The 48-member Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) met in Vienna last month to discuss the technical, legal, and political aspects of how non-signatory states to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) might participate in the group. Earlier this year, the June NSG plenary meeting in Seoul concluded without a decision on India’s membership application, despite support for India’s NSG bid by at least 32 countries. However, that meeting set the agenda to hold an extraordinary plenary session “to reach out and see what is possible in the coming months.” The latest round of the Vienna talks focused on India’s entry, as a number of NSG members wanted to bring India on board before the end of the year. Even as India was supported by a majority of the NSG members, China’s continued opposition to India’s application, as well as concerns raised by a few other countries like Austria, Ireland, New Zealand, Brazil, Switzerland, and Turkey, once again left matters undecided.

What Now?

India has two options at this stage. The first approach, as Ambassador Shyam Saran has pointed out, would be to “preserve the substantive gains already obtained through the waiver rather than to push hard for membership.” This strategy may be justified by the fact that India already has the 2008 waiver, which facilitates its access to relevant nuclear technology, materials, and equipment through the several nuclear energy cooperation agreements already entered into. Hence, in practical terms, India’s non-participation in the NSG will not be a debilitating factor for its growing nuclear commerce with other nations. India already has civil nuclear cooperation agreements with several countries like the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, Canada, Australia, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Argentina, Kazakhstan, and now Japan. Additionally, India’s membership experience thus far shows with a fair degree of certainty that China will continue to obfuscate its NSG entry, unless there is a radical change in the power politics of the two nations. Despite its own proliferation history, China may never acknowledge India’s responsible nuclear nonproliferation track record. In fact, China’s strategy is to scuttle India’s NSG bid by raising one issue after another. Given this, India may adopt a cautious approach and forsake membership of the NSG even as it continues to demonstrate its commitment towards strengthening the nonproliferation regime.

The second option for India is to weigh the importance of its NSG admittance. As Ambassador Shyam Saran has argued, given the expansion of the nuclear energy market and associated proliferation risks, the NSG Guidelines might get revised “in a changed geopolitical scenario.” Even with the 2008 NSG waiver, India must pursue efforts to seek NSG entry as a participating government (PG) because, as a PG, India will be involved in the decisionmaking process of the export control group concerning global nuclear commerce. Being a part of the decisionmaking process, India will be privy to the consensus rule and can ensure that no amendments detrimental to its nuclear commerce are made by any PG, some of which are still upset about the 2008 waiver. Further, India’s inclusion into the NSG would legitimize the waiver and would dispel criticism concerning the status of “special exception” given to India. Also, NSG participation would resolve all ambiguity on India’s status of being an outlier state. As I have argued elsewhere, India would acquire the status of a de facto nuclear weapon state and this will bolster India’s position in the nuclear security regime.

Understandably, the benefits of NSG participation would be many and hence it would be wise for India to reinforce efforts towards this end. India is of firm belief that the NSG must follow a merit-based approach to membership, and most of the NSG PGs feel New Delhi has basis for membership on merit. (I reviewed India’s merits for NSG membership back in July, here.) However, China which has been blocking India’s NSG bid, calling for a two-step non-discriminatory approach as a solution to admit non-NPT members into the grouping. Underlying China’s approach lies its two-pronged objective to obfuscate India’s entry into the group and simultaneously push Pakistan’s case for membership. However, there is a sea of difference in the nonproliferation credentials of India and Pakistan. A recent report by Project Alpha, King’s College London outlines in detail the “deceptive methods” carried out by Pakistan to illicitly acquire nuclear materials and technology for enhancing its strategic program, through a complex network of foreign suppliers, particularly China.

