Over the last decade, the Indian higher education landscape has seen rapid privatization across states, owing to the rise of “edupreneurs” who are engaged in providing education through private financing and promoting a nonprofit public-private model. While the privatization of higher education helps in offering a larger number of disciplines to potential students, it presents a few structural problems with regard to efficiency and equity.

Efficiency here means the quality of educational services measured by employability of the skills developed through that education, while equity is about access to higher education to those interested in pursuing it. Due to the lack of public investment in an affordable, quality higher education system that is accessible to all, often private institutions can only provide services to those who can pay certain fees. This creates higher excludability and rivalry among those who are willing to seek higher education, increasing elitism in its distributional system, and thereby, generating equity concerns. Here we discuss how a blend of public and private higher education institutions is crucial for balancing the trade-offs of equity and efficiency.

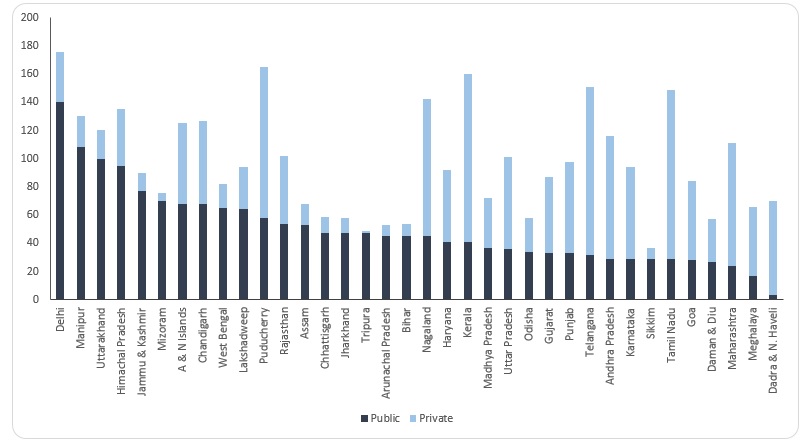

Figure 1 shows that most states with higher per capita incomes and higher private investment in education (such as Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Gujarat) have more students registered in private institutions, while most states with lower per capita incomes and lack of private investment in higher education are largely dependent on public institutions.

Figure 1: Per 1000 Distribution of Students by Type of Higher Education Institution

Source: NSSO 71st Survey Round (2014); States/Union Territories have been arranged in decreasing order of distribution of students in public institutions

Given this information, it is likely that there are vast differences in the quality and accessibility of higher education provided across India, which raises both efficiency and equity concerns. But knowledge should be rendered without excluding anyone and without creating competition among consumers. In states where private institutions are dominant, only a limited number of students have access to education, based on their ability to pay the necessary fees. However, it is possible to develop a robustly-planned and implementable goal-based higher education policy framework that builds on the content of higher education while optimizing both efficiency and equity.

Towards a Goal-Based Higher Education Policy Framework

In the current context of the marketization of higher education, both educational institutions and the state can gain from a goal-based objective framework by considering some of the following suggestions.

First, the state should ensure a policy of egalitarianism in the selection process for students and faculty members in both public and private institutions. According to American economist Kenneth J. Arrow, an imperfect selection of students may arise out of “deliberate attempts to control access to the university by the institution itself.” A studentship-based university acceptance scheme could be introduced where students can pay the full cost of their education in a time-bound period (say, within 3-4 years after completing their studies). The amount a student pays may proportionally depend on the income earned. Such a studentship model will require much deliberation and needs to factor various socio-economic considerations such as the financial background of the student, degree course undertaken, employment opportunities available after the degree, and wage levels. However, such a scheme seems vital to ensuring efficiency while remaining mindful of equity considerations.

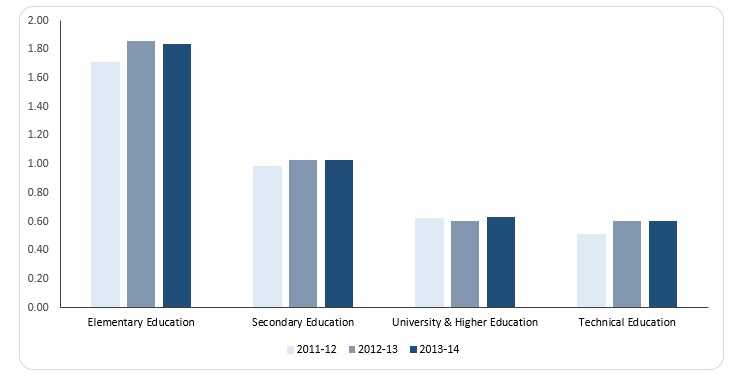

Figure 2: Public Revenue Expenditure on Types of Education (% of Gross Domestic Product)

Source: Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India

Second, states should expand their role in funding studentships (particularly in existing public institutions). Figure 2 above displays the lower share of public expenditure on higher education as compared to other levels. The state plays a vital role in developing what Arrow has called the “ethos of social stewardship” among students while keeping the “plurality of social values” and society’s future in mind. In the Indian scenario, this has been a missing link in the state’s support to higher education. The lag seen in the socio-economic performance of skill development and employability of existing human capital across sectors in India is causally linked with the disproportionate access to quality higher education in India.

There is no doubt that dealing with problems of efficiency and equity in improving content and quality of higher education is a complex subject of discussion and requires long-term policy planning. The Indian government has had an indifferent approach to reforming the higher education landscape. However, in pursuit of academic excellence built on inculcating constitutionally-recognized principles of democratic accountability, public reasoning, and impartial critical scrutiny, an urgent dialogue is needed in reinventing the wheel of higher education services.

***