As the United States continues its withdrawal from Afghanistan, the new administration in Washington is to decide on a roadmap to peace in Afghanistan that offers the United States a winning narrative of achieving its political goals, despite battlefield losses. The stalemate in the intra-Afghan negotiations amidst continued violence has exposed the flaws in the Doha agreement between the United States and the Taliban, which left the key issues of the ceasefire, the fate of Afghanistan’s democratic systems, and protection of minority, women, and civil rights to be decided through intra-Afghan negotiations. With a surge in the efforts of the international community to expedite the Afghan peace process, the role of regional political actors has become imperative to understand in any future negotiation with the Taliban.

Past policy research, however, has primarily focused on the perspectives of the Pakistani state whereas little attention has been paid to the role of other Pakistani political actors in the Afghan peace process.

As Afghanistan’s eastern neighbor, Pakistan has a significant role to play in the country’s future. Past policy research, however, has primarily focused on the perspectives of the Pakistani state whereas little attention has been paid to the role of other Pakistani political actors in the Afghan peace process. This policy memo outlines the role of Pashtun-nationalist and Islamist political parties in fostering peace in Afghanistan. The role of these political parties is important because of their long-term, multilayered ties with political actors in Afghanistan, similar experience of democratic interruption and illiberal politics, and their comparatively higher resilience against non-democratic forces. Willing to support the peace process in Afghanistan with a more realistic understanding of Afghan society, these political parties could be an asset for Pakistan in fulfilling its objective of securing the western border against terrorism and foreign intervention.

The Problem of Democratization in Afghanistan

At the 2001 Bonn Conference, expectations of successfully democratizing Afghanistan were high among international and Afghan policymakers. By the 2019 elections, however, it had become clear that the democratization process in Afghanistan had not unfolded according to expectations, leading one analyst to claim that the country’s democracy might be seeing its “slow death.” In addition to the growing violence and expansion of Taliban controlled-areas, a major impediment to democratic development in Afghanistan has been corruption and poor governance by the elected regime. Additionally, the presidential constitution concentrating authority in the central government in an ethnically and religiously diverse country has contributed to local warlords taking control over regions far from the capital city.

The international community’s response to failing democracy in Afghanistan was primarily an “events-focused affair,” specifically targeting the domestic election process rather than recognizing the long-term transition to democratic norms.1 Additionally, with their explicit involvement in strengthening the government in Kabul, international forces unintentionally substantiated the opposition’s criticism of President Karzai as a “foreign agent” imposed on Afghanistan. As democratization requires a change from within, the international community has now realized that the problem of democratization in Afghanistan needs to be a domestic concern that must proceed further without external intervention.

The majority of Afghanistan’s citizens unquestionably support a democratic political system. The reported 70 percent voter turnout in the 2004 elections, despite the prospect of terrorist attacks on voting booths, demonstrates their acceptance of representative democracy. In 2006, close to 77 percent were satisfied with the democratic efforts in the country and over 65 percent were optimistic about the freedom and fairness of future elections. Despite low turnout in the 2019 elections, over 70 percent of respondents to a 2020 survey on intra-Afghan talks preferred to see a republic system in Afghanistan, compared to seven percent who supported an Islamic Emirate.

The Taliban might also struggle to gain the desired share in power through a democratic system, given their lack of popular support. Hence, the future political system in Afghanistan might be an important point of discord between the Taliban and the government.

Yet, the threat of a theocratic Islamic Emirate still looms large. While the Taliban have not openly rejected democracy, some of their statements indirectly characterize liberal and democratic values as non-Islamic. The Taliban might also struggle to gain the desired share in power through a democratic system, given their lack of popular support. Hence, the future political system in Afghanistan might be an important point of discord between the Taliban and the government. Meanwhile, the democratically elected government in Afghanistan is reliant on U.S. and European actors for financial and moral support, internal dissension among the political parties and leadership is high, and democratic institutions still lack the cohesion and defined mandate present even in the weak neighboring democracies such as Pakistan and Iran.

