South Asian states have historically struggled to coordinate meaningful regional cooperation. In 1985, South Asian heads of state created the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), which has since failed to accelerate regional cooperation without summit meetings held since 2014. The Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-sectoral Scientific Technological Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), established in 1997, has not assumed its dynamic posture even with Pakistan excluded and Myanmar included. South Asia remains one of the least integrated regions in the world.

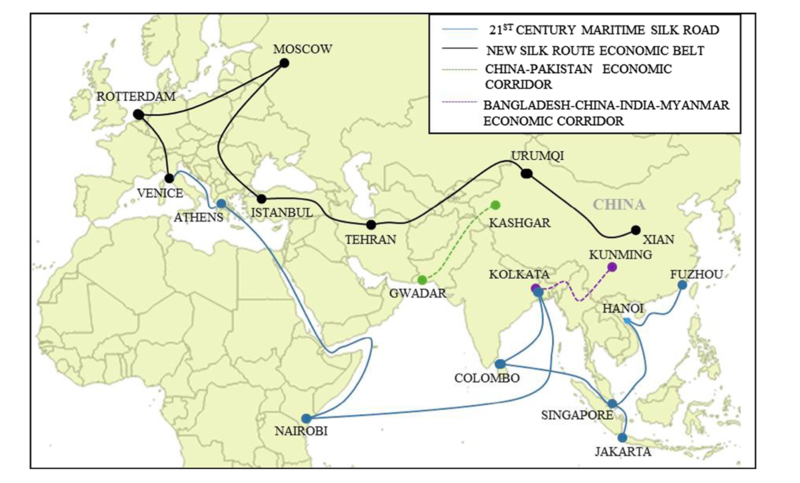

Instead, outside countries have shifted their efforts to cultivate bilateral relations with South Asian countries. As China attempts to foster regional connectivity through its Belt and Road Initiative, this piece will review China’s development approach in South Asia over the past decade through the construction of the three economic corridors—China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), and Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIMEC).

The Driving Forces of Building Economic Corridors in South Asia

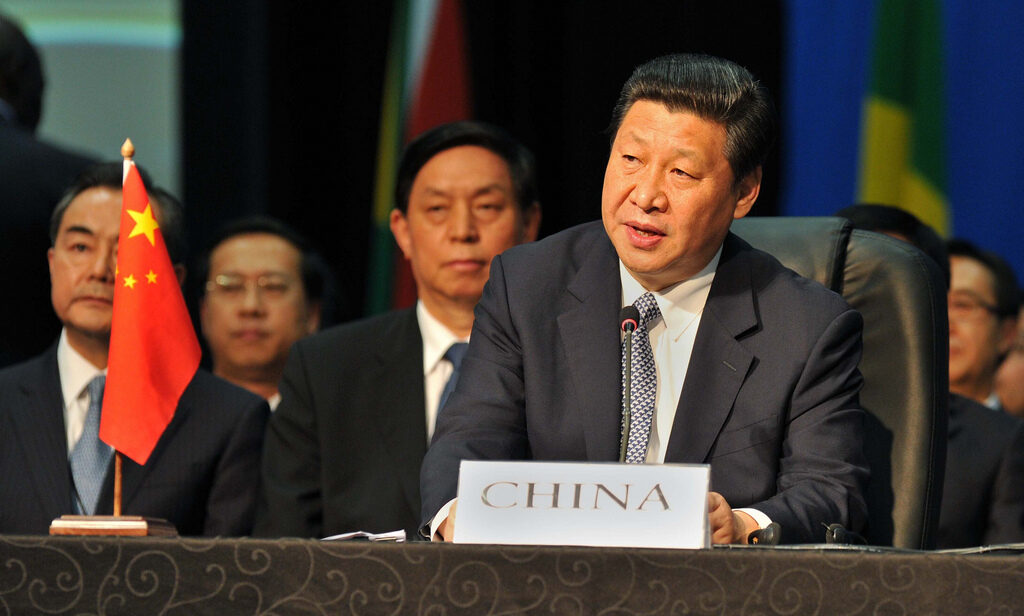

Xi Jinping assumed leadership of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012, and the Chinese government announced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. China’s new development strategy befitting its role as the world’s second-largest economy. Nicknamed “the World’s Factory,” China had built a comprehensive manufacturing and supply chain system and become the largest trading partner for most states in Asia. China’s increased financial and technological capabilities meant it could cultivate opportunities for trading and investment abroad, particularly in its neighborhood and at sites of strategic importance throughout South Asia. China focused on cultivating bilateral and trilateral relations with South Asian states by pursuing three chief development lines of effort within its broader BRI. While significant progress has been made in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), implementation of the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor has faltered.