Strategy for Successful Entry into NSG

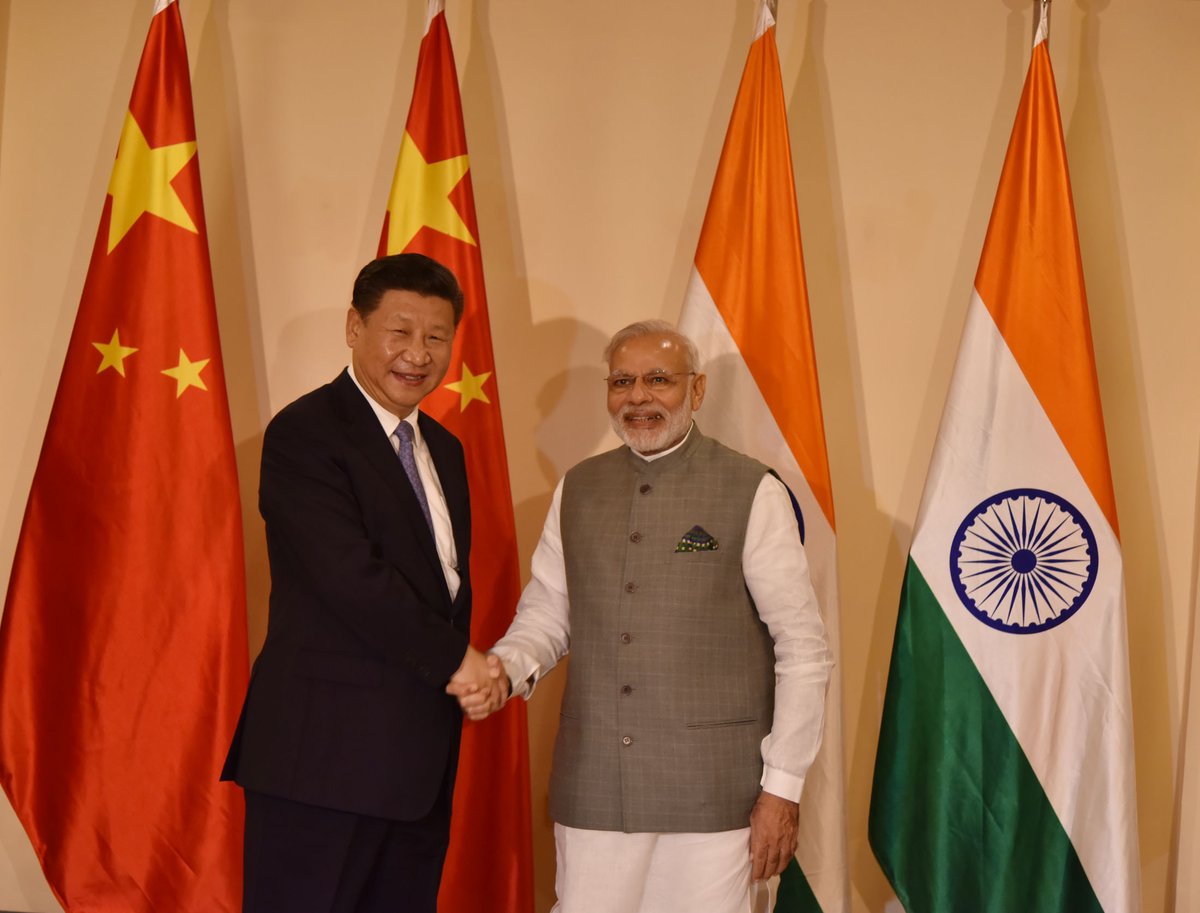

It is quite likely that China may never objectively assess India’s NSG bid solely on the basis of its nonproliferation credentials. It will continue to block India’s candidature for one reason or another. However, India must continue to strive for NSG membership through confident yet quiet diplomacy. With the Trump administration now taking over, India must press for strong support which was evident during the Bush administration. President-elect Donald Trump has endorsed Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s work, and it is believed that the two leaders will share good chemistry. On the few existing naysayers, such as Austria and Ireland, India must make concerted efforts to address their concerns. Winning over the few opposers coupled with strong support from the United States will place India in a better position to counter China’s reticence.

For the 48-member NSG, it remains a litmus test whether the export control group objectively assesses India’s merits to play a major role in matters of nuclear security governance. Alternatively, China may be able to convince the NSG to encourage and reward a nuclear proliferator like Pakistan.

Editor’s note: Despite concerted efforts in 2016, membership of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) still eludes India and Pakistan. This two-part series analyzes India and Pakistan’s next steps to further their NSG candidacy. Read the entire series here.

***

Image 1: Flickr

Image 2: Narendra Modi, Flickr