Why Pakistani Political Parties?

This policy memo outlines the role of Pashtun and Islamist political parties concentrated around the Pakistan-Afghanistan border in advancing democracy in Afghanistan. The selected Pashtun political parties include the Awami National Party (ANP), the Qawmi Watan Party (QWP), and the Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party (PKMAP). Although the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) is not a political party, its role is also analyzed owing to two of its leaders’ presence in Pakistan’s National Assembly and the party’s strong political following in the Newly Merged Districts (NMD).2 The selected Islamist political parties include Jamat-e-Islami (JI), Jamiat Ulema Islam-Fazlur Rehman (JUI-F), and Jamiat Ulema Islam-Samiul Haq (JUI-S). Given the problem of democratization in Afghanistan and the challenges the international community has faced in addressing it, this policy memo presents these political parties as key actors in assisting in democracy and peace-building efforts in the country based on the following three rationales.

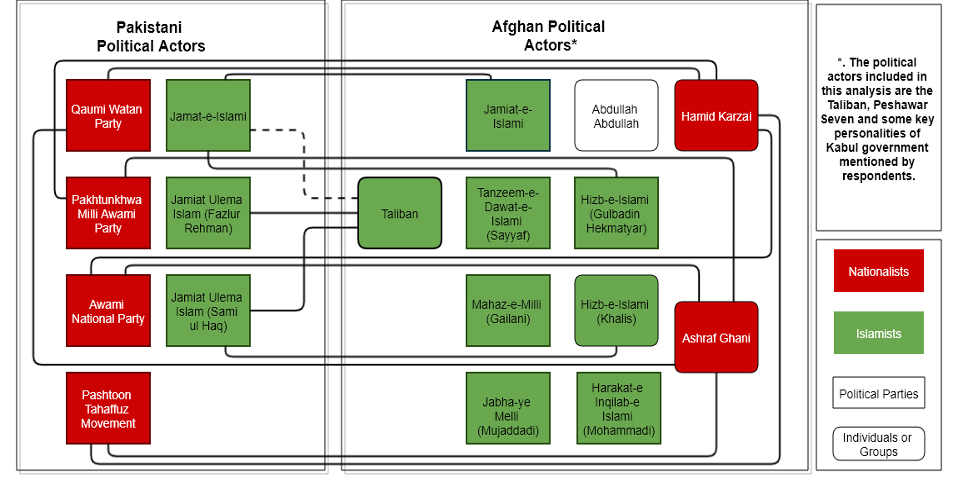

First, Pakistani political parties have deep-rooted multilayered ties with Afghanistan. A preliminary analysis of these relationships based on a review of archival data3 and literature, and interviews with the leadership of the political parties [see Figure 1], show that many Pakistanis view their ties with Afghanistan in light of the arrival of Islam in the region – a connection that proceeds creation of Afghanistan and Pakistan as a sovereign state. Tribal relations superimpose political relations. For instance, Pashtun leadership in Pakistan respects Hamid Karzai not because he was the former President of Afghanistan but because he is a tribal leader. These tribal relations often solidify into family relations through intermarriages. For instance, Afrasiab Khattak, a former member of ANP and current political leader of the PTM, married an Afghan woman while he was in exile in Afghanistan and still has family there. Additionally, some Pakistani politicians, like Mehmood Khan Achakzai the chairman of PKMAP, have had historical economic relations with Afghanistan.

During the Soviet War of 1979, Islamist political parties built a strong presence in Afghanistan, working closely with the Peshawar Seven – Sunni Islamists political parties of Afghanistan having support of Pakistani state. With the rise of the Taliban in the late 1990s, all political parties claim to have built political ties with the Taliban leaders. 4 Yet their relationship with Peshawar Seven varies. JI has closer ties with Jamiat-e-Islami and Hizb-e-Islami (Gulbaddin), and JUI(S) is historically closer to Hizb-e-Islami (Khalis) (though it remained a resistance movement, not a political party). 5 Naturally, these Pakistani political parties have had higher stakes in the political stability of Afghanistan and, unlike the international community, are likely to remain directly involved in efforts to bring peace and stability in Afghanistan.

