More than two years into their rule, the Taliban persists in systematically eradicating the legal rights, freedoms, and human status of Afghan women and girls. In early April 2023, the Taliban further restricted Afghan rights by forbidding women from working for the United Nations mission in the country. This restrictive policy severely hampers the international community’s ability to address urgent needs and impedes progress toward stability and development in Afghanistan.

The dire situation in Afghanistan has forced female intellectuals, journalists, and activists to flee the country, as the Taliban’s restrictions on women’s freedom of movement, employment, and education have effectively jailed women within their homes. The international community continues to rely on withholding formal diplomatic recognition of the Taliban as a means to influence their policy choices. Two years into the Taliban rule, the escalating discriminatory decrees and bans on women highlight that withholding international recognition alone is insufficient to change the fate of women and strengthen spaces for them to enjoy fundamental rights.

A Steep Decline in Women’s Rights

Despite their assurances to protect women’s rights and enable their education and employment within the bounds of sharia law, the Taliban swiftly initiated a crackdown on the rights of Afghan citizens, with women bearing the brunt of the imposed limitations. The systematic repression of women’s rights has emerged as the predominant and enduring trait of the de facto authority, calling into question the effectiveness of international policy to withhold recognition of the Taliban as leverage.

Prior to the Taliban’s seizure of Kabul, educational institutions in the city followed a co-educational model, where women comprised 70 percent of the teaching staff. Women held approximately half of the positions in the civil servant corps, and 40 percent of the physicians in the city were women. Afghan women enjoyed the legal freedom to decide their attire and move independently in public spaces. With the Taliban’s rise to power, these liberties were replaced with severe penalties and restrictions, including a ban on going to parks, gyms, and public bathing houses, obstructing co-education and education beyond the sixth grade, coupled with severe limitations on employment.

The further restrictions on women’s rights in 2023 demonstrate the ineffectiveness of withholding diplomatic recognition from the Taliban, and so Europe, the United States, and the UN should consider using more targeted approaches that could incentivize the Taliban to change policies toward women.

In December 2021, the Taliban’s leader, Amir Haibatullah Akhundzada, issued a decree that is frequently cited by Taliban representatives as evidence of the Taliban’s commitment to women’s rights. This decree includes provisions related to protecting some women’s rights, such as requiring women’s consent in marriage, prohibiting the exchange of daughters to settle disputes, recognizing women’s rights to mahr (wealth transfer to the bride), and acknowledging their right to property and inheritance based on sharia law. However, the decree does not address women’s rights to education and employment. Since, they have implemented more than 140 orders and decrees introducing additional constraints on girls’ education and female lecturers at universities.

The previous bans on women attending university and working in NGOs, coupled with the April 2023 restriction on employment at the UN, have left the international community further disappointed in the Taliban’s assurances. Even with the exception for health and education NGOs, the ban has had significant ramifications. Prior to the ban, women constituted 30 to 45 percent of the staff in international NGOs and 50 to 55 percent in national NGOs. This restriction has put at risk the delivery of essential humanitarian aid vital for the survival of millions of Afghans.

Following these policies, women took to the streets in peaceful protest. These demonstrations, led by women, began in Herat province in western Afghanistan and swiftly spread to various other provinces by early September. The Taliban’s response was harsh from the outset; cadres disrupted protests, beat protesters, and arrested and tortured journalists who were covering the demonstrations. Taliban enforcement arbitrarily detained notable women’s rights activists Manizha Sediqi, Parisa Azada, Neda Parwani, and Zhulia Parsi; Neda and Zhulia were recently freed.

These actions not only have severe and long-lasting consequences for women and girls but also undermine the social and economic fabric of Afghan society, as half of the population is deprived of the opportunity to contribute to their country’s future.

International Response So Far

The severe crackdown on women’s rights by the Taliban has generated international condemnation. The United Nations, Europe, and the United States have attached conditions to their recognition of the Taliban, including adhering to UN human rights principles, restoring rights to women and girls, and establishing an inclusive government. Though the Taliban has not yet received formal recognition from any country or international body, a few governments, such as China, gave de facto recognition to Taliban’s state control in 2023.

Western nations have taken steps to isolate the new regime, which included reducing development assistance, freezing assets, and imposing sanctions. These measures, combined with the Taliban’s own mismanagement, contributed to a significant downturn of Afghanistan’s economy, with a contraction of 20 percent within a few months.

After over two years in power, none of the warning signs of impending disaster and the consequences of withheld international recognition seem to concern the Taliban leadership enough to draw back their restrictive policies. Thus, the international community, notably the United States, must move beyond mere recognition withholding in the year ahead. Leveraging the UN’s role as a coordinator for the international community’s response to the Taliban, nations should collaboratively implement strategies for accountability, placing additional sanctions on Taliban members and removing the waiver on their travel. The further restrictions on women’s rights in 2023 demonstrate the ineffectiveness of withholding diplomatic recognition from the Taliban, and so Europe, the United States, and the UN should consider using more targeted approaches that could incentivize the Taliban to change policies toward women.

Is Recognition Effective Leverage?

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres emphasizes the significance of recognition as “the sole leverage available” to motivate the Taliban to uphold human rights and embrace a more inclusive form of governance. He advocates for a unified stance among UN member states to exert maximum pressure on the Taliban. Most international governments have used terminology carefully to avoid bestowing formal legitimacy onto the Taliban, employing the terms “de facto government” or “interim government” to refer to the Taliban since they assumed power.

Withholding formal recognition, without other enforcing tools, offers the international community limited leverage. Although limited leverage is better than none at all, the past two years have shown that continuing this policy through 2024 cannot revive the rights of Afghan women.

