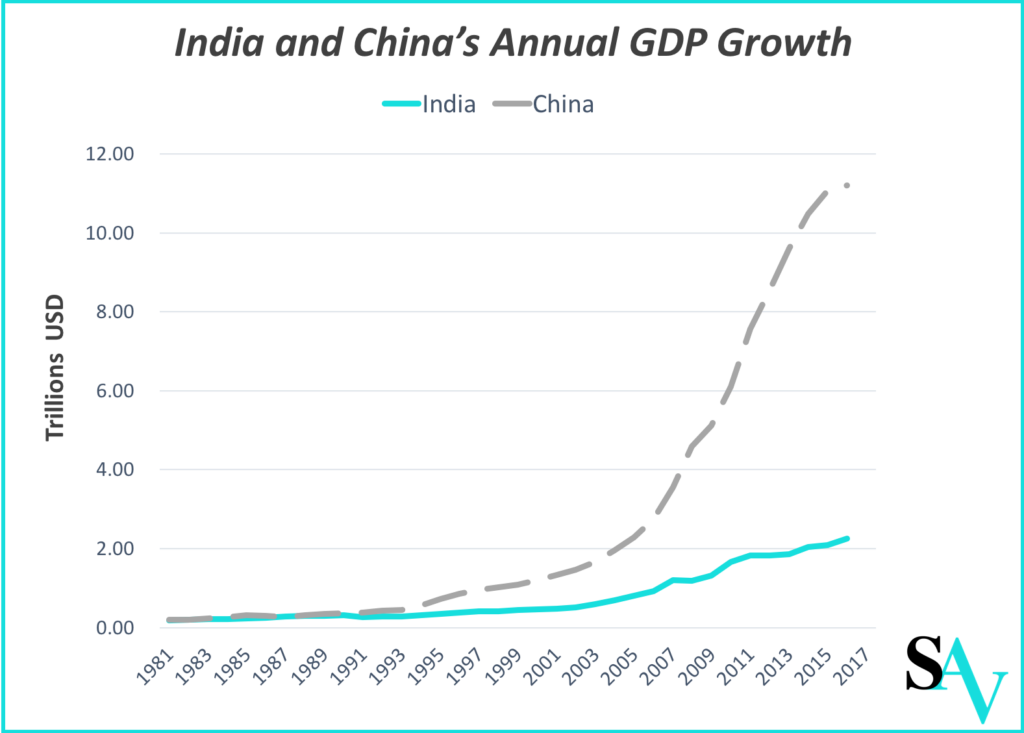

India has been one of the fastest growing economies in the world for over two decades. However, India’s economic performance in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) growth and macroeconomic stability is dwarfed by China’s. This disparity can be best illustrated by their respective economic trajectories: although they were of similar economic volume in the early ’90s, since then China’s gross domestic product (GDP) has strikingly grown to be almost five times bigger than India’s (see Figure 1). Given this, closer Sino-Indian cooperation may be a promising solution to some of India’s economic problems. To this end, instead of viewing India and China as the twin poster children of the emerging market on equal footing, policymakers in New Delhi should view China’s head start and India’s unrealized potential for growth as a conducive basis upon which to build the future of Sino-Indian economic cooperation.

Figure 1: India and China’s Annual Gross Domestic Product Growth, 1981-2017

Source: World Bank

Comparative Advantage and Economic Growth Trajectories

As economies with over one billion people, China and India share three important advantages: a large and low-cost labor force; a large domestic consumption market; and a wealth of high-quality human capital known for professional services and science and engineering talent.

Utilizing these three assets, China followed a three-step model. First, it focused on labor-intensive and export-oriented industries like apparel by tapping into its huge workforce. Then, with initial capital and expertise accumulated, it exploited growing domestic demand by initiating policies such as “market for technology,” through which Chinese companies traded access to the country’s markets for technology transfers. Following this, Beijing turned its attention to utilizing its large reservoir of talent by pursuing an innovation-driven development strategy. “Made in China 2025” was only one part of this process. It has been through this model that China has not only risen to boast the largest industrial output in the world but it also continues to march to the top of the global value chain.

