Pakistan’s Ababeel: Neither a Surprise, Nor a Threat

By Rabia Akhtar

This week, Pakistan successfully conducted the first ever test of its new medium-range, surface-to-surface ballistic missile, which is capable of carrying multiple nuclear warheads. Pakistan’s testing of the Ababeel should neither come as a surprise nor should it be considered threatening to subcontinental strategic stability.

It is true to some extent that the nuclear spiral India and Pakistan are caught in is primarily driven by Sino-U.S. strategic competition. India maintains that its acquisition of anti-ballistic missile capability is China-centric and the same justification holds for Agni-V with the tested range of 5000 km. It is ironic that Indian advancements toward a triad are seen to have a stabilizing influence on the strategic dynamics in the region while Pakistan’s expansion towards a triad—such as Pakistan’s test of the Babur 3 submarine-launched cruise missile earlier this month—and survivability is seen as destabilizing rather than augmenting Pakistan’s deterrence.

There has hardly been any international reaction to the unrestrained Indian nuclear force modernization. India and Russia plan on jointly developing Brahmos cruise missile with a range of 600 km, which will cover entire Pakistan. This development took place soon after India joined the Missile Technology Control Regime last year, which prohibits its members from producing missiles beyond the range of 300 km, thus marking it to be a blatant violation in the making. One could argue that Indian nuclear and missile modernization does not appear to be threatening due to its declared no-first-use (NFU) posture in comparison to Pakistan. But Indian NFU is deceptive at best, and Pakistan does not have the luxury to take it at face value. Indian advancements towards a ballistic missile defense have given it a false sense of security coupled with an interest in a nuclear first strike against Pakistan. Given this, Ababeel provides Pakistan with a) a survivable force that will be able to absorb an Indian pre-emptive first strike and b) expansion of its targeting capabilities increasing both counterforce and countervalue targeting options.

Who holds power in Washington does not influence Pakistan’s strategic anxieties. Indian strategic advancements do, especially when they undermine Pakistan’s deterrence. While the Trump administration has yet to scope out its responses to Pakistan’s nuclear program and missile development, it is not likely to diverge from previous administrations. Strategic narratives do not change overnight and there is nothing that Pakistan can do that would make it any easier to deal with the new administration. Pakistan therefore needs to prioritize its own national interest and take whatever steps necessary to strengthen its deterrence vis-a-vis India. Babur 3 and Ababeel are such minimal yet qualitative measures that will provide Pakistan a robust strategic deterrence and restore strategic balance in the region.

Pakistan’s Ababeel: An Inevitable Development

By Hina Pandey

Two days before India’s show of military strength on its 68th Republic Day, Pakistan successfully tested its first surface-to-surface nuclear-capable ballistic missile. According to a press release by the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), the ballistic missile Ababeel has a maximum range of 2,200 km and the capability of delivering multiple warheads. This development is aimed at strengthening nuclear deterrence by adding an element of survivability to the nuclear arsenal.

The success of MIRV technology in Pakistan is significant for two reasons. First, it confirms the credibility of the various designs and technical parameters of Pakistan’s ballistic missile program. The country is already on the path towards qualitatively improving various aspects of its missile program such as warhead delivery and maneuverability. Thus, the development of MIRV technology is bound to instill confidence in Pakistani nuclear thinking. Second, the landmark development is a matter of pride for Pakistan. Only a few countries, such as the United States, China, and Russia, have been able to master this technology.

It is interesting to note the timing of the Ababeel test. Just two weeks ago, Pakistan conducted a successful test of the submarine-launched cruise missile Babur-3, which is meant to complete its nuclear triad. The test is the first step towards achieving this goal; the fully operational nuclear triad is only expected around 2030. Theoretically, Pakistan’s recent missile endeavors have been aimed at achieving two objectives: achieving a credible sea-based second strike capability, and strengthening its first strike credibility by increasing the likelihood of use.

In recent years, some Indian scholars have opined that the likelihood of a nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan is “infinitesimal and too remote to merit seriousness…near zero.”[1] Indian scholars have often doubted Pakistan’s capability of miniaturizing warheads and its intent to use tactical nuclear weapons (TNW) if this capability is achieved. In this context, recent developments can be viewed as Pakistan projecting its determination to develop its TNWs. However, the credibility of this signaling can only be assessed by the way in which it has been received by India. The Indian science community has already noted this development with a grain of salt. The head of India’s ballistic missile systems raised questions over the Ababeel test, claiming that it is challenging to use these technologies in a short range missile.

There are three possible ways in which the Ababeel test may pan out in the foreseeable future. First, Indian nuclear scholarship is likely to view this as an anticipated development in accordance with Pakistan’s efforts to counterbalance India’s conventional superiority. In this case, the development might be interpreted as providing “self-assurance.” Second, on the other end of the spectrum, this development may incentivize New Delhi to strengthen and assertively pursue its own MIRV option. Third, in light of the recent test, pertinent questions about the way in which the nuclear balance and perceived instability in the South Asian region have been altered are likely to take shape.

[1] Bharat Karnad, ( 2014) “Scaring Up Scenarios: An Introduction” in Ed. Gurmeet Kanwal and Monika Chansoria, (2014), “Pakistan’s Tactical Nuclear Weapons: Conflict Redux”, pp.2, 12

RIP Credible Minimum Deterrence

By Sadia Tasleem

January has been an eventful month. The inauguration of Donald Trump as the 45th President of the United States was followed by protests across the United States. The change of administrations conspicuously coincided with two notable developments in Pakistan. On January 9, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) announced the successful testing of a submarine-launched cruise missile, Babur-3. It was reported that the missile features “terrain-hugging and sea-skimming flight capabilities to evade hostile radars and air defenses.”