Historically, the criterion for recognizing a government has been based on “effective control,” which refers to a sufficiently established governing body. It stands to reason that recognition takes time as states evaluate the likelihood of the Taliban’s permanence, particularly since they came to power through extra-legal means. Further, while the Taliban currently has military control over most of Afghanistan, including Kabul, this control has been established for a relatively short period of time. Beyond the monopoly of use of force, the Taliban’s administration is falling short in key areas of governance, from providing education to economic growth.

Generally, regimes that lack recognition as legitimate governments may not have the ability to utilize the domestic courts of other nations, assert ownership over state-owned assets situated abroad, exert control over their country’s foreign diplomatic establishments, or enjoy the benefits of various other privileges that would be accessible to them if they were acknowledged as legitimate entities. To date, the international community’s strategy has been to withhold this privilege to incentivize the Taliban to consider policy reform toward women’s rights.

Withholding formal recognition, without other enforcing tools, offers the international community limited leverage. Although limited leverage is better than none at all, the past two years have shown that continuing this policy through 2024 cannot revive the rights of Afghan women. Even U.S. President Joe Biden has expressed skepticism regarding the potential for the Taliban to alter its conduct due to lack of recognition. Furthermore, regional and Western countries alike have expressed concern about the long-term viability of withholding recognition, considering that numerous states now rely on the Taliban to safeguard their interests in the region.

The Taliban currently enjoy de facto recognition, engaging in economic activities with neighboring countries, participating in international meetings such as China’s Belt and Road forum, hosting European and Chinese diplomats in Kabul, and holding meetings with U.S. officials in Doha. No country has openly committed to ousting the Taliban from power, and the United States has firmly rejected supporting resistance groups against them. Despite this de facto recognition, the Taliban have become more rigid in their stance on women’s rights. This suggests that formal recognition may not significantly alter the Taliban’s position and could even solidify it. Since they already enjoy informal recognition and its benefits, the prospect of withholding full recognition is also unlikely to influence their behavior. Hence, more coercive measures, such as withholding waivers on diplomatic travel, are necessary to address the situation.

What Can Be Done?

The reality is that the Taliban have control of Afghanistan and are able to impose their interpretation of sharia law on Afghan women. The international community is unwilling to resist the Taliban through military means and so far, pockets of resistance inside Afghanistan have failed to spread countrywide and are unlikely to see a resurgence in 2024. Afghan women have continued to bravely engage in nonviolent protest, but without the widespread support of Afghan men, their circumstances are unlikely to change in the coming year.

Looking toward 2024, the United States and other countries still have the ability to engage with and exert influence over the Taliban using other incentives, such as imposing sanctions, providing relief from sanctions, offering foreign aid and technical assistance. Specifically, sanctions waivers that allow the Taliban to travel for international meetings should be removed. The freedom to travel internationally has offered the Taliban the illusion of legitimacy and offered personal benefits to the officials engaged in the travel. More Taliban officials, including mid-level officials, could be sanctioned in ways that prevent them from engaging in regional cross-border transactions.

The United States, Europe, and UN bodies should consider judiciously coordinating the implementation of other pressure tools, including international development assistance, diplomatic engagement, sanctions imposition or relief. The leadership of the Taliban recognizes that in order to sustain Afghanistan’s public services and prevent the collapse of the state, they will need financial and technical support. This assistance will help them in developing administrative capabilities and reinforcing their ability to provide security to Afghans, as well as improving fiscal management, technological capabilities, and their capacity to deliver essential services. Recognizing this need, the international community should consider providing financial and technical assistance to the Taliban administrative bureaucracy in exchange for softened policies on women’s rights.

Also Read: Afghan Women and Gender Invisibility under the Taliban: Local Voices and Expectations.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

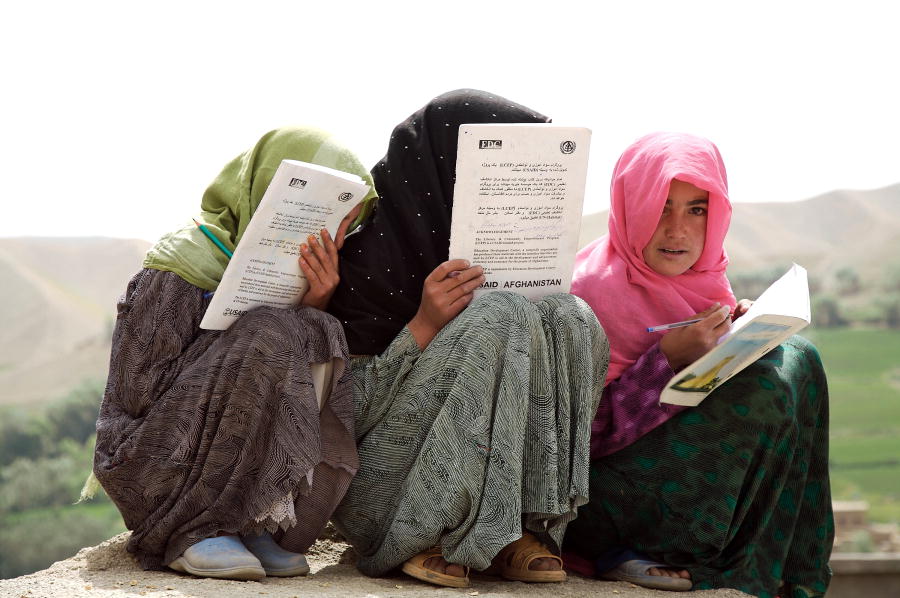

Image 1: Afghan girls studying for exams via Flickr.

Image 2: Women in Bagram, Afghanistan via Flickr.