Nepal’s tumultuous political transition came to an end with the promulgation of a new constitution in 2015, followed by elections that transformed the country from a monarchy to a federal structure with a stable government at the center. There remain high hopes and expectations among the Nepali public that the new government will be a harbinger for peace, economic development, and prosperity. To make these dreams a reality, Nepal requires investment in infrastructure development, as well as the establishment of industries that might create employment opportunities. As internal resources are insufficient to fulfill people’s quest for economic development, Nepal is looking for foreign investment mainly from its immediate neighbors, India and China.

Yet rivalry between India and China has been a stumbling block to Nepal’s successful development of late, as competition between the two Asian giants has stalled or prevented large infrastructure projects from coming into fruition. However, in a hopeful proposal from Beijing at the informal Wuhan summit earlier this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping reportedly suggested to Prime Minister Narendra Modi that India and China should hold trilateral talks with smaller South Asian countries like Nepal in a “two plus one” dialogue mechanism. Bearing its development aspirations in mind, what should Nepal make of this 2+1 dialogue proposal?

Indo-Chinese Competition in Nepal: Obstacle to Development

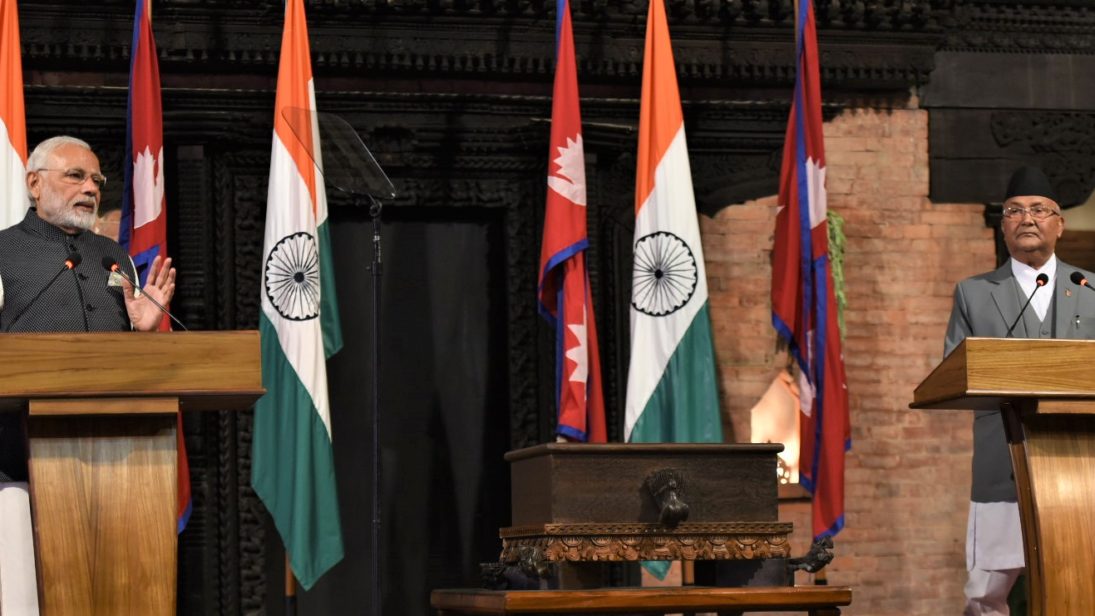

While India and China seem to be increasing their status at the global level, Nepal is seeking to establish itself as a developing country, with aspirations of becoming a middle-income country by 2030. For Nepal, China and India, its only neighbors and two of the world’s burgeoning economic powerhouses, are natural partners for investment. Addressing a program organized by Nepal-China Business Forum in June this year, Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli said, “Investors always look for market, which is not a problem in Nepal. As you all know, Nepal is located between two vibrant markets of the world, India and China with a population of over 2.5 billion. Production is the only problem. Our productive capacity is limited.” Beijing has abundant capital as well as technology, while India has a market that is easily accessible for Nepal.