Two weeks later, this Tuesday, Pakistan reportedly tested another delivery system – this time Ababeel, a surface-to-surface missile capable of warheads using multiple independently-targetable re-entry vehicle (MIRV) technology.

A brief ISPR press release and a 30-second video of the test hardly reveal any information about the technical specification of the missile system. Also, the timetable of further testing and the plans about induction of the new system are not known. It is therefore difficult to offer a concrete analysis of the test and its significance. But what is important to ask is: Why MIRVs?

The ISPR press release contended that the Ababeel test was “aimed at ensuring survivability of Pakistan’s ballistic missiles in the growing regional Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) environment. This will further reinforce deterrence.” This generic description of the purpose behind development of Ababeel raises further questions. In the presence of land-based and sea-based cruise missiles that are also meant to evade detection and strengthen survivability, what additional value do MIRVs bring? What is meant by reinforcement of deterrence, and how will MIRVs strengthen it and at what cost?

These systems do not come for free. These are costly projects that require resources. However, given the lack of transparency regarding investment in sensitive technologies it is difficult to take the issue of ‘cost’ to a logical conclusion in Pakistan. Nonetheless, conventional wisdom suggests that maximizing response options and developing overkill capabilities do not yield any significant cost-effective dividends. What then perpetuates the notion of “the need to reinforce deterrence” by adding to existing capabilities? Toby Dalton and I argue elsewhere that the deterrence discourse in Pakistan heavily draws on the policies and literature produced in the United States during the Cold War era. Testing of MIRVs and Babur-3 only reinforce our conclusion that Pakistan seeks to emulate the United States without asking itself whether it should.

The trajectory of weaponization and missile testing in South Asia over the last few years had already undermined the notion of credible minimum deterrence, Pakistan’s stated nuclear doctrine. The introduction of MIRVs and Babur-3 would likely increase Pakistan’s fissile material requirements as well as intensify the already existing nuclear competition between India and Pakistan. The death of credible minimum deterrence is therefore imminent.

The Myth of Pakistani MIRVs

By Sitakanta Mishra

According to an official press release, Pakistan’s first successful flight test of a surface to surface ballistic missile Ababeel is capable of “defeating the enemy’s hostile radars” and “aimed at ensuring survivability of Pakistan’s ballistic missiles in the growing regional ballistic missile defence (BMD) environment.” The press release demonstrates a miscalculation within Pakistan that it has reinforced nuclear deterrence vis-à-vis India. While many view the flight test as altering strategic dynamics in the region, Pakistan has a long way to go to achieve full operationalization of its multiple independently-targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) missile force, an effort that would require copious amounts of resources. Thus, the effect of Pakistan’s newfound capability on regional stability should not be overstated.

As the MIRV race has begun, consequent speculations about its impact on stability, first-strike/second-strike capabilities, viability of the strategic triad, and the “arms race or strategic restraint” debate will be core questions in the South Asian nuclear discourse for decades to come. Intriguing is the impetus it would provide for future multiple interceptor missile (MIM) programs. This may not be so lucrative for India given its vast strategic depth. However, Pakistan’s lack of strategic depth and desire to attain “full spectrum deterrence” may push it to pursue an MIM program in the future, especially given its focus on survivability.

However, Pakistan has a long way to go to achieve full operationalization of its MIRV missile force. In order to master the technology and achieve the necessary payloads in the absence of Chinese assistance, Pakistan would need to divert resources away from other critical areas of its economy. This would especially be so in order to compete with or respond to India’s future technological pursuits like cruise missile defense (CMD) and anti-satellite capability. Islamabad should have learned from the Cold War MIRV discourse: while the MIRV may be a technologically-savvy weapons system, it didn’t really upset the Cold War balance. To deter India, development and growth in other areas would be a more effective strategy for Pakistan.

Though many would argue that Pakistani’s MIRV capability is bound to change the strategic threat dynamics in South Asia, Pakistan’s technological claims should be taken with a grain of salt. Doubts exist about whether MIRV technology can be used in a medium or short-range missile. Also, to penetrate an anti-missile defended area, a MIRV attack strategy can only succeed by firing a larger number of missiles to ensure that at least one of the warheads reaches the target. In this sense, MIRV “acts as a penetration aid” only and the technology of independent targeting is unnecessary. The task of exhausting anti-ballistic missile defense can be accomplished by less complex systems like multiple-warhead missiles or multiple re-entry vehicles (MRV). Finally, high accuracy is essential in order to master a MIRV capability, which Pakistan lacks at present. Pakistan largely depends on the Chinese GPS satellite system Beidou, which is not sufficient for neutralizing the silos scattered across India’s territory.

Islamabad has achieved the dubious status of having one of the fastest growing nuclear arsenals in the world. With a MIRV program, Pakistan will invest heavily in the production of warheads and fissile materials, which will increase the size of its nuclear arsenal even further. However, unless there is still a clandestine procurement channel operating, obtaining the necessary nuclear fuel will be a challenge when Pakistan’s own reserves are meager and open sourcing is difficult.

***

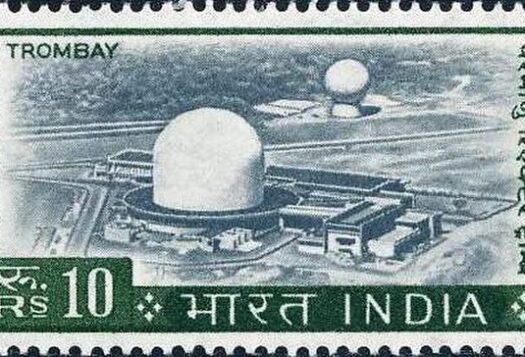

Image: ISPR