As growing China-U.S. tensions ushered in the return of great power competition in the Indo-Pacific region, Chinese policymakers and security strategists have searched for a resolution to the so-called “Malacca Dilemma.” Over 60 percent of China’s oil and natural gas imports from the Persian Gulf and Africa must transit through the Strait of Malacca. The global impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war have only reinforced for Chinese policymakers the risk of this chokepoint in the event of military conflict. The infrastructure development conducted through CPEC and CMEC would offer China an alternate land route to reach the Indian Ocean. Consequently, since the independence of Myanmar and Pakistan, China has nurtured strong relationships with whichever military authority or political party held power.

China’s increased financial and technological capabilities meant it could cultivate opportunities for trading and investment abroad, particularly in its neighborhood and at sites of strategic importance throughout South Asia.

Three principles have been highlighted in the negotiations between China, Pakistan, and Myanmar, respectively. Any proposed project within the economic corridor should have broad consultation, joint contribution, and shared benefits, realizing the win-win results between the two contracting parties. However, these states’ financial weakness, infrastructural struggles, and energy shortages have hindered development projects. China’s investments in transportation, energy, and agricultural development have been warmly welcomed by Myanmar and Pakistan alike.

History and Progress of BRI in South Asia

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)

Pakistan has enjoyed a special place in China’s neighborhood diplomacy. In 2015, China and Pakistan established the All-Weather Strategic Cooperative Partnership and have stayed committed to building a closer China-Pakistan ‘community of shared future.’ The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) officially kicked off in 2015, aiming to connect China’s Xinjiang to Pakistan’s Gwadar Port. The sea-and-land route offers a route avoiding Malacca for China’s energy imports, while Pakistan aims is to overcome an electricity shortfall, develop infrastructure, and modernize its transportation networks.

China has referred to CPEC as a revival of the Silk Road. Originally valued at USD $46 billion, the value of Chinese investment in Pakistan rose to USD $65 billion in 2022. CPEC projects have rapidly upgraded Pakistan’s transportation networks, created numerous energy projects, and special economic zones. CPEC is expected to create 2.3 million jobs between 2015 and 2030 and add 2 to 2.5 percentage points to Pakistan’s annual economic growth. As of 2022, China has enhanced Pakistan’s exports and development capacity and provided one-fourth of its total electricity. The two countries appear satisfied with the steady progress of CPEC projects, and they have created a joint coordination committee and made their commitment to the high-quality development of CPEC. Pakistan and China have agreed to enhance development cooperation in Afghanistan as well, including by extending CPEC to Afghanistan.

However, several local political parties and insurgent armed forces have raised objections against the CPEC projects in Balochistan, and they have even attacked the facilities and the Chinese nationals associated with the CPEC projects. Pakistan’s political instability and frequent change of government have also had remarkable impacts on the implementation of the CPEC projects. These factors continue to limit the full potential that CPEC offers.

The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor

Since the 1950s, in official documents, China and Myanmar have described their relationship as “pauk-phaw,” the Burmese word for siblings. Former Chairman of Myanmar State Peace and Development Council Than Shwe recently stated that this close bond was forged by the older generations’ leaders and has been promoted by every generation since and is deeply rooted. As a country mired in extended domestic conflicts, Myanmar’s infrastructure construction lags far behind its ASEAN partners. Its poor transportation system, shortage of electricity, and other facilities have long hindered foreign investment, economic growth, and improvement of people’s livelihood.

China has viewed its friendly relations with Myanmar from a strategic perspective and has worked with both military and civilian governments to develop the China-Myanmar comprehensive partnership. The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) was initiated by the Chinese government and Myanmar NLD government as part of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2017. Like CPEC, CMEC has provided China with another outlet in the Indian Ocean.

