Can India be a meaningful partner of the United States in global governance? Many in the United States have regularly raised this question as both a practical and a strategic problem since 2000. At the practical level, the incongruence between both countries’ understanding of world affairs started becoming a low-cost irritant to an otherwise flourishing bilateral relationship. At the strategic level, the United States’ stakes in India have been steadily increasing – it has invested strategically in India as a counterbalance to China, installed it in the nuclear order, and prepared to support New Delhi’s bid to join the global high table in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) when the time comes. Assessing India’s future role in the international order and gauging its behavior against Washington’s interests remain a necessity for the United States.

For the last 20 years, the United States has mostly overlooked its divergences with India in multilateral forums as the relationship paid economic, strategic, and political dividends bilaterally, whereas the costs of divergences at the multilateral level were negligible. In spite of such exceptionalism enjoyed by New Delhi, U.S. diplomats at all levels reminded their Indian counterparts that India’s “obstinate role [at the UN] was increasingly at odds with our emerging strategic proximity.” With a restructuring of the global order, continuous assault on rules-based order, and China’s rise as a common strategic adversary, the costs of their inability to work together in the global governance arena can be much higher for both countries today. This policy memo addresses this often-underexplored aspect of the India-U.S. relationship. The memo is divided into three sections. Part one outlines and quantifies the problem, followed by part two that discusses legacy issues and new trendlines and part three that concludes the piece and presents policy recommendations for both countries.

Part I: Research Question and Methodology

This memo attempts to answer the question of why the United States and India are at odds in multilateral forums despite their growing strategic proximity since 2000. In answering the question, I take the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voting convergence as a primary indicator, while also following instances of both countries’ interaction at various UN-led organizations, including the UNSC, where India served once during 2011-12 as an elected member. Since many of the UNGA resolutions are by consensus and not all carry equal emphasis, those marked as “important” by the State Department are privileged here. Apart from statistics, the memo is informed by interviews with over a dozen Indian and U.S. diplomats, including former ambassadors, former permanent representatives and their advisors, and those who have served in respective bureaus in both countries. The memo limits itself to political issues in international organizations, excluding the trade and financial domain, which have their own dynamics.

With a restructuring of the global order, continuous assault on rules-based order, and China’s rise as a common strategic adversary, the costs of [India and the United States’] inability to work together in the global governance arena can be much higher for both countries today.

