Since President Xi Jinping launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, Indian and Western analysts have consistently characterized China’s participation in South Asian development projects as a harbinger of geopolitical realignment and a thinly disguised attempt at Chinese military expansion. Reinforcing these concerns are recent reports of increased military cooperation between China and Pakistan under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). By contrast, Chinese sources define BRI as promoting “mutual respect,” “win-win cooperation,” and building “a community of human destiny together.” Such rosy rhetoric is typical of China’s state-controlled media, but provides little insight into the actual outcomes of the initiative. Instead, the unique cases of two active participants in BRI, Nepal and Sri Lanka, can provide a blueprint for navigating potential opportunities and hazards presented by Chinese investment projects.

Sri Lanka: ACautionary Tale

Colombo’s dealings with Beijing may serve as a warning for other BRI member states given the failure of Chinese-led mega-projects in Sri Lanka, in particular the Hambantota Port. Because returns from the port project were insufficient for Sri Lanka to pay back Chinese loans, the port was eventually “handed over” to China on a 99 year-long lease. This inspired countless accusations of Beijing’s calculated infringement on the national sovereignty of its neighbors, as well as of its military aspirations in the Indian Ocean. The project’s failure speaks to inadequate due diligence on the Chinese side and the reputational hazards of opportunism but that is not the complete picture–domestic corruption in Sri Lanka also had a role to play.

A 2006 feasibility study conducted by a Danish consulting company reportedly offered a positive outlook for the project, which supported the optimistic predictions made by Sri Lankan port authorities. However, engineers encountered unanticipated challenges during construction, which were compounded when the port’s completion was rushed to fall on then president Mahinda Rajapaksa’s birthday. The unrealistic timeline resulted in greater expenses and limited accessibility to the port after it was opened. Thus, Sri Lanka’s debt problem in part originated from domestic mishandling and unrealistic objectives set by the Rajapaksa administration.

China’s indiscriminate approval for Sri Lankan authorities’ overly ambitious mega-projects ultimately proved costly not only for Sri Lanka, but also resulted in long-term reputational consequences for other Chinese projects, and undermined other countries’ perception of China as a source of foreign investment. Hambantota can serve as a lesson for similarly positioned countries, who should make careful assessments of their debt capacity for such projects both when signing onto and throughout the course of such projects.

Nepal: At aCrossroads

While the SriLankan example highlights the dangers of leaning heavily towards China withoutadequately considering the costs, Nepal’s efforts to leverage Sino-Indiancompetition to secure its interests can serve as a useful model for other smallstates on how to more effectively engage in great power management.

Although India is Nepal’s traditional provider of development investment, China has taken greater initiative in the country in recent years. This has resulted in competitive bidding for projects of increasingly larger size and cost—such as the construction of five mega hydropower plants, two of which will be built by China and three by India.

Nepal has maintained a generally welcoming attitude towards Chinese investment, despite warnings from Western analysts that Chinese investment is fraught with “debt-traps”—warnings that hold greater weight in the aftermath of Hambantota. Such openness seems to indicate that Nepal has made the determination that engaging with China can increase its bargaining power in relation to India. In this way, strategic competition between India and China can serve to increase Nepal’s leverage, allowing Kathmandu to carefully consider the pros and cons of Chinese and Indian deals, rather than simply accepting whatever is offered.

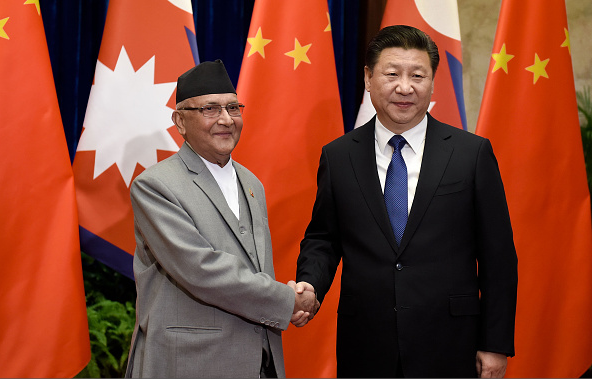

Nepal’s need for infrastructure development dictates that it cannot preclude cooperation with either India or China. Thus, to maximize its bargaining power, Nepal appears to have a strategy in place since its new prime minister, KP Sharma Oli, took office last year, of intentionally avoiding taking sides in Sino-Indian competition. Although Oli ran on a China-leaning platform during his campaign at a time of strong anti-India sentiment sentiment in Nepal, he has since maintained a friendly and respectful attitude towards India and left the door open for cooperation with the country, even making his first official visit after entering office to New Delhi. At the same time, he has also maintained fruitful ties with China, continuing their cooperation under BRI and Nepali President Bidya Devi Bhandari is attending the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing this week.

Hedging Strategies for Small States

The apparent ability of Sri Lanka and Nepal to expand economic ties with their two giant neighbors simultaneously indicates that the building of economic partnerships is not a zero-sum game. Despite Indian fears of China taking its place as the regional leader of South Asia, other small countries in the region should view the Sino-Indian dynamic as an opportunity for increased cooperation, rather than an ultimatum.

The Nepali and Sri Lankan cases provide insight into strategies that small states can utilize, both to be equidistant from competing powers as well as how to course correct if they have gone too far in one direction. For example, in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s handing over of Hambantota to China, the Sirisena administration was able to attract greater investment from India after acknowledging the country’s overdependence on Chinese investment, thereby increasing Indian economic engagement with Sri Lanka. At the same time, Nepal’s Prime Minister Oli has publicly stated that he welcomes investment from both India and China, while encouraging greater cooperation between the two countries. This apparent ability of Sri Lanka and Nepal to expand economic ties with their two giant neighbors simultaneously indicates that the building of economic partnerships is not a zero-sum game. Despite Indian fears of China taking its place as the regional leader of South Asia, other small countries in the region should view the Sino-Indian dynamic as an opportunity for increased cooperation, rather than an ultimatum. Chinese-led economic development, if carried out by conscientious stakeholders in countries with stable and responsible domestic governments, presents a valuable strategic opportunity for other countries. As both India and China look to strengthen their economic and political influence in the region, smaller states can use Chinese and Indian interests to secure more favorable investment and trade opportunities.

Moreover, China and India’s neighbors are strategically positioned to serve as a bridge for increased trade between the first- and second- largest potential markets in the world. For example, both China and India have committed to building railways to connect their countries to Nepal, with positive implications for the latter’s accessibility, along with trade, tourism, and energy. Though the case of Sri Lanka demonstrates the hazards of white elephant projects, which can result from poor management and overly ambitious investors, Nepal shows the potential for Chinese and Indian projects to complement each other. Once both railways projects are completed, Nepal will be able to facilitate trade and transportation between China and India. This and other connectivity projects represent a major opportunity for Nepal to benefit economically by encouraging greater cooperation between its two neighbors.

As lessons taken from Nepal and Sri Lanka go to show, countries looking to take advantage of Chinese funding should strike a balance between China and other potential investors, such as India, in order to maximize benefits from regional competition. Countries can use this economic competition to their advantage by focusing on financially viable projects that benefit their national interests, without leaning too heavily in any one direction.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: Maithripala Sirisena via Flickr

Image 2: Etienne Oliveau via Getty Images