Second, there are important similarities between Pakistan and Afghanistan’s political systems that allow Pakistani political parties to suggest contextually relevant and realistic goals for democracy in Afghanistan. Both Afghanistan and Pakistan are multiparty democracies, and both have faced several interruptions in their respective democratic transition.6 Political parties in both countries lack experience in internal democratic practices and organizational complexity, and suffer from patronage politics, authoritarian culture, and internal fragmentation.7 The ideological demarcation between ethnic and Islamist parties in Afghanistan, with the former having leftist inclinations, is illustrated in the Pakistani political parties of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) and Balochistan.8

Yet, Pakistani political parties have had a much longer experience with democracy and, consequently, maintain a relatively more organized and secure environment for political activists.9 Even during periods of military dictatorships, Pakistani political parties served both as a platform of resistance against military rule and as a tool to win popular support for military rulers.10 The ethnic and religious political parties of Pakistan, which are the focus of this policy paper, have received limited but stable electoral support and have played a vital role in policymaking through forming coalitions with mainstream parties.11 While their influence declined following the victory of Pakistan Tahreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) in the 2018 federal elections, they did not completely disappear from the country’s political scene.

The ethnic and religious political parties of Pakistan, which are the focus of this policy paper, have received limited but stable electoral support and have played a vital role in policymaking through forming coalitions with mainstream parties.

In contrast, political parties in Afghanistan have had fewer opportunities to organize themselves. They originated under the influence of regional political actors; while the USSR patronized the leftist political parties, Pakistan supported Sunni and Iran supported Shia/Hazara political groups. In the post-Taliban period, factional politics dominated the country, with several splits in Islamist and leftist parties and the emergence of many new liberal democratic parties.12 However, the surge of party politics soon fizzled out as the party law in 2008 imposed stricter rules for new party registration. In addition, the Single Non-Transferrable Vote (SNTV) system in Afghanistan encouraged voting for candidates over political parties.13 Hence, key political leaders in the Kabul government, like Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani, have no affiliation with any political party.

As this political system in Afghanistan will be a key agenda item of any future talks on Afghanistan, Pakistani political parties can share their experiences with their partners in Afghanistan to outline some useful constitutional and political reforms in Afghanistan. However, such an experience-sharing exercise would likely be perceived by the Pakistani establishment as an intervention into state policy, planned with the objective of controlling the alleged Indian-supported terrorism and irredentism in Pak-Afghan border areas.

Pakistani Political Parties and the Future of Afghanistan

In interviews with the political leadership of the aforementioned Pakistani parties, I asked them to predict their role in three possible future scenarios. First, the Taliban agreeing to share power as a political actor with minor changes in the current republic system; second, a stalemate with the Taliban reverting to the use of force for political control while the government continues the current republic system; and third, the onset of a 1990s-like civil war.

Scenario One: Continuation of the Current Republic System with Taliban as a Political Actor

Almost all respondents maintained that this scenario is very unlikely, and the peace process would take time and require major shifts in the current Afghan political system. However, they all agreed to help improve diplomatic ties between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Interestingly, both Islamist and Pashtun leadership endorsed Pakistan’s stance on the designation of the Durand Line as an international border. While Pashtun leaders agreed to play their part in mediating negotiations between the two governments on the Af-Pak border dilemma, Islamist political leaders were confident that the Taliban already respected Pakistan’s territorial sovereignty.14 Political leaders from both strands supported converting the Durand Line to a soft border and removing the border fencing, which was considered as against both national and public interests. Importantly, Pakistani Islamist parties were not too supportive of the continuation of the republic system in Afghanistan and had no intention of helping the Taliban transform into a democratic political party.

