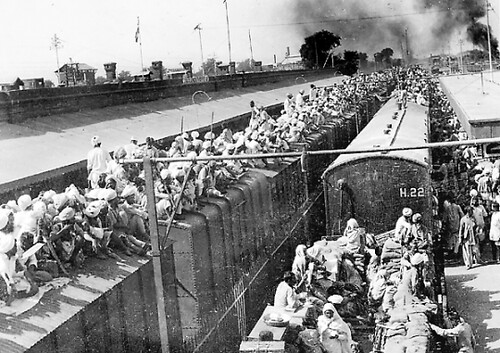

Away from the unfolding negotiations between departing colonial rulers and leaders of the newly independent states of India and Pakistan, the Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 ripped apart the inhabited worlds of millions. Violence and destruction swept large swathes of land, claiming an incalculable toll. For the most part, the millions who were compelled to migrate, were clueless about what lay ahead, for in one stroke, they had been rendered stateless and rootless. “Everybody was looking for a safe refuge for his or her person, family, and belongings.” Some took trains to travel to the other side, while others hit the road, climbed on already overflowing military trucks, or simply walked on foot to escape the raging violence and reach their new countries of residence. This journey did not end once they crossed the border; it only gave way to another tortuous journey of resettling, re-establishing themselves in new surroundings, and rebuilding their upended lives.

The Partition continues to reverberate till today, framing and reframing the lived present. Its legacies shape personal, collective, social, and political memories in the subcontinent. They modulate relations between individuals, communities, and nations. Without adequate space for memorialization, the enduring sense of loss and anguish caused by the Partition can sustain intergenerational trauma. Further, it can breed interreligious hatred and violence. It is for this reason that the struggles of people and communities who walked through these raging fires demand conscious acknowledgment from those of us who came after.

Recollections and Recapitulations of Partition

The accounts of Partition survivors poignantly delineate a rupturing of their lived and familiar. In their oral narratives, the “before” and “after” of Partition are often represented as two different worlds altogether. In my grandmother’s stories for instance, Partition is related as a tragedy that reordered her family’s fortunes, and irrevocably changed their lives. She often reconstructs her family’s arduous journey across the newly created national border to the Indian side of Punjab, and subsequently to Rajasthan. They moved amidst harrowing circumstances, facing food and water shortages, threats of contracting diseases, and the likelihood of attacks by roving bands of rioters. As a child, I grew up ingesting these stories of the Partition, which seemed both near and distant, remote yet resonant. Ensconced in my comfortable middle-class surroundings in a city in central India, I tried to imagine what it would be like to abandon one’s home to board a train headed towards an unknown, unfamiliar destination, leaving everything behind, hearing the wildest of rumors, witnessing scenes of horrific violence, and staring at an acutely uncertain future.

The Partition continues to reverberate till today, framing and reframing the lived present. Its legacies shape personal, collective, social, and political memories in the subcontinent.

Partition in Past and Present

The Partition of the subcontinent refuses to recede into the distant past: it is recollected and spoken of not as a long-gone forgotten event, but as a watershed moment that continues to inflect present realities in multiple ways. It has reconfigured the existence of different communities across time and space, and over succeeding generations. Over time, people have evolved their own means and methods to record the moment of Partition, often by transmitting their memories to those who came after. Stories narrated by grandparents and family elders, the practice of naming commercial establishments out of a nostalgic longing for a lost homeland (vatan), and countless portrayals of the Partition in art, literature, theatre, cinema, and a range of other genres represent only a few attempts at memorialization.

However, along with attempts to preserve its memories, the states affected by Partition have also tapped into this moment for their own political gains. Leaders of these states have selectively invoked Partition memories to tighten the existing security net, instill fears, deepen discord, and progressively enlarge an already sizeable military apparatus. Repeated confrontations between Hindus and Muslims across South Asia have been framed as a sequel to Partition. These confrontations are presented as fitting occasions for exacting revenge and retribution on the “other”, for Partition’s unhealed wounds. Advocates of a Hindu Rashtra (Nation) in India perpetuate the vengeful discourse that Indian Muslims are the archenemies of the Hindu community andcite the partitioning of the Bharat Mata (Mother India) as the ultimate proof of their perfidy. Militant Hindu organizations have castigated Indian Muslims for their supposed extra-national loyalties and affinities to Pakistan. To fuel this charge, they have labeled Muslim-majority neighborhoods across many cities in India as mini Pakistans.

Its resounding reverberations modulate the construction of present-day identities, often influencing how communities draw boundaries, seek to imagine themselves, and perceive their supposed “others”. It is “an event of the past and simultaneously a sign of the present.”

Engaging with Traumatic Memories

For many in the subcontinent, stories of the Partition are integral to their personal and collective psyches. They work at different levels, shaping the social and political, the real and symbolic. The memories and narratives of Partition require sensitive engagement but finding the appropriate space for this is not easy. Attempts to suppress past violence and trauma may seem to work on the surface, yet without avenues for acknowledgement and expression, their memories continue to fester and prolong a sense of hurt. The scars of Partition still breed hate and hostility. They have created arrogant, vengeful majorities and besieged, mistrusted minorities. The memories of those fateful days cannot be simply wished away or effaced; they need to be retrieved from the steadily gathering dust of time.

It is this gap that initiatives like The 1947 Partition Archive, based in California in the United States, try to bridge. The online archive has recorded and stored a vast reserve of oral history interviews conducted with those who lived through and experienced Partition. It has built a rich repository of personal narratives and remembrances collected from resident and diasporic communities of three South Asian nations: Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. The oral history collections at the archive seek to map the immediate experience of Partition, how it shaped the everyday for myriad uprooted individuals, families, and communities, and the ways in which they engaged with their past to (re)configure a present and future for themselves.

Working as a researcher at the Partition Archive in 2021, I encountered numerous stories of loss, despair, and violent dislocation. However, these stories also contained distinct undertones of exceptional human courage and endurance. Amidst everyday horrors and suffering, people plodded on and journeyed across emerging borders. Cutting across differing ages, communities, religions, and newly divided nationalities, their common indomitable fighting spirit stood out.

What people and communities touched by the Partition can accomplish, 75 years on, is to stitch together many more restorative efforts like the easy-to-access digital Partition Archive.

Recovery and dissemination of stories from Partition hold important lessons. These stories can reshape historical memory and offer a new lens with which to look at South Asia’s history, geography, and politics.. However, we cannot let this lens be colored by prejudices, prefigured notions, and (in)visible communal hostilities.

What people and communities touched by the Partition can accomplish, 75 years on, is to stitch together many more restorative efforts like the easy-to-access digital Partition Archive. We must invest attention into conceptualizing such memory projects and other creative attempts that rope in diverse concerned individuals—students, researchers, artists, and activists interested in retrieving partitioned voices from different settings and locales across South Asia. We need to build a compassionate connecting bridge through time that, while acknowledging the interminable human suffering brought on by the Partition, widens the space for recovery and rapprochement.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: Saktishree DM via Flickr

Image 2: Saktishree DM via Flickr