After the initiation of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, South Asia has often been described as the linchpin of connectivity amongst BRI-participating nations. This is because economically, South Asia provides one of the world’s fastest developing markets. Geographically, it is at the crux of China’s resource needs. Politically, South Asian countries are increasingly gaining importance in Beijing’s geostrategic calculus.

Given Beijing’s rhetoric on BRI in South Asia, it is important to ask whether the foundations of this project in South Asia, specifically the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor for Regional Cooperation (BCIM) and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), actually amount to “win-win cooperation,” as China often claims? This piece argues that China can indeed become an active contributor to South Asian industrialization and development. China and South Asia’s mutually complementary industrial environments set the foundation for such a future.

Industrialization As a Space for Investment

Industrial investment is a major area for increasing China-South Asian cooperation. The World Bank’s Competitive Industrial Performance Index (CIP) clearly illustrates that baring India, South Asia has a sluggish pace of industrialization.

In contrast, China’s economic problems stem less from lagging industrialization and more from excess capacity in its manufacturing sector. Taking steel capacity as an example, in 2017, China wasted over 325 million tons of steel production. In his 2016 Report on the Work of Government, Chinese premier Li Keqiang identified overcapacity as one of several economic bottlenecks in contemporary China.

There is, therefore, a potential for China’s economic overcapacity to complement South Asia’s slow industrialization, which could be effectively unlocked by China’s growing investments. To this end, Beijing hopes to encourage industrial capacity relocation and infrastructure investment through BRI. This kind of cooperation is mutually beneficial, as exemplified by CPEC, which contributed 20.9 percent to Pakistan’s GDP in 2016-17, creating 30,000 jobs between 2015 and 2017. It is projected to create upwards of 700,000 jobs in Pakistan within the next thirty years. A recent report from the ILO International Labor Organization (ILO) also estimates CPEC will generate 1 million jobs within Pakistan.

What About India?

India has traditionally been BRI’s most wary observer, but as South Asia’s regional leader, it is also the nation to which China must pay the most attention. Previously, India has supported several regional cooperation regimes that under-emphasize China, like the Modi government’s 2014 Project Mausam (PM) , which along with the 2015 “Cotton Route” has been regarded as India’s answer to BRI. While neither of these projects turned out to be economically viable, they demonstrate India’s perceived need for creating competing institutions to BRI.

However, India’s inefficiency in promoting regional economic development has eroded its leadership. Economically, intra-regional cooperation currently constitutes only a limited contribution to South Asia’s economic development at only 5 percent contribution to regional total trade and less than 1 percent contribution to the whole region’s overall investment. Cooperating regimes, the South Asia Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), the SAARC Preferential Trading Arrangement (SAPTA), and the South Asian Free Trade Area Agreement (SAFTA), only achieve minimal gains because of India’s highly politicized economic relations with its neighbors. For example, in 2016, the Chair of SAARC, Nepal, canceled SAARC’s regular summit after India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Afghanistan refused to attend the event planned to be held in Islamabad.

In spite of its suspicion, India still has strong incentives to participate in BCIM, Economically, BCIM’s planned “Kolkata to Kunming” route will provide an opportunity for all four BCIM countries to exploit trade complementarities. Furthermore, analysts argue that BCIM provides economic and political benefits to India’s underdeveloped northeastern regions, which have been a source of concern after India’s largely ineffective 1987 Border Areas Development Program.

Addressing Additional Concerns

Besides India, many countries worry about China’s so-called “debt trap diplomacy,” particularly after the Hambantota Port incident. However, these concerns fail to consider the 84 instances in the last 15 years where China reconstructed or waived loans without taking any assets. Among the twenty-two projects within CPEC, China only provides concessional loans for four programs. A 2017 IMF report shows the peak outflow of CPEC debt will be easily covered by Pakistan’s increasing exports, anticipated to reach $40 billion by 2024. For other countries, debts from BRI are also manageable. Myanmar, for instance, has slashed the price of a Chinese-led port project from $7.2 billion to $1.3 billion this year without Chinese repercussions. It has also publicly refuted debt trap in the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor.