Scenario Two: Stalemate in the Peace Process with Continuation of Violence

When asked about the future of the intra-Afghan dialogue, most respondents from both Islamic and Pashtun political parties predicted something closer to scenario two. In a stalemate situation, Pashtun political leadership indicated they would continue providing moral support to the Ghani government by endorsing its stance as the legitimate government in Kabul. The Pashtun parties could serve as a political voice against Taliban-led activities in Pakistan and against the Pakistan government’s use of the Taliban as a proxy. In this regard, the PTM’s role is particularly significant as it has been actively mobilizing against the Pakistan government’s support for the Taliban. In contrast, Islamist political parties believed that the continued ties between the Taliban and the Pakistani government are critical for serving Pakistan’s national interests. The JUI(F), however, seems to have adopted a more balanced approach as its leadership vowed to continue pushing both Afghan government negotiators and the Taliban to restart the dialogue process in case of an interruption or stalemate situation and believed that the Pakistani state should adopt a similar position while not directly interfering in the internal matters of Afghanistan.

Scenario Three: Civil War

Respondents had divided views on this scenario. The majority believed that due to the stakes regional and global forces had in Afghanistan, the spillover effect on Pakistan would shift the focus of Pakistani political parties inward considering the likely influx of refugees and the possible disruption in the security situation in their political strongholds in KPK and Balochistan. Some politicians of PTM and PKMAP leaders held that civil war in Afghanistan might fuel Pashtun secessionist movements. However, most believed that Pakistani Pashtuns would not be interested in supporting a secessionist movement as Pashtuns have urbanized and holds economic interests in non-Pashtun areas such as Karachi.

Recommendations for Pakistani policymakers

Given the role Pakistani political parties can play in improving Pakistan’s relationship with Afghanistan and in helping their Afghan partners reach a peaceful settlement, they could be an asset for Pakistan seeking to raise its profile in regional politics through active role in Afghan peace process. Yet, for building a workable partnership with these political parties, Islamabad must review its Afghanistan policy.

Build a Unified Afghanistan policy

Pakistan should work towards building a unified Afghanistan policy with the involvement of as many domestic stakeholders as possible. Some stakeholders, such as the PTM, might pose a security challenge, while others might be seen as political competitors to the current PTI government. Yet, the government cannot overlook the integral role these parties can play in developing relations with different political actors in Afghanistan and in winning domestic support for the Pakistan government’s Afghan policy.

Pakistan should work towards building a unified Afghanistan policy with the involvement of as many domestic stakeholders as possible.

Recognize the Importance of Pashtun Ties

Pakistan should reorient the current Afghanistan policy that is built on fear of Pashtun irredentism; instead, use Pashtun ties as a binding rather than a dissenting factor. As noted above, Pakistani Pashtuns have limited support for separatist movements, and this fear of Pashtun irredentism is founded on misperceptions.

Engaging with Other Political Actors

Pakistan can broaden and balance its involvement in Afghanistan by building ties with both Afghan nationalists and Islamist elements by sourcing help from Pakistani political parties. Relying only on the Taliban not only limits policy options but also triggers Talibanization in Pakistan

Prioritize an Afghan-led Democratic Transition over Border Fencing

Protect the border from the spillover effect of growing violence and terrorism in Afghanistan by supporting an Afghan-led democratic transition instead of fencing off the border. Recognize that fencing cannot protect against the intangible ideologies of terrorism but can only lead to increased grievances in cross-border communities, fueling anti-state sentiments in local population. As the Afghan government does not approve of this unilateral decision by Pakistan, fencing can be a source of long-term bilateral tension on Pakistan’s western border.

Conclusion

In a world where war is no longer a state-centric affair, the efforts for peace and democracy must broaden to acknowledge the role of non-state actors. Yet, democratic transformation and liberal institutionalization requires persistence, which is hard – if not impossible – to achieve when democracy building and institution building goals are attached as corollaries to more primary strategic and military goals. As the intra-Afghan talks proceed, the U.S.-experience in Afghanistan can provide a lesson in the limitations in U.S. policy of transferring democratic ideals abroad.

Stimson South Asia Program Visiting Fellows represent a diversity of perspectives and experience. As members of a term academic program, their writing and views do not necessarily represent those of the South Asia program or of the Stimson Center.

