Recently, India’s Ministry of Earth Sciences approved the renaming of its “National Centre for Antarctic and Ocean Research” to the “National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research.” While India has a three-decade history of conducting research in Antarctica, this recent move visibly demonstrates its shifting focus towards the North Pole. Thus far, the impact of climate change on Indian agriculture seems to have been the impetus behind India’s interest in Arctic affairs. There are indications, however, that New Delhi’s engagement with the Arctic will extend beyond the spectrum of scientific research to secure energy resources, and it may also be advantageous to seek a strategic claim over this region.

History of India’s Arctic Activities

In the past several decades, climate change has taken a significant toll on the Arctic, most clearly visible in the trend of diminishing sea ice. The maximum extents of Arctic sea ice cover recorded in 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018 have been the four lowest on record. This phenomenon in the High North is not limited to the Arctic’s littoral countries (Canada, Norway, Russia, Denmark, Iceland, Sweden, Finland, and the United States), but is affecting global sea levels as well as the climate of non-Arctic states. Due to these global effects, non-Arctic European and Asian countries are increasing their presence and participation in Arctic affairs.

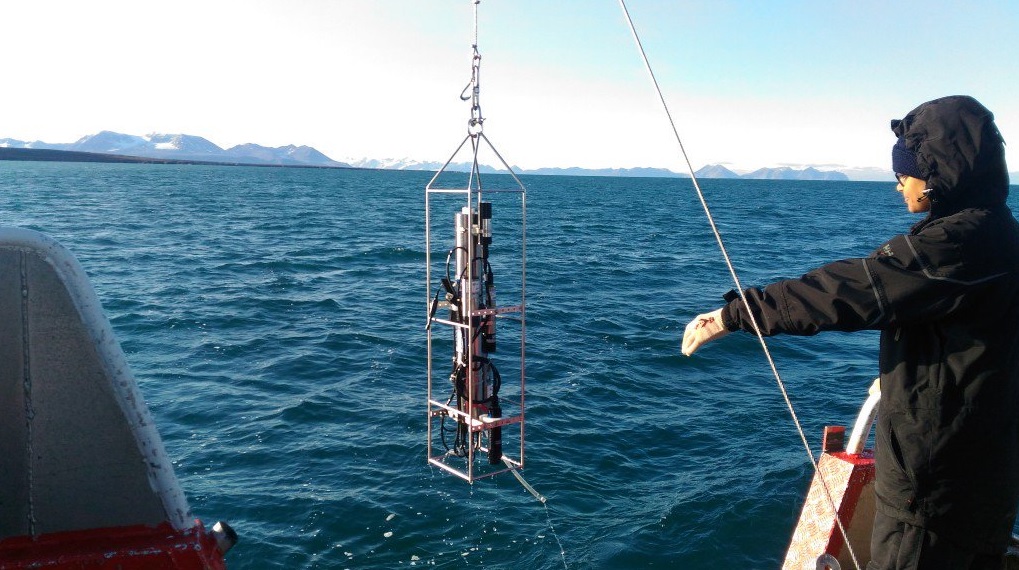

India’s engagement with the Arctic region dates back to 1923, when the British colonial government of India signed the Svalbard Treaty of 1920, which granted Norway sovereignty over the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard. Despite this, India’s focus has mostly been limited to scientific studies at the South Pole, beginning in 1981. However, worries about the impact that a warming Arctic may have on the monsoon—the backbone of India’s agricultural sector, which according to 2016 figures contributes 23 percent to India’s GDP and employs 59 percent of India’s workforce—has recently pushed the country to expand the scope of its polar research beyond Antarctica to focus increasingly on the Arctic. In 2008, India’s first Arctic research station, Himadri, was established on Svalbard. During this time, India has limited itself to scientific research in the Arctic, including glaciological, biological, atmospheric, and marine studies.

