Last month, India held its premier foreign policy conference, the Raisina Dialogue on the sidelines of the G20 Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in New Delhi. As chair of the G20, New Delhi hosted formal negotiations among member countries, including an inconclusive meeting between United States Secretary of State Anthony Blinken and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. While the G20 meeting and Raisina Dialogue enabled India to draw attention to global issues such as food and energy security, it also highlighted India’s unique geopolitical position between the United States and Russia.

Despite India’s cordial relations with both the West and Russia, India did not leverage the conference as an ‘instrument of peace building’ to diffuse tensions between Russia and Ukraine. If India wishes to be a ‘first responder’ to international conflicts rather than a hesitant bystander, New Delhi should use ‘summit diplomacy’ to ensure viable conflict resolution between adversarial parties. Going forward, India can mediate international conflicts as its “multi-alignment policy” affords it the agency to befriend all countries in the international arena.

If India wishes to be a ‘first responder’ to international conflicts rather than a hesitant bystander, New Delhi should use ‘summit diplomacy’ to ensure viable conflict resolution between adversarial parties.

India’s History of Mediation

From local level village conflict to the courts, the idea of mediation (madhyasthata) as an instrument of conflict resolution has been a part of the Indian legal discourse and social fabric for centuries. The Mughal state emerged as a ‘patrimonial bureaucratic state’ where mediation was practiced to resolve military conflicts. Mediation continues to be prevalent in the Indian constitution today as an ‘Alternative Dispute Resolution’ method under Section 89 of the Code of Civil Procedure.

However, India has not incorporated mediation as a practice in international conflict resolution, despite making attempts at institutionalizing it by passing the Mediation Bill, 2021 and being a signatory to the Singapore Convention on Mediation. India’s hesitation to mediate international conflicts is possibly linked to its own opposition to third-party mediation for its own conflicts, such as the Kashmir issue which New Delhi views as a bilateral dispute between India and Pakistan.

Despite this hesitation, since 1947, India has heralded a rich legacy of organizing and engaging in summit diplomacy and using it as a tool of conflict resolution. For instance, the Indian think-tank, Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA), organized the Asian Relations Conference in 1947 where India invited Korean delegates during their “foreign military trusteeship period” under the United States Army Military Government in Korea (UAMGIK) and espoused the cause of Korean independence. Similarly, as a founding member of the non-aligned movement (NAM), India organized and participated in several NAM summits, providing India the opportunity to lead the Third World States (TWS) immediately after their emergence, without entering ideological camps during the Cold War.

India has sporadically engaged in international conflict mediation, both during the Korean crisis (1956) and the Vietnam crisis (1979). In both these conflicts, India assisted in peace building initiatives through the use of non-traditional forms of peace building, such as by containing the conflict and its escalation. India led the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) and conducted ‘peaceful and highly representative elections’ in 1948 that led to the creation of the first democratically elected government in Korea. Similarly, India led the International Commission for Supervision and Control during the Vietnam War (1954-65) and tried to negotiate the conflict.

After the end of the Cold War, track 1.5 summits – informal platforms comprising official actors like diplomats, and unofficial actors like academics – such as the ‘Delhi Dialogue’, have also enabled India to provide a platform for global leaders to address issues of common concern like poverty and global warming. Indian philosophical principles like Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (The World is one Family) have guided Indian thinking on the international stage.

A further push towards summit diplomacy emerged over the past decade with the ‘Raisina Dialogue’ in 2016. As a dialogue to promote the ‘Indian perspective on Foreign Policy’ on the global stage, the dialogue has become India’s voice on issues of significance like international security, maritime cooperation, climate change, and public health.

Raisina Dialogue & the Russia-Ukraine War

The 2023 edition of the Raisina Dialogue coincided with India’s G20 Presidency and the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war. A major highlight of the dialogue included a bilateral meeting with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, which saw his verbal pyrotechnics at play as he blamed NATO for the ongoing war. While Western diplomats used Raisina to criticize the invasion, India, as the host, continued to walk a diplomatic tightrope on Russia, choosing to safeguard its ties with Moscow. India did not officially make any explicit reference to the Russia-Ukraine war during the dialogue and lamented that ‘the war had hijacked the conversation’ when the topic of discussion had to revolve around the notion of sustainable development and the Global South.

In 2022, India had emphasized “stopping the fighting and getting the talking” done. But, as the war has progressed, India has tacitly defended Russian interests, in keeping with its policy of “multi-alignment” which enables India to befriend countries despite their contrarian ideological affiliations.

India’s response at Raisina was an example of realpolitik as India chose to protect its national interests. While India denounced Russia’s nuclear threat, it refrained from directly condemning the invasion. Russia is India’s largest supplier of defense equipment and Russian military equipment supplies are critical to the functioning of the Indian armed forces. Similarly, Russia has traditionally supported the Indian stance on the Kashmir issue in the United Nations, and emerged as an “all weather ally” of India during the East Pakistan crisis (1971).

