As China extends its influence in the region through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Afghanistan has begun to receive its attention, both diplomatically and economically. Notably, China served as mediator between Pakistan and Afghanistan when it facilitated a trilateral dialogue last year, where Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi advocated Afghanistan joining the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). More recently, at the informal summit between President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India and China agreed to implement a joint economic project in Afghanistan.

These initiatives are related: each reflects Beijing’s pursuit of its own economic interests. In light of this, India must be wary of moving forward with China on a project in Afghanistan that could help Beijing gain at the expense of India’s interests and, potentially, the long-term stability and prosperity of Afghanistan.

Strategic Significance of CPEC

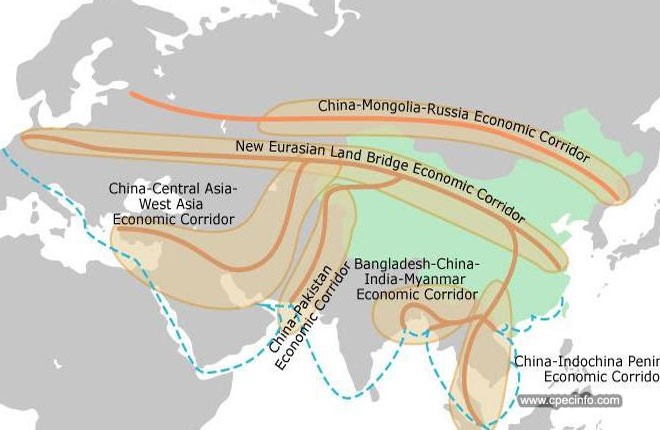

The 3,000 kilometer-long CPEC, the flagship project of the BRI aimed at bolstering regional connectivity and cooperation, starts from the Chinese city of Kashgar and ends at Pakistan’s Gwadar port. The corridor aims at furthering regional connectivity through improved road, rail, and air transport; people to people contact; and academic, cultural, and trade exchanges. CPEC also strategically connects to the Silk Road Economic Belt in the north and the Twenty-First Century Maritime Silk Road in the south, the sea- and land-based components of the BRI respectively.

India must be wary of moving forward with China on a project in Afghanistan that could help Beijing gain at the expense of its interests.

The strategic significance of CPEC is linked to China’s western development strategy. It has become important for China to bolster economic growth in its western provinces, as the coastal provinces of China—the erstwhile drivers of growth—are now suffering from mismatched supply and demand, with the production of everything from iron to steel to real estate outnumbering the demand for such products. Several investors, both foreign and Chinese, are now looking west towards inland China to benefit from low labor costs and the growing markets. With this in mind, the 13th Five Year Plan, adopted in March 2016, places special emphasis on the western regions. The development of the western provinces is closely tied to the countries bordering them—such as Afghanistan and Pakistan—through which transit will become necessary for investment as well as in the search for markets. Economic corridors like CPEC allow Beijing to make inroads into new markets, increasing the consumer base for these industries outside of China.

Source: China Pakistan Economic Corridor Website

Need for an Extended CPEC

Primarily, China envisions harnessing Afghan territory for transit routes to the Middle East and Central Asia through Xinjiang, a province in western China that borders Afghanistan. China is geographically surrounded by oil and gas resource rich countries, from the Middle East to Central Asia. It has already invested in pipelines to import oil and gas from Central Asia and Russia, but what remains is connecting these resource-rich regions to China by overland trade routes. According to Wang Yi, the proposed extension of CPEC through Afghanistan will connect CPEC and the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor, which run parallel to one another. To this end, the extension of CPEC through Afghanistan is necessary to bridge this connectivity gap between China, Central Asia, and the Middle East.

Following the trilateral dialogue in December, he had stated that Kabul was “willing to join” the multi-billion dollar corridor and warned India not to disturb or influence the project. While Afghanistan has not officially confirmed its participation in an extended CPEC, its scope for bringing economic development—the stated intention of all BRI projects—to the war-torn country should be of interest to Afghanistan: the country is rich in natural resources, but has been unable to reap the economic benefits of this wealth due to conflict. For these reasons, it can be argued it is only a matter of time before Afghanistan officially agrees to join the extended CPEC.

A Question of Motive: Comparing India and China

New Delhi’s decades-old engagement with Kabul has traditionally been aimed at promoting long-term stability and economic prosperity in Afghanistan. Since the Taliban government was toppled in 2001, India has provided assistance to the country, becoming its biggest regional donor and constructing more than 2,500 miles of roads, dams, hydropower plants as well as the country’s new parliament building. India’s support and collaboration also extends to the rebuilding of air links, the construction of power plants, and investments in the health and education sectors, as well as the training of Afghan civil servants, diplomats, and police. This soft power approach has made India popular among Afghans, and there is a well-documented perception in Afghanistan that India is a trusted friend.

In contrast to Indian efforts in Afghanistan, China’s engagement hinges on economic self-interest. This is exemplified through the case of the Mes Aynak copper mines, for which China struck a $3 billion deal USD in 2007. However, extraction at the Mes Aynak site has yet to begin due to militancy. While likely frustrating for China, the situation does not necessarily represent a failure of Beijing’s economic involvement in Afghanistan. According to Sameer Lalwani, senior associate and co-director of the Stimson Center’s South Asia Program, China realizes that extractive efforts require high “front-end conflict management and stabilization costs.” Instead, its strategic objective in Afghanistan is most likely “to contain instability from spilling out and disrupting its other economic equities in the region.” Thus, rather than being all-in on any one investment opportunity, China is likely more preoccupied with integrating Afghanistan into its vision for BRI while promoting stability to facilitate the formation of long-term economic linkages between western China, Afghanistan, and Central Asia.

China recognizes the opportunity to link itself to India’s popular reconstruction and stabilization efforts in Afghanistan while continuing to pursue its efforts with the extension of CPEC.

This is where China may see India’s efforts in Afghanistan as useful: it recognizes the opportunity to link itself to India’s popular reconstruction and stabilization efforts in Afghanistan while continuing to pursue its efforts with the extension of CPEC, in hopes of one day creating a convergence between its connectivity endeavors and New Delhi’s initiatives in Afghanistan. If the India-China project in Afghanistan takes off, Beijing will undoubtedly continue with its pursuit of getting India on board with this vision, although New Delhi has maintained its objections to CPEC and BRI as yet.

A Tale of Two Visions

Though the details of the joint economic project between India and China announced at Wuhan have not been made public yet, conflict may emerge between India and China’s visions for Afghanistan if the project materializes. With Beijing’s interests lying in securing its own economic gains, India must remain cautious of China’s intentions with any joint economic project and staunchly guard both its interests and the long-term stability and prosperity of Afghanistan.

***

Image: MEAphotogallery via Flickr