India’s formal invitation to Australia to join the Malabar Exercise 2020 in November has raised two important questions. First, does this signal a change in India’s strategic posturing in the Indo-Pacific? In other words, is India shedding its hedging strategy to tilt more visibly towards the Quad? Second, what future does the Quad hold in the Indo-Pacific?

The Malabar exercises are intertwined with the history of the construct of the Indo-Pacific and the Quad grouping (the United States, India, Japan and Australia). Started in 1992 between India and the United States, the Malabar exercises were dropped in the wake of the India’s nuclear tests from 1997- 2001, before making them an annual event from 2002 onward. The first Quadrilateral meet on the sidelines of the ASEAN Regional Forum in Manilla 2007 dovetailed with the Malabar exercises in Bay of Bengal later that year in September. The exercise saw the addition of Japan, Australia, and Singapore. However, although the exercises were trilateralized in 2015 with Japan, 2007 was Australia’s only appearance. The primary reason for this breakaway was China’s encirclement fears.

China’s objections to the Quad had a considerable impact on India and Australia. New Delhi and Canberra had different reasons for not wanting to offend China. For India, China stands as a strategically superior northern neighbor with which it is tied in an ongoing border dispute and a maritime security dilemma. India thereafter acquired a policy of hedging in the Indo-Pacific somewhere between balancing and bandwagoning (aligning with a threatening country out of security concerns) China. For Australia, China is a significant economic partner and it also had incentives not to go against Beijing’s interests. As a result, the relevance of the Quad faded.

In the last decade, as the region has continued to see a heavy Chinese maritime presence the Indo-Pacific as a strategic construct has gained currency. Simultaneously, the Quad’s perceived role has overlapped with the conceptualization of the Indo-Pacific as a strategic landscape. Therefore, although India and Australia’s strategic concerns regarding their bilateral relationship with China remain, the context and opportunities for regional actors in the Indo-Pacific are continually evolving. The 2020 Malabar Exercise is product of these continuities and changes.

Although India and Australia’s strategic concerns regarding their bilateral relationship with China remain, the context and opportunities for regional actors in the Indo-Pacific are continually evolving. The 2020 Malabar Exercise is product of these continuities and changes.

Is India’s shedding its Hedging Strategy?

From New Delhi’s standpoint, there are three main reasons for inviting Australia to the Malabar Exercise.

First, the invitation is an expected outcome of the growing strategic convergence between New Delhi and Canberra. Since 2015, the two have regularly teamed up for the bilateral naval exercise AUSINDEX (Australia – India Exercise). In 2017, the countries initiated a 2+2 dialogue reviewing their strategic and defense ties. This year in June, the 2+2 dialogue was upgraded from secretary to ministerial level.

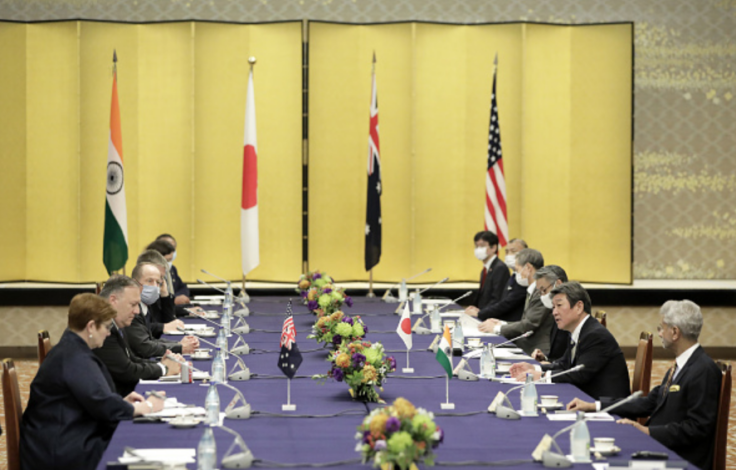

Second, Australia’s participation is the result of the renewed engagements of the Quad 2.0. Since its revival in 2017, the Quad has discussed their visions of the Indo-Pacific and a rules-based order in the region. Despite differences within, the notion of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific has connected Quad members. Alongside the several diplomatic exchanges, the most prominent marker of the Quad’s revival remains the Quad Ministerial Meet in 2020. Australia’s addition to the Malabar exercise was a natural next step under this revival.

Finally, India’s rivalry with China has a significant role to play in this context. The move to invite Australia from this perspective is a logistical step for turning to the Quad for strategic preparedness. India and China are currently engaged in the most charged border standoff in decades, with clashes in June resulting in the first deaths on the Sino-Indian border since 1975. Given China’s already aggressive presence in the Indo-Pacific, this flashpoint is a realization that India needs to be strategically prepared for Chinese aggression in the maritime domain. However, even with the Quad’s shift towards militarization, India has still maintained the room to hedge as it strengthens its strategic relationships with the Quad states without explicitly stating that the aim is to counter China.

Whither the Quad?

There is no doubt that the Malabar exercise upgrades the Quad’s position, however, the Quad still has notable challenges for becoming a strategic platform in the future.

First, there are still considerable differences among Quad member states—historically the Quad has been more symbolism than substance. Questions such as what the rules-based order consists of, how to resolve contested interpretations of the Indo-Pacific, and what the Quad stands for in the region are far from uniformly settled.

Second, the Quad has to provide more opportunities for its states to consistently rely on it to balance China. For that, the Quad needs to be internally stronger on two parameters: strategically and economically. In a situation where China can continue to use its strategic and economic strength to wield its influence in the region, the Quad has to become the viable alternative to balance Beijing. In the absence of that, this military reunion will become another aberration like 2007.

In a situation where China can continue to use its strategic and economic strength to wield its influence in the region, the Quad has to become the viable alternative to balance Beijing. In the absence of that, this military reunion will become another aberration like 2007.

Looking Ahead

While India’s strategic posture is changing in the Indo-Pacific, it is unlikely that it will abandon hedging. India still avoids aiming directly at China, upholds the conciliatory approach to the Indo-Pacific, has decoupled the Quad and Indo-Pacific, and stays away from alliances.

For the Quad, its direction depends on what the member states make of it. If the member states invest considerably the Quad, it could become an agency to shape the Indo-Pacific. Or else it will remain weak at worst, symbolic at best.

***

Image 1: U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Dylan McCord via Flickr