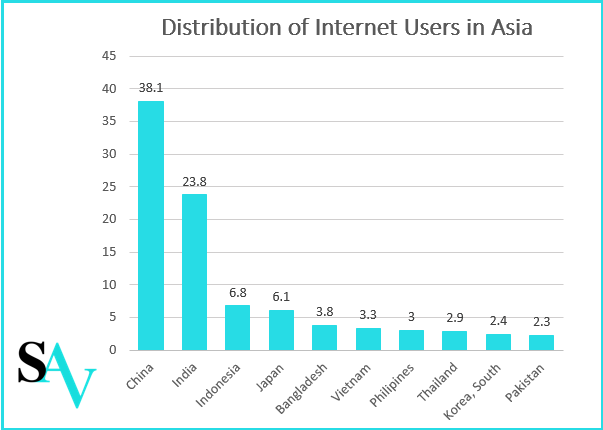

South Asia has attracted attention for the subconventional, conventional, and nuclear rivalry between India and Pakistan. Cyberspace, while increasingly regarded as a conflict theater by analysts, has not garnered the same attention from researchers focusing on South Asian security issues, perhaps because its potential for violence is largely intangible when compared to hand-to-hand combat or even asymmetric warfare. In the case of India, a cursory look at internet penetration (460 million internet users in 2017) is an indication of the high level of traffic that information technology and related services can generate.

With such widespread usage of the internet, cyberspace has its own set of vulnerabilities, which form a threat spectrum comprising ranging from acts of cyber-vandalism (i.e. when an individual or group takes control of a website and defaces it) to cyber-radicalism (such as extremist groups using the web to spread propaganda, incite violence, and plan and carry out potentially catastrophic attacks). The rapidly evolving nature of cyber threats presents unanticipated challenges to India’s security from state-affiliated and non-state actors. Such dangers have potentially nightmarish consequences for South Asia, as a cyber attack on India’s nuclear and conventional arsenals could potentially undermine the deterrence stability in the region.

Source: Figures for June 2017 by Statistica

Nature of Cyber Threats and Vulnerabilities

Cyberspace is not bound by physical or national boundaries. Geography or political divisions do not apply to global cyberspace, where disruptive changes at one end of the spectrum can reverberate throughout the system. This interconnectivity means India is vulnerable even to cyber attacks not directly aimed at India: in the case of the WannaCry ransomware attack in 2017, which infected more than 300,000 computers in 150 countries and was attributed to hacking group Lazarus acting on behalf of the North Korean government, India was the third worst-hit nation with approximately 48,000 computers infected. Prior to this, the 2010 Stuxnet malware attack that targeted Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition Systems (SCADA) systems or industrial control hardware, which many have attributed to state actors, was responsible for attacking Iranian nuclear centrifuges and also infected about 10,000 computers in India. Fifteen of these computers belonged to critical infrastructure facilities, including the electricity boards of Gujarat and Haryana as well as an Oil and Natural Gas Corporation offshore oil rig. Further, by the Nuclear Power Corporation of India’s own admission, they block at least ten targeted cyber attacks a day. These instances illustrate that the boundless nature of cyberspace presents challenges in defending critical state assets, since threats emerge from both cyber attacks targeted at India and external cyber attacks not directly involving India.

The anarchic nature of global cyberspace—with no spearheading institution to confront or manage conflicts—provides little incentive to refrain from such attacks, as the threat of being caught and physically retaliated against is muted.

Another dimension of the threats facing India from the cyber domain is the ease with which numerous actors can carry out or authorize such attacks. The non-physical nature of cyberspace means geographic location is no longer a barrier to inflicting damage upon a state; a range of actors may operate remotely to deface government websites or breach highly sensitive information. The anarchic nature of global cyberspace—with no spearheading institution to confront or manage conflicts—provides little incentive to refrain from such attacks, as the threat of being caught and physically retaliated against is muted.

Evolving Cyber Threats against India

South Asia has had its fair share of cyber attacks in recent history: India and Pakistan have been engaged in reciprocal acts of cyber-vandalism, including the defacement of websites and more serious acts like infecting rival airports with ransomware, restricting website owners, and sometimes even locking government systems and data. Acts of information warfare in the vein of cyber-radicalism have also occurred, especially in the context of the Kashmir conflict, where propaganda videos allegedly backed by Pakistan are used to incite violence by appealing to stone-pelters to target security forces. Additionally, non-state actors like militant organizations are increasingly depending upon cyberspace for potential recruitment, with propaganda by the Islamic State managing to attract at least 100 Indians over the past four years.

Recent trends point towards not only an increase in the intensity of such attacks but a qualitative change towards espionage-related attacks that can have more damaging consequences: in 2016, the Indian Army blacklisted a host of spyware applications, including the mobile application SmeshApp that was used for communications purposes by Indian security forces. However, the spyware application was reportedly harnessed by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) to gather information on Indian military personnel. The application could transmit any stored information, including phone calls, text messages, photographs, and even record sounds and geolocation information. In fact, this geotracking of troop movement was allegedly used by handlers based in Pakistan during the militant attack on the Indian Air Force base in Pathankot in January 2016.

The threat to India does not only stem from Pakistan. Reportedly, there also have been suspicions that China has conducted such intel-gathering cyber attacks on India, although officials deny this. In July 2012, over 12,000 email accounts belonging to government officials from the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) and Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), a paramilitary unit deployed along much of 3500 km India-China border, were hacked. A subsequent investigation revealed that hackers were focused on troop deployment and communication between ITBP commanders and MHA officials.

Nightmare Scenarios

The ability to track location through cyberspace also presents potential nightmare scenarios that occur from revealing India’s most vital military assets. Geotracking of the security personnel involved in counterinsurgency operations or manning critical installations like the nuclear, missile, or conventional arms inventory through applications built for espionage, or even applications providing genuine services, can enable militant actors to launch kinetic attacks on such installations. Such geotracking can help hostile actors locate inventory and bases—otherwise secret facilities—while also revealing critical communications logistics. A situation can be imagined where actors engaging in such intrusive tracking may target and subsequently attack a significant portion of their adversary’s nuclear or conventional arsenal, or tamper with military or political lines of communication, thereby disrupting coordination and retaliatory maneuvers. This degrades the deterrence equation, and can potentially lead to a breakdown of deterrence in a worst-case scenario.

Conclusion

If it is to confront the reality that the threat landscape in the cyber domain could jeopardize its most prized military assets, New Delhi will need to begin to prioritize cyber security with the urgency it demands.

With India’s internet usage expected to reach 635.8 million users by 2021, India’s vulnerability to cyber-threats will only increase with present and upcoming electronic and digital infrastructure initiatives. This vulnerability might also extend to critical infrastructure as well as research and military facilities with an increasing range of actors that can develop the capability to exploit such vulnerabilities. Cyberspace demands a state of readiness, and India must build up the capacity to counter nightmare scenarios. For instance, India does not have a dedicated Cyber Security Command in line with the United States or China, although a proposal for a tri-service Defense Cyber Agency comprising almost a thousand personnel does exist. If it is to confront the reality that the threat landscape in the cyber domain could jeopardize its most prized military assets, New Delhi will need to begin to prioritize cyber security with the urgency it demands.

Views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the organizations with which he is affiliated.

***

Image: Pexels via Pixabay