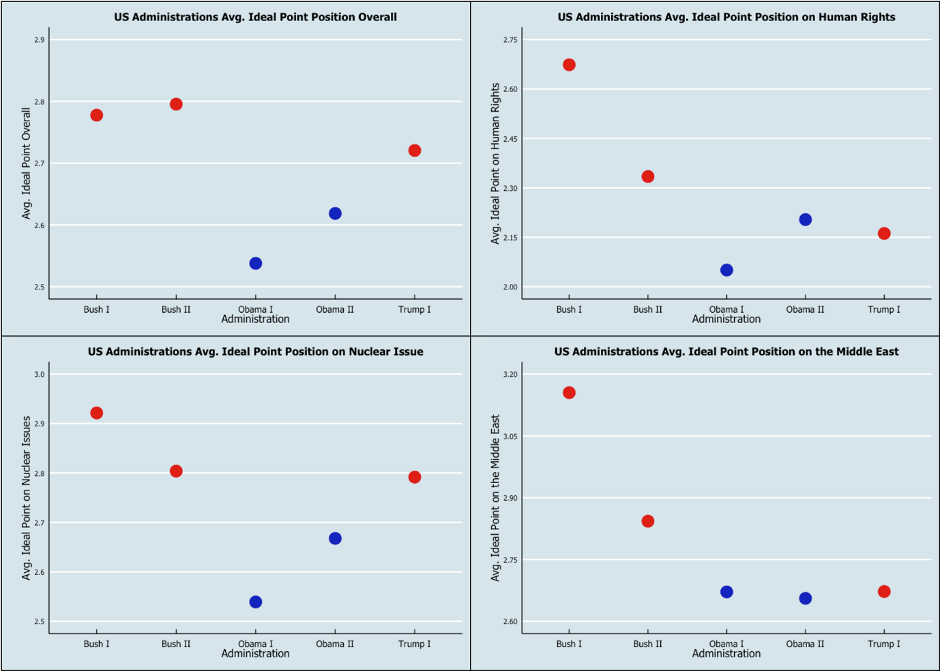

This research is not driven by a hegemonic understanding of interstate dynamics in which nations closer to a superpower must follow the superpower’s positions multilaterally. Instead, it sees the Indian case as counterintuitive because, generally, plural democracies with a free-market economy, the rule of law, and strategic proximity with the United States tend to make choices similar to the United States on global issues. In other words, democracies that have assimilated themselves in the U.S.-led liberal international order do not tend to diverge much as they share common values and principles. Yet, India does diverge. Two crucial caveats are necessary here: 1) the U.S. positions are not always static 2) nor are they normatively desirable to be followed. The U.S. positions on global issues can vary dramatically between and within administrations. Figure I indicates the average policy position taken by a U.S. administration over four years1 on different issues, therefore showing policy fluidity. An extreme example is the Trump administration’s decision to declare Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, a position which some of its closest allies like Canada could not unequivocally endorse at the UNGA.2. On the normative front, the United States did not join a near-unanimous UNGA resolution declaring the COVID-19 vaccine as a global good, perhaps to protect the interests of its pharmaceutical industry.

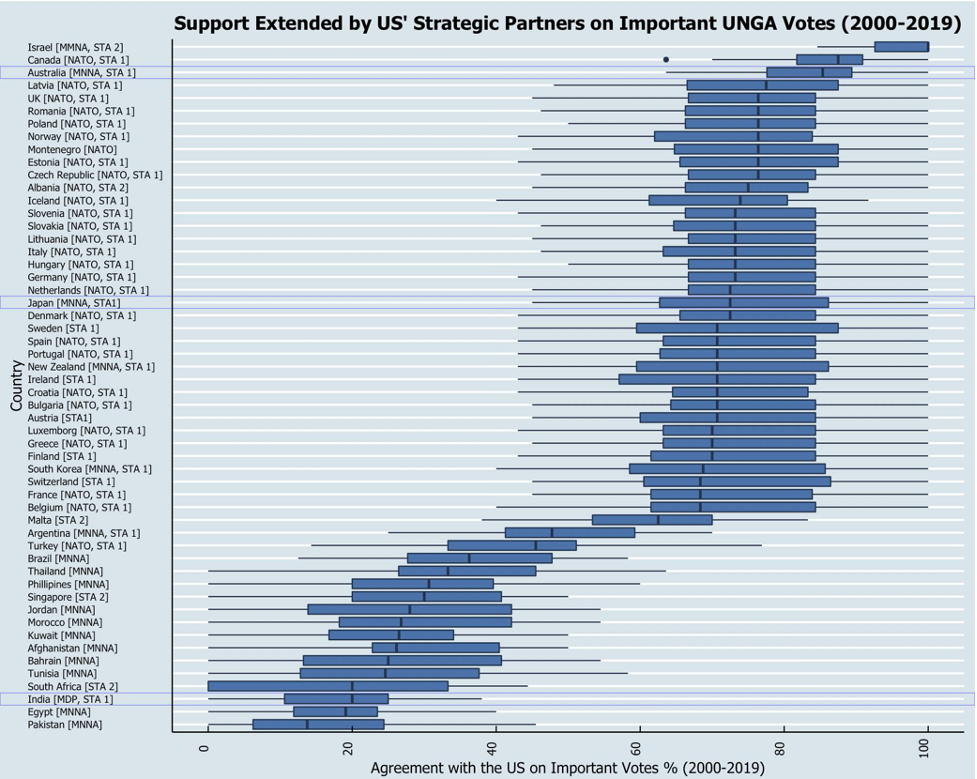

As Teresita Schaffer, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South Asia, once indicated, “[it is] conventional wisdom that the United States and India can work together bilaterally, but not multilaterally.”3 While the India-U.S. differences multilaterally are widely accepted in U.S. policy and academic circles, rarely has that gap been quantified. The following graph measures India’s support to the United States on all “important” UNGA resolutions between 2000-2019 and contextualizes it by identifying India’s position among all its strategic partners.4

Statistically speaking, India’s numbers are only slightly better than Pakistan and Egypt, both countries that can hardly boast any trade, defense, or strategic ties with the United States when compared to India. To put the numbers in context, both Japan and Australia – the two other members of the Quad along with the United States and India – have aligned 80 percent with the United States while India’s alignment stands dismally at about 20 percent. In broader terms, India is not only a friendly outlier for the United States, its positions are an aberration to the future coalition of democracies who are willing to work together multilaterally.