Raisina Dialogue 2023 — A Missed Opportunity?

India had the opportunity to serve as a ‘problem solving mediator’ in the Russia-Ukraine war through Raisina. Moving ahead, India could adopt an informal approach to mediation similar to the ‘ASEAN Way,’ involving non-interference, ‘quiet diplomacy’, discreet negotiations, and informal channels, so that it can secure its own national interests while also acting as a mediator. India could have potentially engaged with minilateral forums such as I2U2 on the sidelines of the dialogue and even included other members of the G20 like Turkey on the negotiating table to broker peace. Since Turkey has previously negotiated an agreement on grain exports between Russia and Ukraine, it is in a position to ensure negotiated peace between the two states. Finally, India can use platforms like the Raisina Security Dialogue to bring the military chiefs/attaches together to provide an informal platform to contain the conflict.

If India does not mediate in the conflict, it will weaken its position as a moderate normative power within its immediate neighborhood that supports the tenets of democracy, rule of law, and opposes irredentist tendencies.

If India does not seize the opportunity, India’s competitors like China will do so, limiting Indian influence in international politics. China has already brokered peace between Iran and Saudi Arabia and has mediated in conflicts like the Myanmar-Bangladesh Rohingya conflict. Similarly, if India does not mediate in the conflict, it will weaken its position as a moderate normative power within its immediate neighborhood that supports the tenets of democracy, rule of law, and opposes irredentist tendencies, making the neighborhood wary of India’s intentions.

During a recent visit to India, Ukrainian Deputy Foreign Minister Emine Dzarapova called for Ukraine’s participation at the G20 meeting in September 2023. Russia has also requested India to mediate in the war in the past. It is time that India performs its role as the chair of the G20 and provides an informal platform to contain this war.

Also Read: Indian Irredentism and the Ukraine Crisis

***

Image 1: Raisina Dialogue 2023 via Flickr

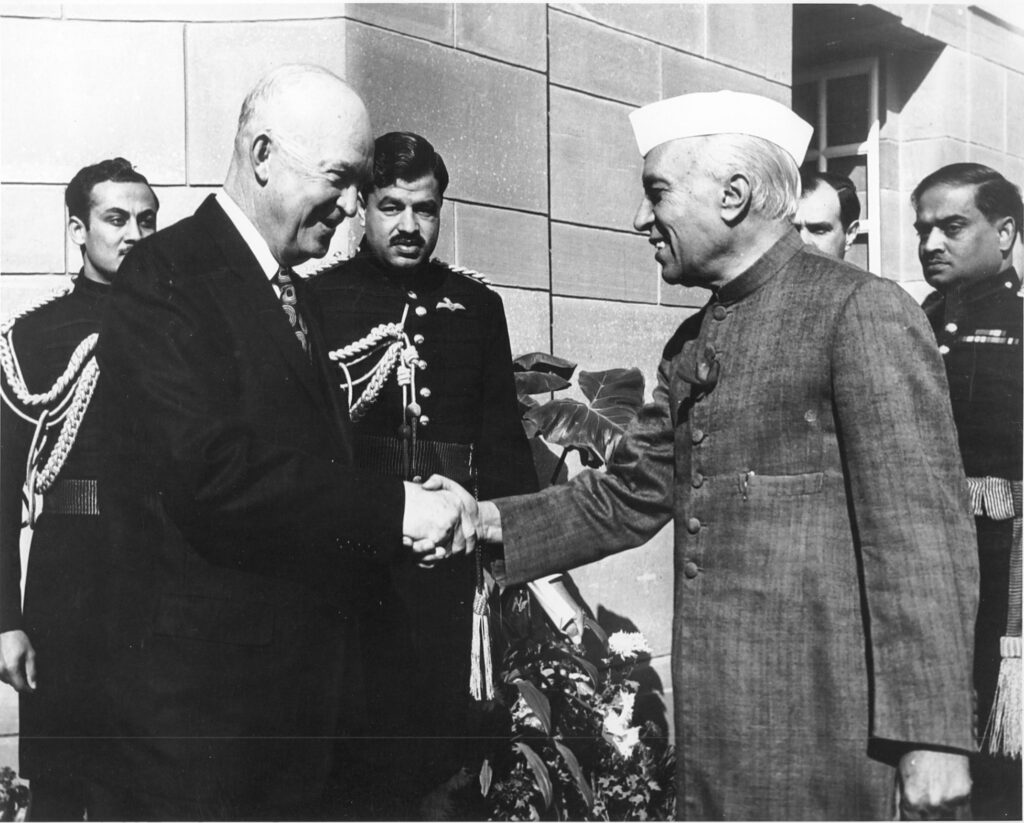

Image 2: President Eisenhower Visits India via Flickr