The year 2017 was a grim one for India-China ties. The Doklam standoff, Beijing’s repeated move to block India’s request for the declaration of Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) chief Masood Azhar as a global terrorist at the United Nations, and China’s lack of support for India’s Nuclear Supplier’s Group (NSG) membership bid sullied relations. However, the year ended on a positive note with the visit of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to New Delhi followed by the 20th round of border talks between National Security Adviser Ajit Doval and Chinese State Councillor Yang Jiechi, with both sides recognizing the importance of stronger India-China relations and maintaining peace at the border.

This flurry of diplomatic activity continued into 2018, with not only a focus on mitigating security issues but also addressing economic impediments in the relationship. At the recently concluded 11th session of the India-China Joint Group on Economic Relations, Trade, Science and Technology, the two countries explored ways to enhance development of bilateral trade and investment cooperation, touching upon ways to reduce their trade imbalance and potentially starting negotiations on a Free Trade Agreement (FTA). Indian and Chinese representatives also participated in the fifth iteration of the bilateral Strategic Economic Dialogue to discuss ways to further their economic engagement and clear any obstacles in doing so. These developments are testament to the fact that despite security and geopolitical concerns, there is recognition in both countries that there is potential for and mutual benefit in making India-China economic cooperation more robust.

Imbalance and Protectionism Belie Trade Potential

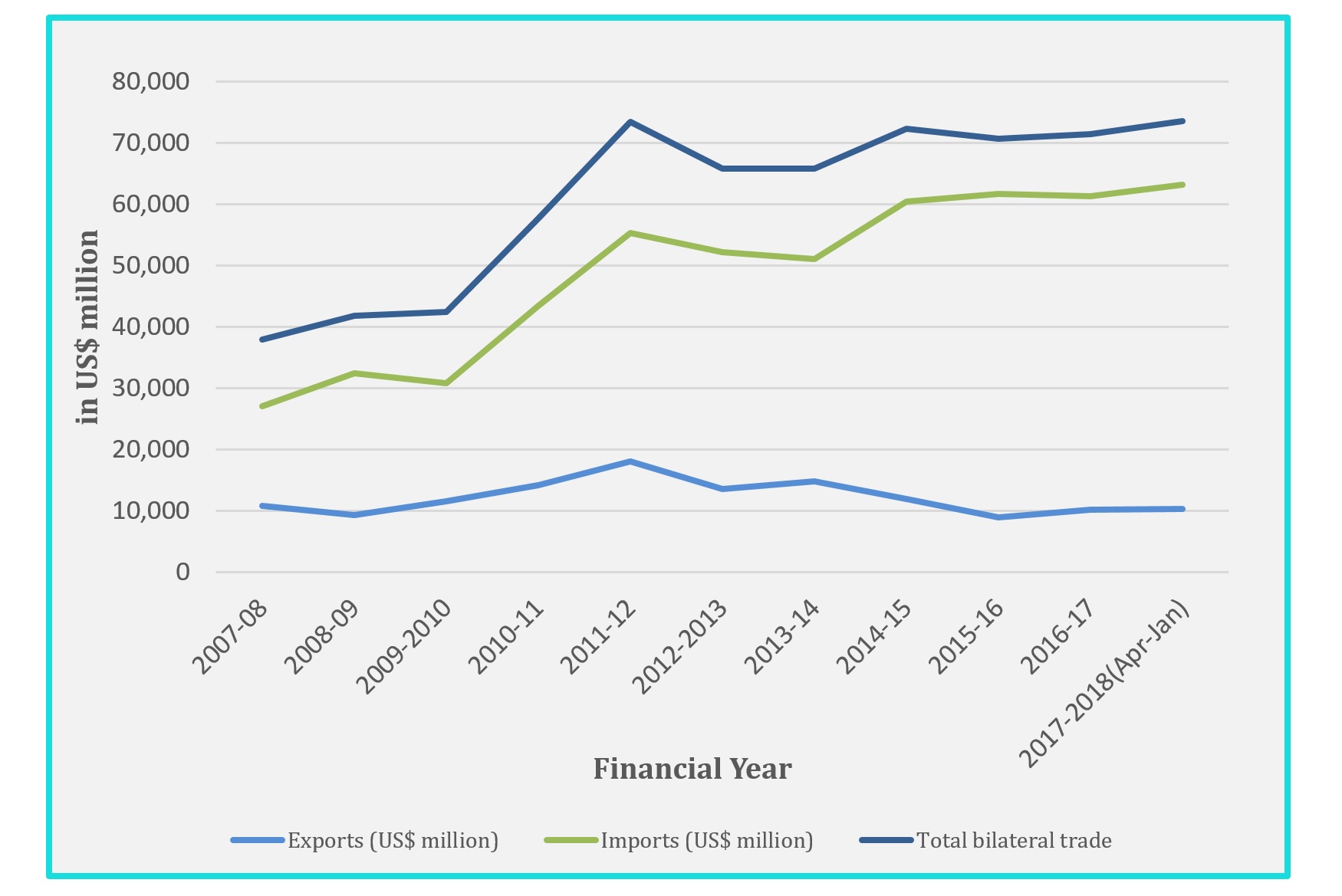

According to data from the Indian government, India-China bilateral trade has grown from $38.02 billion USD to $71.45 billion USD over the past decade (refer Figure 1 below). There were jumps in 2011-2012 and 2014-15, mainly due to an increase in Chinese exports to India, but trade has been somewhat stagnant in recent years.