This does not mean India is anti-democratic per se; numbers conceal more than they reveal. India remains a deviant case due to its postcolonial history, great power politics in the region, particular approach towards multilateralism, its future UNSC ambitions, and the comfort it wants to enjoy with both the Global North and South in its new, confident role as a major economy. The following section reviews how India’s past and present have impacted its multilateral outlook – an outlook that is seemingly at odds with its democratic credentials, free market stance, and strategic proximity with the United States and other Western democracies.

Part II: Understanding Indian Divergences and Convergences

This section outlines why India has remained at odds with the United States by analyzing India’s positions from three perspectives: 1) Indian decision-making, 2) thematic choices, and 3) country-specific positions. The final part of this section highlights emerging trends in the India-U.S. relationship.

Indian Decision-Making

Since the early 1990s, India has made its UNSC permanent seat ambition abundantly clear. Over time, New Delhi has worked aggressively towards this end. Indian decision-makers understand that on the judgment day of UNSC reform, it needs the goodwill of as many blocs and constituencies as possible. Any reform process would need concurrence of the UNGA, where the principle of “one state, one vote” applies. Hence, India’s once practiced policy of non-alignment has transformed into a policy of non-alienation, which requires it to not alienate any major bloc, group, or constituency in international forums. Given the number game between two constituencies of varying size, India would be swayed by size. Therefore, partly due to historical reasons and partly due to numbers, India is often seen aligning with developing countries including non-alignment movement (NAM) countries and the G77 against the much smaller western bloc, even when such Third Worldism is disparaged back home.5 India’s once practiced policy of non-alignment has transformed into a policy of non-alienation, which requires it to not alienate any major bloc, group, or constituency in international forums.

The second thread in Indian thinking is that if India’s vote is not going to change the outcome, it is better to abstain than alienate by voting with the minority. Thus, India is notoriously known for abstentions, a policy that is often criticized domestically as being too risk averse. Third, until India does secure a position at the global high table, it wants as many issues as possible to be dealt with at the UNGA level, where it can assert its leadership. Thus, it resists any attempts by P5 countries to increase the remit of the UNSC or the Secretary General. Fourth, Indian strategic thinkers hanker for a multipolar world, meaning India would not lean towards any one country on all issues. Fifth, in the previous decade of 2000s, many Indian diplomats were dogmatically imbued with an outlook of non-alignment and strategic autonomy, which diplomatically manifested itself as a certain frigid approach towards the United States, regardless of the warmth between political classes. In the last few years and even today, this is hardly the case.

Thematic choices

India’s divergence with the United States remains a function of particular thematic choices it has made in international affairs. On nuclear weapons disarmament resolutions, for instance, India votes against resolutions pressing for treaties such as the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) or Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), to which it remains a non-signatory. Instead, India presses for total and non-discriminatory elimination of nuclear weapons through two annual resolutions – “Reducing Nuclear Danger” and “Convention on the Prohibition of the Use of Nuclear Weapons” – which is met with stiff opposition from the P5, including the United States and its allies. The difference on conventional weapons is less stark. On economic issues, India mostly sides with the Global South on trade liberalization, debt relief, development assistance, global economic and financial governance, and sustainable development, among others.

Another important sticking point is regarding human rights. Indian diplomats privately comment on the U.S. approach as “finger pointing” and “name and shame” to which India does not readily agree to. India’s reservations are threefold. First, India has been at the receiving end because of the management of secessionist movements within its territory. India feels that, sometimes, the western world may not be sensitive enough to challenges faced by others in managing such movements. Second, India sees human rights resolutions as a precursor to regime change operations, which then become a theater for great power politics (e.g., Syria or Libya).6 Finally, there is a fundamental difference in approach: the U.S. side believes naming someone brings them to the negotiation table, while the Indian side thinks that name-calling should be the last resort.

There are still other legacy issues, such as decolonization, UN administration, having a larger say in peacekeeping operations, and powers of the Secretary General, among others, where India and the United States have differed historically and continue to do so.

Country-Specific Positions

Apart from thematic choices, India, like any other country, has to take sides between feuding countries at the UN. On the enduring issue of Israel-Palestine, where the United States unwaveringly supports Israel, India has leaned towards the Palestinian cause because of its energy dependency on the Arab world and significant Muslim population at home. More recently, India has occasionally taken the Israeli side to indicate flexibility, signal some sort of equanimity to Tel Aviv, and most importantly, perhaps hint to the Arab world that India’s support to Palestine is dependent on their reciprocal support on Kashmir.

