maximizes benefits from Chinese infrastructure projects and limits Chinese involvement in historically contentious matters with India, including water-sharing.

During Fiscal Year (FY) 2017-2018 and FY 2018-2019, Bangladesh Bank data shows that China was Bangladesh’s top source for foreign direct investment at USD $506 million and USD $1.6 billion respectively, with the majority invested in Bangladesh’s energy sector. Data from Bangladesh’s Economic Relations Division, updated through June 2019, shows that a number of projects have already seen noteworthy disbursement of funds.

Since 2016, China has committed loans close to USD $1.4 billion, at two percent interest, with grace periods ranging between four and six years, accompanied by repayment periods ranging between 12 and 20 years. Projects under these terms have seen disbursement of around USD $879 million. Disbursement of Chinese supplier’s credit data has been around USD $534 million, compared to a total loan amount of USD $2.7 billion. Details for higher interest loan projects are scarce but it appears these loans amount to less than USD $35 million.

China’s mammoth investments in Bangladesh shake up the established geopolitical tea leaves in the region. These investments—and rhetoric about a more strategic partnership— threaten India’s position as Bangladesh’s preeminent ally and partner. Examples of predatory Chinese debt trap diplomacy—including Hambantota in Sri Lanka—has given Dhaka some pause as it fears the risks of going all in on Beijing’s column. China has thus far contributed less in development aid than the International Development Association (IDA), Asian Development Bank (ADB), and Japan, who together committed close to 70 percent of the USD $25.2 billion to Bangladesh between 2016 and 2018. Japan and Bangladesh share an especially long history of cooperation, reflected in the fact that the top 10 sponsored projects in Bangladesh are backed primarily by Japan.

Soured ties with India lead to a shift to China

As the Sino-Bangla relationship has become more robust and far-reaching—mirrored especially in increased defense ties—it is poised to cast a shadow over Bangladesh’s more established relationship with India. This a bond formally began with the signing of the Indo-Bangladesh Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Peace on March 1972. Since then, India and Bangladesh have signed a litany of bilateral agreements, including an historic enclave swap agreement, and a deal granting India shipping lines transit at no cost through Bangladesh. India has not been able to compete with the billions China has more recently poured into Dhaka.

Billions in Chinese investment have come as the Indo-Bangla relationship has soured over the passage of India’s Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Thousands in Bangladesh protested the controversial law, perceived as anti-Muslim and harshly punitive toward Bengalis.

This comes as the Indo-Bangla relationship has soured over the passage of India’s Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Thousands in Bangladesh protested the controversial law, perceived as anti-Muslim and harshly punitive toward Bengalis. Comments from Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) Home Minister Amit Shah referring to “infiltrators from Bangladesh” as termites have added fuel to the fire, and raised questions about an Indo-Bangladesh relationship in crisis. High-level delegations from Bangladesh canceled trips to India amid CAA protests, and reports also emerged that India’s High Commissioner to Bangladesh could not secure a meeting with Hasina. A sudden visit from Indian Foreign Secretary Harsh Shringla did not appear to deter Bangladesh green lighting Chinese company Sinovac to carry out trials of its COVID-19 vaccine in Bangladesh.

Indo-Bangla discord may help explain China’s increased investment in Bangladesh. Recently, China offered to assist Bangladesh in dredging and embanking large portions of the Teesta river, a vital water and livelihood source for millions of Bangladeshis and Indians. Bangladesh and India failed to reach a water-sharing agreement over the Teesta river, leading Bangladesh to receive less and less water during the dry season, adversely affecting the millions who depend on the river. China’s offer, should Dhaka accept it, will likely deepen a rift between Dhaka and New Delhi. If Bangladesh were to take China up on this offer, it would mark a shift in the traditional dynamics of the Indo-Bangla relationship. A relationship historically based in based finding common ground and avoiding conflict would see a more assertive Dhaka pairing with China to achieve its interests.

To this effect, Bangladesh has requested USD $6.4 billion from China for critical infrastructure projects such as the Payra Sea Port, the expansion of the Sylhet Airport, establishing power grids, modernizing telecom networks and IT infrastructure. Some have discussed the possibility of a rail link with China. Further, China granted duty free access to 8,256 Bangladeshi products in the Chinese market. Bangladesh’s willingness to work with China despite its history of debt-trap diplomacy could significantly hamstring India’s position in Bangladesh.

Moving forward

Despite these shifts, Bangladesh and India retain important bilateral ties, rooted deep in a shared history stemming from the British colonial era. Both navies carried out joint-naval exercises in the Bay of Bengal. India is one of Bangladesh’s biggest trade partners providing favorable terms for loans along with US$2 billion line of credit. Bangladesh is also likely to import millions of COVID-19 vaccine doses manufactured in India.

There are historical and cultural barriers Bangladesh faces with China that it does not, largely, with India. China’s veto on Bangladesh’s entry into the UN and its treatment of majority Muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang anger many in Dhaka. Bollywood films and West Bengali television dominate Bangladesh’s cultural zeitgeist. It is difficult for China to access this cultural landscape due to linguistic differences. Also, in a recent gaffe, the Chinese Embassy sent a gift to opposition leader Khaleda Zia on August 15, her supposed birthday, which also happens to be Bangladesh’s National Day of Mourning, commemorating the day when Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujib, was assassinated. Despite these gaffes, Bangladesh may very well continue working with China, BRI or not. Bangladesh’s infrastructure needs are immense and a partnership with China could readily become a vehicle for Bangladesh to reassert itself vis-a-vis India. As these projects shake out and the eventual repayment date nears, we will have a better sense of how the tea leaves are playing out.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of the SAV series “Instruments of Influence? Chinese Financing in South Asia,” which analyzes the impact of China’s loans, investments, and financing on domestic politics and geopolitical dynamics in South Asia. The full series can be read here.

Views expressed here are the author’s own and should not be attributed to any organization with which he is affiliated.

***

Image 1: Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: Mark Schiefelbein via Getty Images