Both India and China have long maintained a footprint in Nepal. However, with its flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Beijing has recently sought to deepen its presence in the country, to the dismay of New Delhi. The need for a 2+1 dialogue mechanism between India, China, and Nepal thus becomes clear when one considers how geostrategic competition between the two giants in the country has played out to the detriment of Kathmandu. For instance, the 750-megawatt West Seti hydropower project in Nepal has been victim to this rivalry. In August, news outlets reported that a subsidiary of China’s Three Gorges Cooperation found its 2012 agreement to develop the West Seti hydropower project to be financially unfeasible due to steep resettlement and rehabilitation costs. This eventually led to Nepal cancelling its agreement with Beijing on the construction of the $1.6 billion USD hydropower project. However, some media reports suggest that China cancelled the West Seti project after it did not see the economic viability of projects. This was related to India’s refusal to purchase the electricity produced by a Chinese company: in 2016, India introduced a regulation that states that India will purchase electricity only from those companies that have a 51 percent equity investment of Indian public and private companies. In other words, India—Nepal’s largest market for the sale of hydropower—is unwilling to buy electricity produced by a Chinese company, which means that Chinese companies are reluctant to invest in hydropower projects in Nepal.

Beijing’s BRI is another issue on which India has expressed its reluctance. In a private conversation, Nepali ruling party leaders confess that there is pressure from India when it comes to BRI projects. India has refused to endorse China’s BRI, and is likely trying to convince leaders in Kathmandu that BRI projects are not good for Nepal as they are likely to invite debt problems. Nepal, however, signed a framework agreement on BRI in May 2017. Nevertheless, these mega projects might continue more smoothly if there is further consultation and understanding between India and China.

From Trilateral Cooperation to the 2+1

China devised the 2+1 dialogue concept after Chinese and Nepali officials and think tanks had advanced the idea of “trilateral cooperation” between India, China, and Nepal without any formal initiative coming to bear. A senior Nepali politician and former prime minister, Pushpa Kamal Dahal, had even raised the point of “trilateral cooperation” with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping during the BRICS Summit held in Goa in October 2016. At the time, he said that both the Chinese and Indian leaders responded “very positively” to the prospect of trilateral cooperation. India, however, was quick to say that meeting among top leaders was not a trilateral meeting.

In Nepal, the proposed 2+1 concept could ease tensions between India and China in Nepal, as it would provide the platform to reach an understanding on the sale of hydropower electricity and BRI, outline the path forward for Chinese investments in the country, and create an environment of mutual trust.

In Nepal, the proposed 2+1 concept could ease tensions between India and China, as it would provide the platform to reach an understanding on the sale of hydropower electricity and BRI, outline the path forward for Chinese investments in the country, and create an environment of mutual trust. This is even more significant to Kathmandu due to shortfalls in Indian investment in recent years; Nepali businessmen say that investment from India has not been per Nepal’s expectations. In an interview with Press Trust of India in March this year, SAARC CII President Suraj Vaidya, a renowned businessmen in Nepal said, “So if no Indian investment is coming to Nepal, we have to look for other investment…[China is] bound to become the largest investor in the world.” According to him, there have been few large Indian investors since the mid-1980s. With the India-Nepal trade deficit tilted in India’s favor, a lack of movement on decades-old India-Nepal infrastructure projects, and Indian companies’ reticence to invest in Nepal, investment from Beijing is of the most importance to Nepal’s development—as is India’s comfort with Chinese investment. If there is understanding between the two countries via the 2+1 dialogue mechanism, India will likely be less suspicious of Chinese investment in Nepal; it may even decide to collaborate with China to invest more heavily in its neighbor. This will, ultimately, prove indispensable to Nepal’s development aspirations in the long run.

Implementing the 2+1 Mechanism

Undue pressure from India on China-funded projects will likely continue to delay or stall projects in Nepal. It would be better if Nepali leaders could attempt to bring India into a 2+1 model behind closed doors.

The implementation of the 2+1 model will not be an easy process. Despite the recent thaw between India and China, India views Nepal as its exclusive zone of influence; it remains challenging to convince New Delhi to join hands with Beijing. On the other hand, Nepal itself appears perplexed by this model. Neither the government nor politicians have publicly spoken about the proposal forwarded by China. This is perhaps because the incumbent Nepali government is walking a tightrope to maintain a balance between the two rivals. However, undue pressure from India on China-funded projects will likely continue to delay or stall projects in Nepal. It would be better if Nepali leaders could attempt to bring India into a 2+1 model behind closed doors.

If there is not a sort of understanding between three countries, the current scenario will only persist. In an interview with Kantipur Daily, Hu Shisheng, director of the Institute of South and Southeast Asian and Oceanian Studies at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, said that if India does not agree to the 2+1 model, “China and India will move ahead according to their own plan.” In other words, if India will not acquiesce to a 2+1 dialogue mechanism, the ongoing geostrategic competition in Nepal may only worsen, stymieing the country’s hopes for a brighter future.

***

Image 1: MEAPhotogallery via Flickr (cropped)

Image 2: Wikimedia Commons