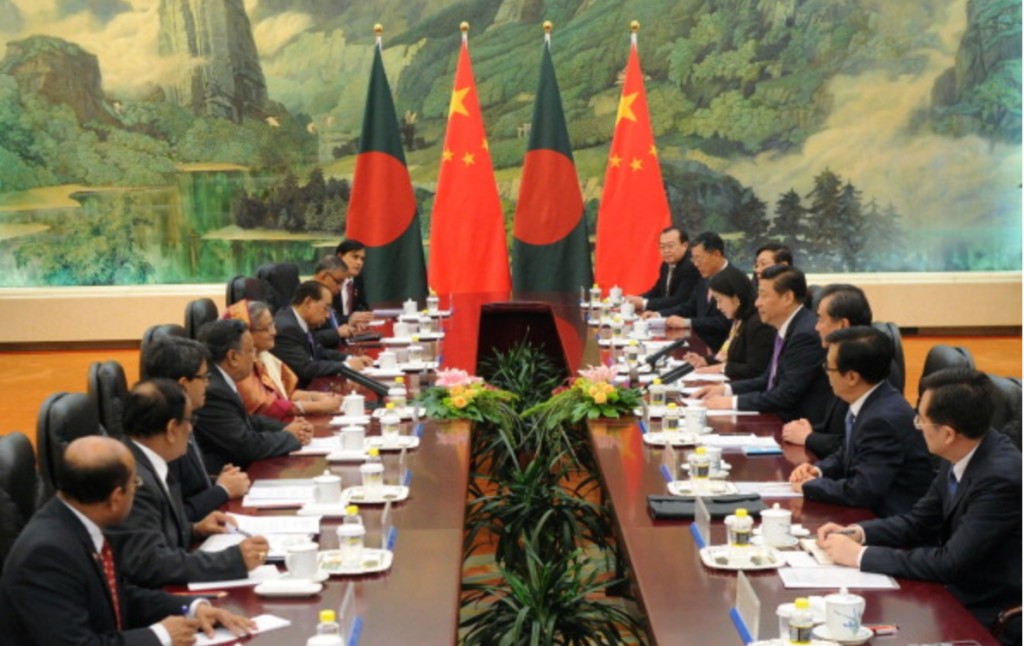

The China-Bangladesh relationship has enjoyed a growing closeness in recent years, particularly after Xi Jinping’s 2016 visit to Bangladesh – the first by a Chinese premiere since 1986. Historically, China was a key ally of Pakistan during the 1971 Pakistan-Bangladesh war, and China-Bangladesh relations continued to be rocky until 1974 as China vetoed Bangladesh’s United Nations membership. However, as the People’s Republic of China gained global recognition, diplomatic ties were finally established in 1976. Since then, Dhaka and Beijing have extended their initial cooperation in trade and defense to collaborate in the political, social, cultural, and maritime spheres–today, China is Bangladesh’s largest trading partner, with annual bilateral trade exceeding USD $12 billion.

Bangladesh’s association with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) since 2016 has considerably accelerated this cooperation, symbolized by Bangladesh’s presence at the BRI Forum this past week, with a 37-member delegation, led by Industries Minister Nurul Majid Mahmud Humayun. While Chinese motives behind BRI projects have come under criticism in recent years, Bangladesh, unlike many other BRI member states, has for the most part been successful in navigating these concerns—it has diligently chosen projects that fund its developmental growth while elegantly balancing the interests of regional superpowers. As new interests emerge, Bangladesh needs to maintain this position, focusing on the economic merits of the projects and steering clear of the geopolitical tussle.

China’s Economic Footprint in Bangladesh

While Chinese motives behind BRI projects have come under criticism in recent years, Bangladesh, unlike many other BRI member states, has for the most part been successful in navigating these concerns—it has diligently chosen projects that fund its developmental growth while elegantly balancing the interests of regional superpowers.

China has pledged almost USD $38 billion in aid, loans, and other assistance to Bangladesh, which includes infrastructure projects and joint venture initiatives. BRI investment is spread across multiple sectors driving Bangladesh’s rapid gross domestic product (GDP) growth, including infrastructure, connectivity, and shipping. While pre-BRI investment was largely limited to bilateral trade and private sector investments, BRI opened doors for a wider array of involvement, especially in infrastructure. For example, projects such as the Karnaphuli Tunnel and Special Economic Zones such as in Chittagong—which were previously negotiated independently—have been incorporated under BRI.

Moreover, in 2018, China agreed to provide USD $3.14 billion in loans for the ambitious USD $3.7 billion Padma bridge—the largest infrastructure project undertaken in Bangladesh’s history. More recently, a consortium of the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges bought a 25 percent stake in the Dhaka Stock exchange, outbidding India by 56 percent. In the power and energy sectors, Bangladesh signed USD $4.5 billion worth of deals during Xi’s visit in 2016.

In terms of port investment, though China failed to secure the development of the Sonadia deep-sea port—widely believed to be the result of political pressure from India and the United States—it secured partial investments in the Payra and Chittagong seaports. In addition, Chinese firms are developing Bangladesh’s largest economic zone and China’s foreign direct investment inflows to the country increased to USD $506.13 million in 2017-18, outpacing the United States.

Thus, Bangladesh holds an important position not only in BRI’s overall strategy but also in China’s efforts to diversify investments globally. With China’s soaring costs and cooling economic growth, Bangladesh provides both cheap labor and high growth potential. Geographically, Bangladesh’s geographic location in the Bay of Bengal can be key for a China that is looking to reduce its over-reliance on energy imported from the Middle East through the Malacca Strait.

