The Russian military invasion of Ukraine has caught many within the international community by surprise. The past five weeks of the Russian attack have had severe humanitarian consequences for Ukrainians, disproportionately impacting women and girls. But despite reports from the ground confirming the adverse effects of the intensifying Russian offensive on women in Ukraine, feminist perspectives are continually sidelined from mainstream discussions of the war.

While South Asian countries have received flak for not taking a direct stance on the conflict, they can still play a pivotal role in protecting women’s rights and security in Ukraine. These countries can do this by mainstreaming gender in humanitarian assistance, calling for the inclusion of women in the negotiation process, and developing customized capacity-building strategies, all while still maintaining neutrality.

Gender Security Parallels: South Asia & Ukraine

Ukraine’s humanitarian situation—especially regarding the protection of women and girls—is rapidly deteriorating amid Russia’s untiring intervention. Evidence emerging from the ground suggests that women account for nearly 54 percent of people in Ukraine who need urgent assistance. Moreover, women and children comprise a vast majority of the 2.3 million refugees that have fled to neighboring countries to escape the war. As this conflict continues to escalate, women are at an increased risk of gender-based violence with limited national or international accountability.

While South Asian countries have received flak for not taking a direct stance on the conflict, they can still play a pivotal role in protecting women’s rights and security in Ukraine.

The current Ukraine-Russia crisis has exacerbated a difficult period for Ukrainian women, many of whom have seen major economic and social setbacks during the last two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. But despite these newly emerging challenges, women in Ukraine are far from mere spectators of the conflict and have even taken up arms to protect their country. According to the Ministry of Defense, there were approximately 57,000 women in the Ukrainian armed forces at the beginning of 2021. And as the offensive continues, these numbers are only expected to increase further.

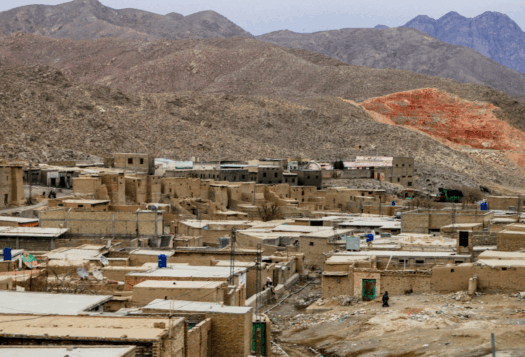

However, the situation for women in Ukraine has ongoing parallels in South Asia, including in Afghanistan—a country still grappling with the consequences of a multi-decade-long war. Ever since the Taliban re-established their power over the country, they have drastically curtailed women’s rights by prohibiting them from attending schools and colleges, banning their appearances in public spaces without a male chaperone, enforcing a strict dress-code, and blocking employment opportunities.

As a result, Afghan women today face a similar predicament to their Ukrainian counterparts, as both groups grapple with increased violence and torture that necessitate fleeing their respective home countries.

Even in other South Asian countries without imminent conflict, heavy militarization and enhanced state security have put women’s lives and freedom at stake. We have seen this in parts of India’s Northeast region, where the imposition of the Armed Forces Special Power Act (1958) has provided legal cover for officers who often abuse their power to sexually assault, harass and rape women.

Based on numerous years of experience and learning, governments in South Asia could provide more assistance for the incorporation of a gendered perspective in response strategies, advocate for women’s participation at all levels, and provide support in furthering women’s development, which will all contribute towards protecting and upholding the rights of the Ukrainian women stuck in the middle of the Russian invasion.

The South Asia Pivot: WPS

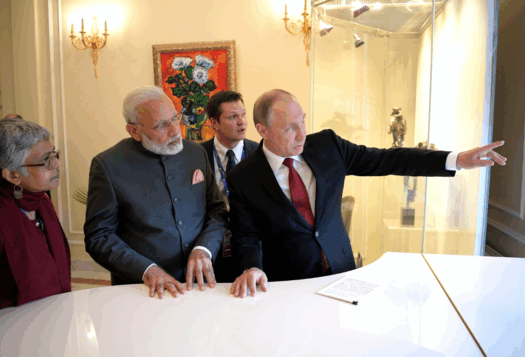

Russia’s Ukraine invasion has created a conundrum where both India and Pakistan are in a delicate bind due to India’s close defense partnership and the Pakistan’s burgeoning economic relationship with Russia. Many in Afghanistan fear that the exploding conflict could distract from its humanitarian crisis. Other South Asian states do not want to risk running afoul of sanctions regimes due to their own economic fragilities. As a result, most countries in the region are yet to take a definitive stand on the conflict.

However, the current situation demands fostering a culture of accountability for women’s rights and security in Ukraine. And the countries of South Asia, which have been making advances to inculcate a culture of gender equality for some time now, could—without taking sides—work towards filling this gap and do their part to advocate on behalf of the concerns that Ukrainian women face.

Countries in South Asia could push for the development and stimulation of a joint commitment between the region and the Ukrainian government to advance the implementation of United National Security Council Resolution 1325: Women, Peace, and Security (WPS). UNSC Resolution 1325 calls for the protection and meaningful participation of women in all levels of conflict resolution. Invoking the resolution will not only help in upholding the rights of Ukrainian women but also reaffirm the region’s commitment to women’s empowerment, especially in light of South Asia’s poor track record on gender-based violence.

The governments of South Asia and Ukraine should also work together to incorporate and mainstream a gendered lens to any humanitarian assistance and aid provided to Ukraine. It is also crucial that South Asian countries develop specialized humanitarian programs and target financial support that would effectively be able to mitigate the disproportionate repercussions that women bear from the conflict. South Asian countries could set an example by keeping the issues and demands of women a focal point while designing humanitarian assistance and programs for Ukraine.

South Asian member states in the UN and other international fora could additionally leverage their relationships with Russia and Ukraine to push for a more gendered approach to negotiations. As of now, women have mostly remained missing from both the Ukrainian and Russian negotiation delegations. Even NATO—which would play a significant role in preventing an escalation of the Russia-Ukraine conflict—has yet to publicly articulate the relevance of gender in their response to Russia’s intervention in Ukraine. The positions of South Asian countries could perhaps provide a renewed focus on gender security in the conflict by demanding the inclusion of more women in the negotiation process.

And the countries of South Asia, which have been making advances to inculcate a culture of gender equality for some time now, could—without taking sides—work towards filling this gap and do their part to advocate on behalf of the concerns that Ukrainian women face.

But to bring women to the table and ensure their participation in conflict negotiations, it is also necessary to equip them with the necessary techniques and tools. South Asian countries could formulate specific strategies to extend the provision of capacity-building exercises between women in South Asia and women in Ukraine to help and train them as peace-builders or as negotiators and first responders at all levels—regional, national or local.

Conclusion

While governments in South Asia are still grappling with gender inequality throughout their own region, pushing for the implementation of a WPS agenda in Ukraine could help the member states assist with the humanitarian crisis in Ukraine without strictly condemning Russia. Implementing the WPS agenda in the Ukraine conflict could ensure greater participation of women and gender mainstreaming across all aspects of Ukraine’s conflict resolution, which might further lead to a more demilitarized approach and a peaceful resolution to the conflict.

***

Image 1: Sudip Karmakar via Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: UN Women via Flickr