Democracy in South Asia, as attested by the recently concluded elections in Bangladesh, is taking a frighteningly dark turn. The region is emerging as a zone where powerful regimes crush political opposition and suppress civil liberties. As India and Pakistan also venture into the election jamboree, 2024 serves as an opportune moment to assess the fraying status of democracy in the three South Asian nations and its broader cross-border implications for regional prosperity.

India: A case of democratic backsliding

India’s liberal democracy is under duress as a powerful executive weakens the judiciary and other independent institutions. India’s past experiences show that independent institutions have seldom withstood an onslaught from a powerful executive, most notably seen when the Indian Supreme Court suspended fundamental rights during the Emergency from 1975 to 1977. While the Indian judiciary and the media have complied with Bharatiya Janata Party state directives, it would be a misdiagnosis to estimate that Indian institutions have capsized merely out of a fear of reprisal. The reality is that a large section of Indian elites at the helm of managing institutions are supporters of the BJP’s ideological regime that has a vision for India radically at odds with its founding ideals.

As per a recent survey, more Indians prefer a leader with a strong hand over a democratic form of government.

Paradoxically, the BJP’s authoritarian slide enjoys immense popular legitimacy. As per a recent survey, more Indians prefer a leader with a strong hand over a democratic form of government. Unsurprisingly, the party has faced little pushback for strong-arming its critics. Unlike the West where the educated middle class solidly backs left-liberal parties, in India, the demography serves as a core pillar for the right-wing BJP and has thrown its weight behind the party’s ideological project. Moreover, the BJP, traditionally perceived as an upper-caste North Indian party, has increased its social base to include marginalized caste groups like Other Backward Classes (OBCs), Dalits, and tribals, and also expanded its regional footprint to turn itself into an organizational behemoth.

While the lackluster opposition has not managed to challenge the BJP’s agenda, concerted mass mobilization has pushed back against several right-wing policies on issues such as land and farm reforms and the Citizenship (Amendment) Act in 2019. The BJP can steamroll through the parliament, but social contestation remains vivacious in local settings. But solely relying on India’s constitutional checks and balances to safeguard democracy is naive. While the upcoming general election is widely believed to be a foregone conclusion and will lead to greater power consolidation, social groups operating outside traditional political channels will act as a bulwark if their interests are threatened.

Pakistan: Military supremacy reigns

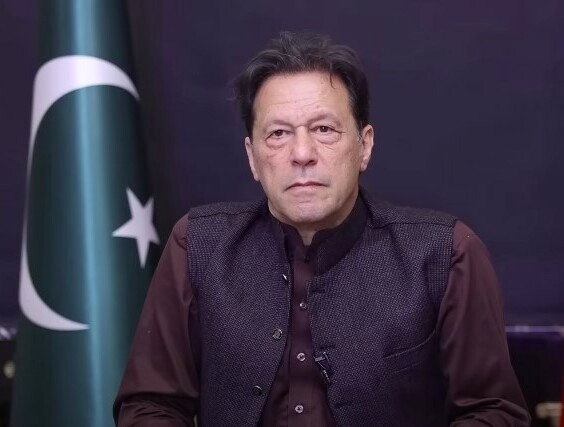

Pakistan’s elections are scheduled for February 8 and seem to follow a familiar pattern in the country’s political history. No civilian leader or party can retain power in Pakistan without the army’s tacit blessings, as seen in the case of ex-Prime Minister Imran Khan. Despite falling out of Rawalpindi’s favor and having a poor governance record, Khan remains the most popular politician in Pakistan, much to the dismay of the army. In his ouster from power, he joined politicians like Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif, who were patronized by the generals and subsequently discarded when they fell out with the army. The military’s aim in 2024 is evidently to ensure that Khan enjoys no second innings as the prime minister and his party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), is decimated until a bunch of yes-men remain.

The army’s embrace of civilian leadership is almost always tactical rather than the result of any genuine commitment to democratic norms. The army is now adverse to being perceived as openly taking power into its own hands and prefers operating from backstage to engineer favorable electoral outcomes, continuing to play one political faction against the other. At the same time, Pakistan’s political class lacks institutional unity and a vision to usher in social transformation.