Furthermore, CPEC demonstrates the non-exclusiveness of BRI. Chinese investors are required to follow universally applicable IPP policies, conforming to international norms. Furthermore, China consistently searches for multilateral cooperation to fund infrastructure investments. For example, Pakistan invited Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the United States to join CPEC projects. These efforts demonstrate China’s intention to construct CPEC as an open regime.

In short, although countries maintain legitimate suspicion over thenature of BRI loans, these suspicions are largely misplaced. Sri Lanka’sHambantota port incident is an exception, not the norm of Chinese loanstructures, and Beijing has little intention of politicizing its projects, elseit becomes no different than investment packages offered by the United Statesand other powers.

Contributor or Troublemaker?

Compared with other major powers, China’s projects uniquely integrate cooperative mechanisms with tangible economic benefits in South Asia. For example, U.S. investment in South Asia has been historically over-politicized, such as the New Silk Road Initiative in 2011, which aimed to bolster political stability in Central Asia, along with other initiatives to promote regional economic connectivity in South Asia in 2014. Unfortunately, none of these projects successfully materialized. Other actors like Japan only offer limited projects that do not meet China’s scope of investment. Thus, China holds a unique competitiveness for investment in South Asia. Through investments in industrialization and the facilitation of regional cooperation regimes, China has the potential to become a significant contributor to South Asia’s economic development. However, China needs to grapple with legitimate anxieties over BRI among South Asian countries, particularly regarding investment transparency and the social and environmental consequences of BRI projects. Initiating self-regulating policies that are limited to the economic arena is China’s best choice for becoming a contributor to South Asian regional development.

***

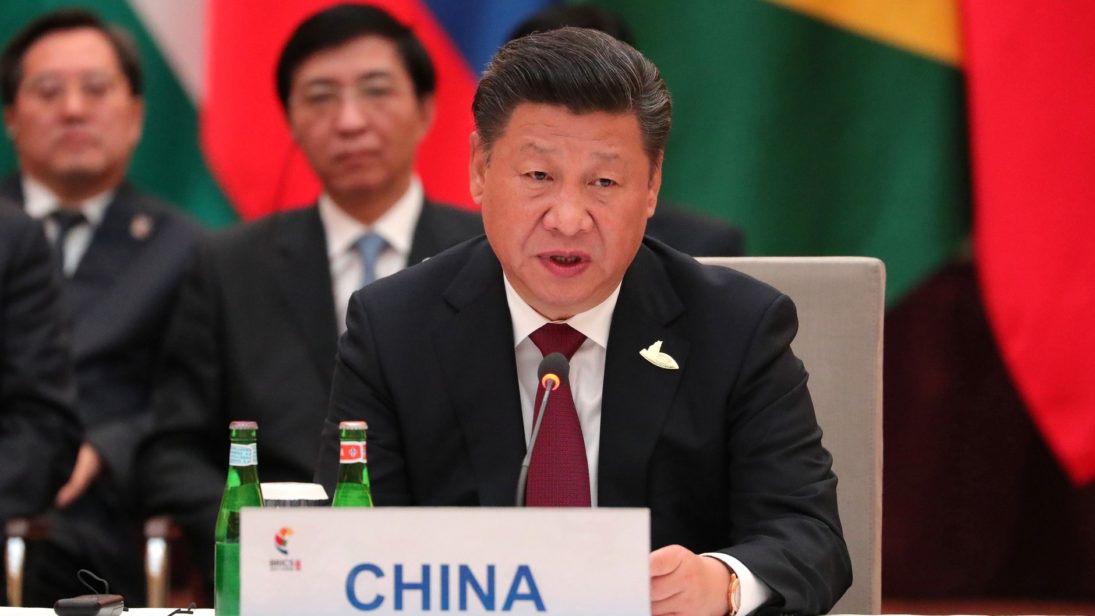

Image 1: The Kremlin via Wikimedia

Image 2: Atul Loke/Bloomberg via Getty Images