Editor’s Note: This piece is part of a collection of policy memos published by South Asian Voices Visiting Fellows and was originally published on the Stimson Center website in April 2021. The Visiting Fellowship is a year long fellowship that combines professional development of research, writing, and public speaking skills with extensive exposure to the D.C. policy community. More information on the South Asian Voices Visiting Fellowship is available here.

***

Image 1: WAKIL KOHSAR/AFP via Getty Images

- Noah Coburn and Anna Larson, Derailing Democracy in Afghanistan: Elections in an unstable political landscape (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), 151.

- As the democratic process of open elections has only recently started in NMD, other Pashtun and Islamist political parties discussed in this paper have limited presence in this important region at the Pakistan Afghanistan border.

- Arif Sultan and Mian Muhammad Shafi, Afghanistan Significants: A Monthly Synthesis of Media Reports (Islamabad: Institute of Policy Studies, 1989-1997).

- The dotted line between Jamat-e-Islami and Taliban in Figure 1 is because while the Jama’at leaders I interviewed held that they have ties with Taliban, neutral sources like journalists and analysts held that Jama’at has closer ties with the Rabbani-led Jamiat-e-Islami and Hizb-e-Islami of Hikmatyar and not as much with the Taliban.

- While these political parties have passed through several splits, many of their leaders are part of the current Kabul government.

- Mariam Mufti, Sahar Shafqat, and Niloufer Siddiqui, Eds. Pakistan’s Political Parties: Surviving between dictatorship and democracy (Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2020); National Democratic Institute, Political Parties in Afghanistan: A Review of State and Political Parties after the 2009 and 2010 Election (Washington DC, 2011).

- Ibid.; Thomas Ruttig, Islamists, Leftists – and a Void in the Center: Afghanistan’s Political Parties andwhere they come from (1902-2006) (Kabul: Konrad Adenauer Foundation, 2006).

- Ruttig, Islamist, Leftists – and the Void in the Center, 44.

- This is not to overlook the political struggle of Pashtun political parties, that have faced bans, detention of political leadership, and terrorist attacks on their rallies and public meetings.

- Iqra Mushtaq, Fawad Baig, and Sehrish Mushtaq, “The Role of Political Parties in Political Development of Pakistan” Pakistan Vision 19, no. 1 (2018), 188; Mufti, Shafqat, and Siddiqui, Pakistan’s Political Parties, 2.

- Muhammad Mushtaq, “Ethno-Regional Political Party Success in Pakistan (1970-2013): An Analysis,” ISSRA 10, no. 1 (2018), 97-116; Husnul Amin, “Mainstream Islamism without Fear. The Cases of Jamaat-e-Islami and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam in Pakistan.” Romanian Journal of Political Sciences 14, no. 2 (2014): 126-157.

- Muhammad Mushtaq, “Ethno-Regional Political Party Success in Pakistan (1970-2013): An Analysis,” ISSRA 10, no. 1 (2018), 97-116; Husnul Amin, “Mainstream Islamism without Fear. The Cases of Jamaat-e-Islami and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam in Pakistan.” Romanian Journal of Political Sciences 14, no. 2 (2014): 126-157.

- Under SNTV, parties have to compete with independent candidates in multi-member constituencies and could only win seats if they can effectively manage the division of vote among multiple candidates in one constituency. Andrew Reynolds and Andrew Wilder, Free, Fair or Flawed: Challenges for Legitimate Elections in Afghanistan (Kabul: Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, September 2004), 12, accessed March 23, 2021. https://www.refworld.org/docid/47c3f3c71a.html.

- In another piece, I have outlined several reasons why this might not be true and what factors might refrain Taliban from accepting Durand Line as an international border. “The Future of Pakistan-Taliban Ties in Afghanistan” South Asian Voices, August 5, 2020, accessed March 23, 2021, https://southasianvoices.org/the-future-of-pakistan-taliban-ties-in-afghanistan/