CMEC plans to use highway and railway transportation to connect the Yunnan Province, through Muse and Mandalay, to Kyaukphyu, the seaport city in Rakhine State, using the gas and oil pipelines built in 2013 and 2017. Additionally, a Special Economic Zone is set to be developed at Khaukphyu as part of the initiative. The railway will link to the Chinese railway network at Ruili, Yunnan province.

As an important part of the CMEC corridor, three core zones are expected to be established along the border areas of both countries. The core zones will be commercial areas with duty-free concessions, hotels, manufacturing, and financial services. The core zones would be Muse and Chinshwehaw in the northern part of Shan State and Kan Pite Tee in Kachin State.

Another CMEC pillar, the China-Myanmar oil and gas pipelines began operation respectively in 2013 and 2017. The two parallel pipelines start from Myanmar’s western Kyaukphyu on Made Island port, then run through central Myanmar before entering China’s border city of Ruili in Yunnan province. As China’s fourth strategic energy supply channel, these two pipelines are of vital value to its energy supply diversification. These pipelines have also created lucrative sources of income and employment opportunities for Myanmar’s local residents and eased the energy supply pressure in the areas along the pipelines. By the end of 2019, the two pipelines had brought about $520 million in direct revenue to Myanmar.

As far as the implementation of the CMEC projects is concerned, the military coup overthrew the NLD government and jailed its leaders in 2021, delaying the progress. The major CMEC projects that have been planned and implemented in the region are actually controlled by the ethnic armed forces, not by the military regime, the uncertainty and insecurity of the related projects remain. The efforts to reinstate a civilian federal government through open and fair elections are also unpredictable.

The Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIMEC)

Bangladesh, China, India, and Myanmar initiated the BCIMEC in 2014 to create a sub-regional ‘cooperation zone’ or ‘growth zone’ which would connect the land-locked and relatively less developed areas of China’s Southwest to India’s Northeast with the Least Developed Countries of Bangladesh and Myanmar. BCIMEC’s flagship initiative is the route connecting Kolkata to Kunming and going through Mandalay in Myanmar as well as Dhaka and Chittagong in Bangladesh. The corridor is designed to facilitate transportation connectivity, trade linkages, and cultural and religious tourism. Since BCIMEC areas are dotted with tourist destinations, the BCIMEC could play an important part in terms of developing eco-tourism and religious tourism. All four countries are expected to gain from more extensive market access for goods and services by eliminating tariff and non-tariff barriers together with the development of supply and production chains.

The corridor is designed to facilitate transportation connectivity, trade linkages, and cultural and religious tourism.

However, the Indian government has rejected BRI, which it views as concentrating China’s power in strategic border areas. CPEC passes through an area in Pakistan-administered Kashmir that India alleges is its land. Similarly, the Indian national security establishment believes that CMEC will make it easier for ethnic insurgencies in India’s northeast to move goods and people. Given India’s strong resistance, China, Bangladesh, and Myanmar have shifted their efforts to create Bangladesh-China-Myanmar Economic Corridor. These three governments have already supported the BCIM. China is the largest trading partner and a major investor in Bangladesh. After the implementation of the CMEC projects, the BCMEC would be well reasoned and greatly shorten the Bangladesh-China trading route.

Lessons Learned from the EC Construction

Based on the achievements and failures of the economic corridor construction within the BRI framework, we have learned three lessons.

First, any economic cooperation initiative must be based on politically mutual trust and cooperative security. Otherwise, any economic cooperation initiative cannot be sustainable. The most salient case is that the BCIM Economic Corridor came to a premature end.

The second lesson is that any economic cooperative arrangement must be complementary, mutually beneficial, and bring win-win results among the member parties. The substantial progress of the CPEC and CMEC has been driven by such mutual benefits and complementarity.

The third lesson is that any economic cooperative project must take environmental issues into full consideration and bear social responsibilities by contributing to local education, health, and living standards. In order to reduce carbon emissions, China has shifted its focus from coal-based energy investments in Pakistan to renewables. The Karot Hydropower started commercial operations to provide clean electricity in 2022.

The Chinese government has worked hard with the relevant governments to realize sustainable, green, and high-quality development.

Also Read: China in South Asia: CPEC and the Indo-Pacific at the Heart of China-Pakistan Collaboration

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: President of the People’s Republic of China, Mr. Xi Jinping via Flickr

Image 2: The plan of OBOR via Wikimedia Commons