Figure 1: India’s Total Bilateral Trade with China and Indian Exports to and Imports from China (in US$ million)

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India

From New Delhi’s perspective, a significant trade imbalance in favor of China, market access issues, and security considerations have kept bilateral trade limited. A trade deficit of $51.11 billion USD with China is a cause for concern for New Delhi because it signifies an inability to compete with Chinese manufactured goods. Chinese exports to India include manufactured goods such as electrical machinery and power equipment while Indian exports comprise mainly of resource-based items such as iron ore and cotton. Indian manufacturing still has a long way to go before India can move up the value chain with respect to its exports to China.

Strengthening their economic relationship can confer significant gains upon both nations. China’s vast size, its growing middle class, and its bid to move towards a domestic consumption-based economy mean its offers great potential as a future market for Indian goods and services as well as a source of greater investments.

Additionally, Beijing’s protectionist policies hinder the ability of Indian companies to enter Chinese markets. New Delhi has been pushing China to open up its market to Indian IT, pharmaceuticals, and agri-products, as well as for increased Chinese investments to reduce their trade deficit. Even in sectors where India has a competitive advantage, such as pharmaceuticals where India accounts for 20 percent of global generic medication production, Indian firms find it difficult to enter Chinese markets. Indian pharmaceutical firms that already have a presence in China complain about a lack of market access and overly restrictive regulatory procedures, which New Delhi has continually addressed with Beijing, to little avail. However, any retaliatory move on India’s part to restrict the import of Chinese goods will be detrimental, Indian manufacturing depends on cheap Chinese imports in the form of electronics and IT products.

Bilateral Investment: A Silver Lining

While the two countries have had myriad issues related to economic investment in the past, they have begun to address these hurdles in recent years. In 2014, China announced an investment of $20 billion USD in India over the next five years, such as in industrial park projects in Gujarat, Haryana, and Maharashtra. This investment was expected to scale up India’s manufacturing capabilities and assist India in reducing its trade deficit with China. However, some of these projects have moved slowly due to land acquisition challenges. China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) into India between April 2000 and June 2017 stood at $1.67 billion USD, which is only 0.49 percent of the total FDI inflows into India over the same period. Still, India’s continued emphasis on greater Chinese investment in manufacturing has yielded some results—60 percent of Chinese FDI into India from April 2000 to September 2015 went into automobile manufacturing and smartphone company Xiaomi will soon have up to five manufacturing plants in India.

The success story though has been significant private investment from China in Indian start-ups, especially those focused on technology and e-commerce. In 2017 alone, Chinese companies such as Alibaba, Fosun, Baidu, and Tencent put in $5.2 billion USD into 30 Indian start-ups. Chinese conglomerate Alibaba and its affiliates alone have invested about $1.7 billion USD in Indian start-ups such as Paytm and BigBasket.

Rationale for Stronger Economic Ties

Strengthening the India-China economic relationship can confer significant gains upon both nations. China’s vast size, its growing middle class, and its bid to move towards a domestic consumption-based economy mean its offers great potential as a future market for Indian goods and services as well as a source of greater investments.

In positive news, bilateral trade in 2017 reached an all-time high of $84.44 billion USD, according to Chinese figures. In addition, Chinese companies have shown keen interest in investing in India, pledging about $85 billion in projects at a trade event last year. Overall, a stronger India-China economic relationship can be beneficial for both countries, especially considering that India plans to strengthen its industrial sector and China plans to move up the value chain with respect to its manufacturing sector. In this respect, investment by China in Indian firms provides them with much-needed capital to scale up their capabilities while China gains greater technological skills, especially considering India’s comparative advantage in sectors such as IT as well as other legal, consulting, and marketing services.

But challenges such as trade imbalance, market access issues, and a restrictive regulatory environment need to be addressed. More importantly, geopolitical circumstances will continue to pit India against China, which can impact economic opportunities for New Delhi—an example is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, setting aside differences, New Delhi can very well enhance economic cooperation with Beijing, as suggested during Chinese Commerce Minister Zhong Shan’s recent visit to New Delhi, to promote its own interests through more Indian exports to China, and larger presence of Indian businesses in China. India can also consider selective targeting with respect to China’s BRI, allowing Indian companies to bid for projects that are open to international bidding.

Editor’s note: After months of tension due to the Doklam standoff, there has been a thaw in India-China relations recently, with Indian Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj and Indian Defense Minister Nirmala Sitharaman visiting China over the next few days to get the relationship back on an even keel. However, many irritants in the relationship remain. In this series, SAV contributors assess the status of India-China competition in the post-Doklam era–whether it is heating up or cooling down–and how it manifests itself, with regard to security, economics, and politics. Read the rest of the series here.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image: Embassy of India, Beijing