Interestingly, with the same three advantages, India’s approach followed a reverse sequence: for decades, India has been famous for its highly-competitive technology- and capital-intensive industries like pharmaceutical and information technology (IT) services. While Indian manufacturing, such as cell phone and automobile part industries, have made major progress in recent years, they still lag behind in terms of international competitiveness. Diverging from the conventional growth pattern, India’s labor-intensive manufacturing sector is disproportionately underdeveloped, leaving its vast workforce largely employed in less productive informal sectors of the economy. Such a distorted industrial development practice has put a heavy toll on the Indian economy: the country is unable to meet its massive domestic demand for manufactured products such that Indian consumers have to rely on imported goods, and it fails to provide enough employment opportunities to cater to its ever-swelling ranks of job-seekers.

Industrialization Potential

The reason for China’s economic performance is massive industrialization: China has continuously reallocated large amounts of agricultural labor to more productive manufacturing sectors…India, despite its growth record, lags far behind in industrialization.

The reason for China’s economic performance is massive industrialization: China has continuously reallocated large amounts of agricultural labor to more productive manufacturing sectors. Beijing boasts a robust manufacturing sector, employing 29.3 percent of its labor force and comprising 39.5 percent of its economy. In comparison, India, despite its growth record, lags far behind in industrialization. Its agricultural sector makes up 16.8 percent of its economy but employs as much as 47 percent of its labor force, while the industrial sector makes up 28.9 percent of its economy while employing only 22 percent of the labor force. In this way, China and India’s contrasting approaches towards industrialization largely explain their diverging economic trajectories.

Although Indian decisionmakers have pursued industrialization, especially since Narendra Modi’s election as prime minister in 2014 and through the “Make in India” initiative, many of the major problems currently facing the Indian economy, such as its reliance on foreign capital inflows, the fragile falling value of the rupee, insufficient formal job creation, as well as the susceptibility of the agricultural sector to fickle monsoons, could be improved upon by making its industrial sector more competitive and materializing India’s vast potential for industrialization.

Can Sino-Indian Cooperation Make a Difference?

At this point, it is important to consider what role China could play to further India’s industrialization. As the only country in the region, if not the world, of a similar population size and development trajectory to India, China’s growth history can not only provide important lessons and experiences, but also critical material assistance in the form of direct investment.If China and India continue to build mutual trust and deepen cooperation to support India’s industrialization, they may achieve something far beyond their expectations.

So far, India’s cell phone industry is perhaps the best example. In 2017, India bypassed Vietnam as the world’s second largest cell phone producer by volume, occupying 11 percent of global production. To take advantage of the five percent tariff difference between a cell phone and its components (see Figure 2), Chinese companies began to export components to India and assemble them locally long before 2018. However, when India further increased customs duties on all electronics in April 2018, many major Chinese companies started relocating the entire cell phone production system to India, and encouraged affiliate suppliers to follow suit. Accordingly, though in the 2014-15 fiscal year, 78 percent of the cellphones sold in India were still imported as complete units, by 2017-18 that percentage dramatically reduced to 18 percent. This achievement was made possible by Chinese cell phone firms like Xiaomi, Vivo, Oppo, and Lenovo dominating the Indian market, with a combined market share of more than 50 percent.

With vertical supply chains and horizontal industrial clusters burgeoning in India, a robust cell phone production system is in the making, with the potential to cut local production costs dramatically. Once such a system is put in place, it can, in turn, attract more business along the same lines. Arguably, such a pattern may fare best in those industries in India that are local demand-driven, such as consumer electronics and engineering equipment manufacturing. This is largely because local demand for goods, combined with the Indian government’s protectionist tariffs and industrial policies, has made investing in local factories that produce such goods commercially viable.

The manufacturing of cell phones is just one example. If this pattern can be applied to other industries, not only will it offer India a large number of formal job opportunities, but it also will fundamentally strengthen India’s industrial base by bringing about self-reliant production ecosystems.

Conclusion

If China and India continue to build mutual trust and deepen cooperation to support India’s industrialization, they may achieve something far beyond their expectations.

For now, it would be best for Sino-Indian cooperation to be focused on labor-intensive and export-oriented industries, tapping into India’s abundant labor endowment. Considering both countries’ comparative advantages, such cooperation may well relieve India’s current trade deficit, and other persisting issues such as reliance on foreign capital and insufficient employment opportunities, while providing China with more avenues for growth. If industrialization is vital for India to become a global economic powerhouse, China can play a more active role. Fortunately, as revealed in the Xi-Modi Wuhan summit, both India and China now seem readier than ever to deepen bilateral cooperation in this aspect.

***

Image: MEAPhotogallery via Flickr