India’s Shifting View of the Arctic’s Importance

Until recently, the Indian government had made little effort to expand its focus to include the Arctic’s energy resources. However, in March this year, India received its first liquefied natural gas (LNG) shipment from the Russian Arctic, supplied by independent Russian producer Novatek’s plant at Yamal. Then in June, India received its first LNG shipment as part of the Russian state-backed energy company Gazprom’s twenty-year import deal with the Gas Authority of India, Ltd, also from a plant in Yamal in the Arctic. These shipments signal an important development: that India may be looking to move beyond scientific exploration in the Arctic to leverage the region’s energy resources. This natural gas shipment may be India’s way to meet its renewable energy commitments, made after the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris. But being the third-largest oil importer and consumer in the world, India is perhaps also eyeing hydrocarbons, which are essential to sustain the Indian economy. Apart from a tangible push factor like energy resources, India’s presence in the Arctic also has a normative dimension. As an emerging power, it desires to make its presence felt in all regions of the world and to be a part of agenda setting. Thus, another speculated motivation for India’s move on the Arctic is India’s great power competition with China. The latter’s strategy-laden economic approach in the Arctic seems to have altered the way India perceives the geopolitics of the High North.

On the governance front, India acquired the status of an “observer” in the Arctic Council in 2013 along with China, Japan, South Korea and Singapore. India seems to have sought this status primarily in order to facilitate more research and contribute its scientific expertise to the work of the Council, but likely also to demonstrate itself as a potential great power that has agenda-setting capabilities in that region and throughout the world. As an observer, although it is devoid of any decisionmaking power, India is eligible to participate in meetings of the Council’s Working Groups, which tackle issues ranging from disaster preparedness to biodiversity conservation.

What Can India do Further?

Inarguably, climate change and its potentially-disastrous effects on the monsoon have compelled India to shift its focus to the Arctic. However, there are differing perspectives on India’s view of the Arctic, of which the “global commons theory” and the “exclusivity” debate occupy dominant positions. Some scholars see the Arctic as a global commons, similar to its southern counterpart Antarctica, and argue that India should pursue this idea in its Arctic policy. They reject the “exclusiveness” of the region and claim that New Delhi’s acceptance of observer status in the Arctic Council implies that it has automatically sidelined the global commons idea. On the contrary, other scholars who accept the “exclusiveness” of the region opine that India need not endorse the global commons theory. Instead, they contend that India should diplomatically engage with the eight Arctic countries to push its interests and participate actively in the Council, thereby making its presence felt. By being a part of the Council, India accepts the primary role that the eight states hold in Arctic affairs, but it also has a platform to engage with the littoral countries to further its own interests.

In order to remain relevant in the Arctic game, it would behoove India to begin with releasing a white paper clearly stating its objectives in the region. Additionally, India’s Ministry of External Affairs could set up a desk focusing on Arctic affairs, while facilitating university-level research on the subject. By using its soft power capabilities, India can also collaborate on research efforts with the indigenous communities of the region: for instance, recent initiatives have brought indigenous communities of the Arctic and Himalayas together to brainstorm strategies to combat climate change.

While those outlined above are achievable in the short term, New Delhi can focus on medium-term goals, like establishing another research station apart from Himadri, by collaborating with Canada and Denmark (due to their proximity to the North Pole) or Finland (given the interest of both the countries to take cooperation forward on the scientific front). This idea is very much in tandem with India’s priority for scientific exploration. India could also consider proposing naval exercises with the Arctic states to strengthen relations.

In the long-term, on the geopolitical front, India can plan a counterbalancing strategy to China’s Polar Silk Road by linking the railways and waterways of Russia, Nordic, and Baltic countries with the International North-South Transport Corridor; this would be the quickest and most direct way for India to reach the Arctic and leverage these routes for trade. For this, the INSTC has to stretch beyond the present culminating point, St. Petersburg, and expand northwards and westwards to integrate with the European rail networks such as the North Sea-Baltic Trans-European Transport (TEN-T) Core Network Corridor, the Scandinavian-Mediterranean TEN-T Core Network Corridor, and the Baltic-Adriatic TEN-T Core Network Corridor. However, this will be possible and viable only if India seriously considers trading with the Arctic littoral countries. Therefore, to stay relevant in the emerging great game in the High North, India should take advantage of the observer status it has earned in the Arctic Council and consider investing more in the Arctic.

***

Image 1: NCAOR_Goa via Twitter

Image 2: NCAOR_Goa via Twitter