The bulk of the discourse on South Asian security is focused on inter-state rivalry, border demarcation, nuclear threats, or terrorism. On the other hand, environmental challenges, such as climate change, water scarcity, and energy security, have received scant attention. The recent floods in Bombay, Dhaka, and Colombo—caused either by heavy rain or cyclones—are examples of what could become an increasingly common reality for the region. These increasingly frequent climate change-induced natural disasters give significant weight to the idea that policymakers in South Asia must begin to conceptualize climate change as a pressing security issue.

Due to the dependency of South Asia’s rural poor on agriculture as a source of livelihood, the region’s population is particularly vulnerable to climate change-induced disasters such as flooding and intense heat waves. In the summer of 2015 alone, heat waves killed 3,500 people across South Asia. Such events are likely to become more and more frequent as global temperatures rise, with experts projecting that the massive heat will decrease crop yields by a projected 15-30 percent by the mid-twenty-first century. Meanwhile, rising sea temperatures—a major indicator of climate change—made last year’s monsoon season more intense by increasing the moisture in the atmosphere. These rains were devastating, costing more than 1,200 people their lives and affecting a total of 40 million people across India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. If global temperatures rise as predicted between 2° to 4.9° by the end of this century as a result of climate change, the burden placed on South Asia’s strained food and water resources will only intensify as disasters such as these become increasingly common.

The immediate impact of climate change-induced disasters will be seen in terms of the movement of people across the subcontinent in search of better and safer living conditions. Crossborder migration from Nepal into India, a phenomenon that is already so common due to the open border between the two countries, could drastically increase as a result of extreme events like floods and landslides. The movement of people from Bangladesh to India due to slow onset events like rising sea levels or sudden onset disasters such as cyclones is another distinct possibility. In the case of Bangladeshi migrants into states in India’s Northeast region, an uptick in migrant flows could exacerbate tensions over existing patterns of illegal immigration. These tensions have already boiled over in 2012 in clashes between the Bodo tribe and the Muslim community, the latter of which was formed largely due to increasing number of unauthorized Bangladeshis to the state. Across South Asia, poverty, political violence, and displacement are already all too common. With added water and food insecurity due to climate change, competition over resources might intensify clashes between local inhabitants and newly relocated people across South Asia, with the result of destabilizing the subcontinent.

While some may argue that this slow threat is less demanding and time-sensitive than threats of terrorism or nuclear dangers, South Asian countries addressing climate change as a security concern is imperative. Within South Asia, Bangladesh and the Maldives have been at the forefront of the fight against climate change and instituted action plans to adapt to and manage the consequences of climate change. Bhutan has also been actively working towards climate change mitigation, which is evident as it is the only carbon negative country in the world. While India has formulated a national action plan against climate change and set ambitious renewable energy targets and Pakistan recently passed a Climate Change Act to implement action, the two countries continue to give much higher priority to traditional security threats like border issues and terrorism in their national security policies due to the hostile relationship between the two nations and do not necessarily consider the threat of climate change when formulating policies. While these traditional threats cannot be discounted, New Delhi and Islamabad would do well to seriously acknowledge the security threats emanating from climate change and divert some of the military’s budget to combating the inevitable effects of climate change in South Asia.

As long as India and Pakistan are unwilling to regard climate change as a security threat, perhaps other South Asian countries such as Nepal could take up a leadership position and address environmental security concerns in the region. Since Nepal is the current chair of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), reviving the regional organization—which has been in a coma since the cancellation of the SAARC Summit that was to be held in Islamabad in 2016—with policy dialogues pertaining to climate change and renewable energy policies could be a good starting point. South Asia’s combined solar, hydro, and wind power potential is high enough to satisfy the region’s energy demands while limiting greenhouse gas emissions. A well-orchestrated regional or subregional effort to harness the subcontinent’s collective strength in this area would be effective in mitigating the effects of climate change. Another top priority must be bilateral and multilateral attempts to coordinate effective disaster response mechanisms across the region to mitigate the damage done by climate change-induced disasters.

South Asian security policy circles must recognize that nontraditional security threats like those emanating from climate change will ultimately be as intimidating as traditional security threats. They must look both inward and outward, simultaneously rethinking conceptions of security internally while cultivating regional cooperation. We will only fully realize the gravity of the climate change-security nexus when we stop equating security with warfare and make adequate space for confronting the destabilizing effects of climate change.

***

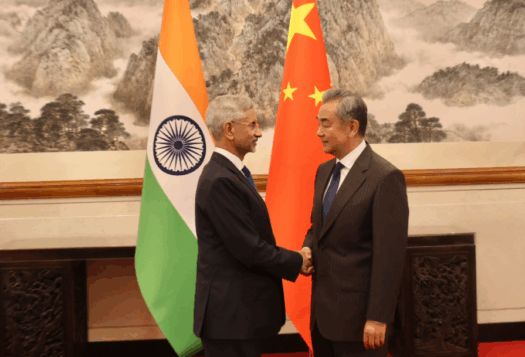

Image 1: Amir Jina via Flickr

Image 2: NurPhoto via Getty