Another set of country-specific issues are those where the United States and Russia are in direct contestation. Russia has been the top supplier of critical arms and ammunitions to India, as well as a consistent veto provider in the UNSC when the United States was still balancing between India and Pakistan. India’s dilemma of choosing between a historical relationship (Russia) and an emerging relationship (United States) became more acute during its 2011-12 stint as a non-permanent member of the UNSC, especially when it came to cases like Syria. However, in the past few years, India has mostly chosen to abstain from such situations, which sometimes means extending vocal support to the Russian cause so as to not ruffle feathers in Moscow. For example, on Crimea, New Delhi abstained on UNGA Resolution 68/262, which Russia lost, and eschewed taking sides despite agreeing in principle with “legitimate Russian interests.” It similarly abstained from an Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) vote by Russia, which proposed a new investigation into the death of ex-spy Sergei Skripal – a vote Moscow lost in part due to 17 abstentions.

Russia has been the top supplier of critical arms and ammunitions to India, as well as a consistent veto provider in the UNSC when the United States was still balancing between India and Pakistan.

India’s voting patterns have also been more consistent with China’s than with the United States’. Both China and India want to be on the side of the developing world and, sometimes, India accommodates China in the hopes of calm northeastern borders. However, China has not been a major friction point so far.

There are still other countries that India cannot condemn unequivocally or has to choose their side for one reason or the other. For example, what India has called the “three problem children”– Myanmar, Sudan, and Iran – are the ones that remain unfavorable to the United States for human rights or nuclear issues. India has to consider energy supplies with Iran and Sudan. With Myanmar, it has to consider its historical ties. On Iran, the United States wants India’s support at the IAEA, which it receives occasionally. Within its neighborhood, India has to take sides as a reliable friend if a country is ever at odds with the United States, such as with Mauritius in the Diego Garcia case wherein Mauritian sovereignty clashed with the U.S. interest of an Indian ocean base.

An Ally-in-Making

It would be remiss to only portray the U.S.-India relationship as adversarial. Both sides have actively cooperated on many issues due to India’s changing outlook on global affairs, emerging geopolitical necessities, or simply to meet the United States’ expectations. For example, on climate change, India gave up its past objections and cooperated with the United States and other western powers during the Paris Agreement negotiations. Since then, India has not only been at the forefront of meeting its annual targets but has also demonstrated leadership of sunshine countries by instituting the International Solar Alliance. Similarly, emerging threats from a common adversary, like China, compels both countries to work together, as was seen in the combined efforts of India, United States, and EU diplomats who tried to prevent “Xi Jinping thought” from infiltrating UN resolutions. Finally, at times, India understands that it has to find flexibility in some areas to make up for some of the positions where it cannot give in to the United States’ demands for the sake of bilateral relationship.

Part III: Policy Recommendations

For active cooperation between both countries and to meet emerging mutual challenges in multilateral settings, the following policy recommendations are suggested:

Establish an annual US-India Multilateral Dialogue

There is a consistent lack of regular exchanges to discuss issues in multilateral governance. As both governments decided to move forward with their relationship in the early 2000s, a “Global Issues Dialogue” was established in 2002 to sort out mutual differences in multilateral governance. The dialogue continued intermittently for a few years, but it has not been a focus area for either country. A similar, upgraded dialogue (the “U.S.-India Dialogue on UN and Multilateral Issues”) was conducted in February 2015. As the Trump administration’s interest in the UN faded, the subsequent two iterations happened at much more junior level.7

An annual dialogue can take place a few months before the beginning of General Assembly session in September to identify common interests involving members from respective bureaus and representatives from New York and Geneva. With the potential expansion of Quad into non-military areas, this practice can add Australia and Japan in future to address common set of issues.

Usually, it is a U.S. practice to reach out to like-minded countries before the General Assembly session commences for their cooperation. Those countries, in return, make their own demands. It ends up as an exchange of wish lists from both countries for the upcoming session. This tactical exchange, in the case of India, can be broadened to identify mutual interests in a range of organizations where bilateral interests coincide. As one diplomat illustrated, India and the United States are working closely on Information and Communications Technology (ICT), but both countries have never come together to discuss how they can work together at the International Telecommunication Union, a specialized ICT body of the UN. An annual dialogue can serve two purposes: first, to iron out existing differences on issues and modalities to achieve them and, second, to proactively chart out a mid- to long-term vision based on mutual interests.