Considering the entrenched position of the army in Pakistani politics, the election is unlikely to lead to any meaningful deepening of democratization. The election appears like a stratagem by the army to reinstate Nawaz Sharif as prime minister and provide his return a gloss of popular consent. In such a dire strait, Pakistan’s flawed democracy will facilitate little more than a revolving chair of power and patronage.

Bangladesh: One nation one party

Bangladesh has incrementally turned into a de facto one-party state with a growing personality cult surrounding Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. The cult, to a large degree, remains planted in history: endlessly milking the outsized legacy of her father and Bangladesh’s first prime minister, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in securing Bangladesh’s independence. Her critics at home and abroad now paint her as a figure who runs her writ over police, media, and the judiciary.

To her credit, unlike Pakistan, her government has enjoyed a degree of performance legitimacy over the past years due to Bangladesh’s economic growth. This goodwill is, however, fast dwindling. The growth miracle story has lost its mojo as the country remains overdependent on the garment sector and fails to diversify its exports. Soaring inflation and declining foreign reserves have added to public weariness against her rule. Unsurprisingly, Bangladesh’s faltering economic stars have coincided with an increase in government repression. Just in the last few months, thousands of Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) members and activists have been jailed while demanding that Hasina step down and hand over the reins to a caretaker government.

BNP’s boycott of the January 7polls all but guaranteed a fourth-straight term for Hasina, amid poor voter turnout. The opposition continues to take to the streets, questioning the legitimacy of her rule. As she dodges international criticism for not ensuring a free and fair election, Hasina’s more immediate and pressing challenge is the relentless domestic turmoil her regime has to contend with as she begins a fourth-consecutive term.

Conclusion: Regional Implications

There are larger implications of the declining state of democracy in South Asia. First, the tapestry of South Asia is weaved with a single fabric; an increase in repression and violence in one country, especially if it is targeted against minorities, will have a spillover effect elsewhere. In one example of many, anti-Hindu violence in Bangladesh led to retaliatory violence in Tripura against the Muslim community in 2021. Forces of ethno-nationalism and religious fundamentalism in one country provide succor to their counterparts across borders and rally further polarization.

The tapestry of South Asia is weaved with a single fabric; an increase in repression and violence in one country, especially if it is targeted against minorities, will have a spillover effect elsewhere.

Second, rising authoritarianism will not be conducive to South Asian regionalism. Scholarly literature has argued that democracies are less prone to initiating aggression against countries and more likely to foster inter-state cooperation, thereby increasing the scope for shared prosperity. Democracy also aids in creating a more rule-based order for regional governance.

Third, contrary to East Asian nations like South Korea and Taiwan, which grew richer before transitioning to democracy in the late 1980s, authoritarianism is unlikely to drive prolonged economic growth in South Asia. Historical evidence on the relationship between democracy and economic growth in South Asia has indicated that “democracy has a positive and statistically significant effect on economic growth in the region.” As one of the least integrated regions of the world, South Asia will continue to miss trade opportunities for mutual benefit if the turn towards authoritarianism continues. An increasingly repressive state in Pakistan and Bangladesh will find it challenging to monopolize violence, much less foster conditions for significant economic growth.

In many ways, South Asia serves as a microcosm of the poor health of democracies worldwide. As per IDEA’s Global State of Democracy 2023 report, half the countries have witnessed deterioration in at least one indicator of democracy over the past five years. Meanwhile, 2024 has been billed as the biggest election year in history with more than 60 nations going to polls. The developments in South Asia, comprising about a fourth of the world’s population, will cast its shadow on the future course of democracy. As close to a billion voters prepare to participate in the elections, the events this year may well decide whether South Asia’s experiment with democracy receives a new lease of life or enters an era of terminal decline.

Also Read: 2023: Year in Review

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: Attari-Wagah India-Pakistan Border via Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: Imran Khan via Wikimedia Commons