TakingStock: Dhaka’s Concerns Over Chinese Investment

However, given China’s dubious, opaque excursions in other countries, questions have aptly arisen on whether these investments may be a ploy to entangle Bangladesh in a debt trap, aiding China in establishing regional hegemony in South Asia. These concerns are largely driven by examples of Bangladesh’s neighbors. In a nearby BRI project, Sri Lanka was forced to hand over Hambantota port to a Chinese company for 99 years after failing to pay back construction loans. Avoiding such financial risk, Malaysia rejected a Chinese-financed infrastructure project worth USD $20 billion, while Sierra Leone canceled plans to seek Chinese funding for an airport. Myanmar too scaled back Chinese loans for some of its projects, while even Pakistan, China’s greatest ally in the region, has turned down funding for some of its own power and infrastructure projects.

While these decisions were mostly driven by economic calculations, they were also made out of strategic concerns. But for Bangladesh, such concerns about entrapment are yet to be perceived as problematic since the government has shown astuteness in choosing which funds it will take. A key recipient of bilateral and multilateral funds such as through the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the United States Agency for International Development, and the Japan International Cooperation Agency, Bangladesh has ample experience in selecting the right type and quality of international funding. In fact, Bangladesh’s national external debt stands at 14.3 percent of GDP, which officials believe is under control. Thus, being a seasoned actor in utilizing international aid and loans has helped Bangladesh in its assessment of BRI projects.

Bangladesh has already shown that if a Chinese project lacks economic or political sense, the government would not hesitate to refuse assistance. In addition to the cancellation of the Sonadia deep-sea port, Dhaka turned down Chinese loans last year for the construction of a highway over an inflated price tag and allegations of corruption, instead choosing to finance it through its own coffers. In a recent statement, State Minister for Foreign Affairs Shahriar Alam emphasized that Bangladesh is seeking alternative sources to finance future development, underscoring that the government is simultaneously working to reduce its reliance on BRI funding.

Bangladesh’sBalancing Act: Engaging Regional Powers

Bangladesh hopes to become a middle-income country by 2021, which will require annual investment of over USD $24 billion. Therefore, for many in Bangladesh, appropriate funding is welcome, wherever it is from.

Bangladesh has already shown that if a Chinese project lacks economic or political sense, the government would not hesitate to refuse assistance. In addition to the cancellation of the Sonadia deep-sea port, Dhaka turned down Chinese loans last year for the construction of a highway over an inflated price tag and allegations of corruption, instead choosing to finance it through its own coffers.

In this context, Dhaka’s balancing act between economic powers in the region merits recognition. So far, Dhaka has done a decent job of keeping regional powers satisfied by allocating projects effectively. Alongside China, India has been the most influential in vying for a share of Bangladesh’s economic landscape. During Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s visit to India in 2017, India pledged USD $4.5 billion in loans for infrastructure and power sector projects. While China already has significant investment in the country’s power sector, India has upped its stakes recently, committing almost USD $10 billion worth of investments. China is Bangladesh’s largest supplier of arms equipment but India has in response tried to increase its intervention by providing a USD $500 million line of credit for the purchase of defense equipment.

Interestingly, Bangladesh has not conceded financing of any of its ports to a single country, with India, China, and Japan jointly investing in the Payra port. A recurring feature of many of its projects, Bangladesh divided the development of the port into 19 components, opting for separate funding strategies for each component that ranges from government to government cooperation to public private partnership. Japan has historically been a key partner for Bangladesh, and it too has recently increased support and is expected to provide its largest ever loan to Bangladesh for power, port, transport, and infrastructure projects.

Finally, the United States has historically been the largest source of FDI in the country, until China toppled it last year. The recent Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy, widely touted as the United States’ counterbalance to BRI, is an exciting prospect for Bangladesh. While still a vague concept and in a nascent stage (mostly geopolitical and security-based), Bangladesh should take interest in its economic potential, similar to its positioning towards BRI. The United States has already allocated USD $40 million towards Bangladesh’s maritime security, humanitarian assistance and disaster response, peacekeeping, and capabilities to counter transnational crime. Beyond these areas, Bangladesh is holding out for more information on FOIP’s concrete strategic direction before determining a fixed path for Bangladesh’s engagement with either BRI or FOIP. However, given the scope of funding and opportunities for development, it is possible and advantageous for Bangladesh if both BRI and FOIP operate in tandem.

BRI projects in developing countries—and their underlying intentions—have been rightly put under great scrutiny. For Bangladesh, BRI funds have been more a blessing than a curse, as the country searches for investments to feed its target of eight percent GDP growth. Rather than looking at the BRI as a whole, Bangladesh has focused on individual projects. Success in navigating emerging geopolitical tensions will not only require maintaining this position, but also keeping an eye towards protecting Bangladesh’s autonomy, be it BRI or FOIP.

Editor’s note: With the second edition of the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation being held recently, all eyes were on whether China had learnt any lessons from implementing the project for five years and how it would adjust its plans to address member states’ concerns. But what have the smaller states in South Asia such as Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh learnt from their experience with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)? How has their engagement with BRI evolved over time and where is it headed in the future? These are some of the questions that this series explores, which can be read in full here.

***

Image 1: Russell Watkins/UK Department for International Development via Flickr

Image 2: Wang Zhao/Pool via Getty Images