Build a Coalition of Like-Minded Countries

Building a common vision avails both countries the opportunity to build a coalition of like-minded countries who identify the same goals and are willing to share responsibilities. Sometimes, such a coalition building is an imperative rather than a choice. For example, to counter any move that is not in either India or the United States’ interest in the NAM group, at least two countries should object to prevent a resolution from moving ahead. Here, India would need the support of other countries. In particular, when there is a resolution in support of China’s position, India would want to lead from behind rather than entangle itself directly given existing frosty ties between China and India. Here, support of pro-Taiwan nations who are a part of NAM can be helpful.

An annual dialogue can take place a few months before the beginning of General Assembly session in September to identify common interests involving members from respective bureaus and representatives from New York and Geneva. With the potential expansion of Quad into non-military areas, this practice can add Australia and Japan in future to address common set of issues.

Analyze and Arrange Priorities

For the U.S. side, it is important to calibrate its expectations with India. Certain positions India takes are non-negotiable and do not immediately harm U.S. interests. A productive strategy would be to classify issues in a matrix of negotiable/non-negotiable from the Indian side against those priority/non-priority for the U.S. side. Those issues that fall in negotiable and priority category would be low-hanging fruits that can immediately enhance cooperation.

Addressing India’s UNSC Ambitions

A crucial issue between both sides has been the U.S.’ support for India’s bid to a permanent UNSC seat. Indian diplomats begrudgingly refer to the U.S. presidential endorsements as “insincere” as they are limited to only bilateral statements. Unlike Russia, France, and the UK, the United States has never endorsed India within the UN. Indian diplomats who have worked at the UN believe this makes it difficult for them to advance their collective cause, especially while working with third countries. For the U.S. side, endorsing India’s bid and not extending a similar courtesy to Japan and Germany can spark dissatisfaction. Although it sounds like a small irritant, this not only adds a practical challenge, but also fuels discontent on the Indian side. To put an end to this difference, perhaps the U.S. Permanent Representative can tacitly endorse Indian bid at the UN by referring to bilateral statements. This step can boost both sides trust and willingness to work together.

Benefitting From India’s Leadership Bid

India attaches great value to multilateral issues where it can assert its leadership. New Delhi’s taking up the issue of solar energy and becoming a bridge between the developing and the developed world in terms of finance and technology to mitigate climate change is a key example. Rather than considering India’s leadership ambition of the developing world as a red mark against it, the United States should take advantage of India’s goodwill with the Global South under a mutually agreed-upon strategy to mitigate the existing divide.

Through many milestones in difficult domains, such as strategic and nuclear, both countries have demonstrated that they can overcome their differences if they are willing to. The same will can be extended to global governance for mutual benefits and to meet future challenges.

Stimson South Asia Program Visiting Fellows represent a diversity of perspectives and experience. As members of a term academic program, their writing and views do not necessarily represent those of the South Asia program or of the Stimson Center.

Editor’s Note: This piece is part of a collection of policy memos published by South Asian Voices Visiting Fellows and was originally published on the Stimson Center website in April 2021. The Visiting Fellowship is a year long fellowship that combines professional development of research, writing, and public speaking skills with extensive exposure to the D.C. policy community. More information on the South Asian Voices Visiting Fellowship is available here.

***

Image 1: Tom Page via Wikimedia Commons

- ]“Average policy position” is a unidimensional ideal point that marks state preference in a policy space. It is extracted from roll call data using Item Response Theory (IRT) algorithms. For details see: Bailey MA, Strezhnev A, Voeten E, “Estimating Dynamic State Preferences from United Nations Voting Data,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61, no. 2, (2017): 430-456. The Trump 1 period includes the first three years of his presidency.

- Canada abstained from UNGA resolution ES-10/L.22

- Teresita C. Schaffer, “The United States, India, and Global Governance: Can They Work Together?”, The Washington Quarterly 32, no. 3, (2009): 79.

- Strategic partners are defined as NATO allies, Major Non-NATO Allies (MNNA), Major Defense Partner (MDP), and countries with STA-1 and STA-2 authorizations.

- For a sample critique of India’s Third Worldism, see C Raja Mohan, Crossing the Rubicon: The Shaping of India’s New Foreign Policy. (New Delhi: Viking India, 2003).

- In the UN parlance, the issue falls under the rubric of Responsibility to Protect (R2P). Former Indian Permanent Representative and current cabinet minister, Hardeep Singh Puri’s book Perilous Interventions (2016: New Delhi, Harper Collins) covers India’s views on the principle and individual cases.

- There have been no public announcements of later two iterations since 2015.