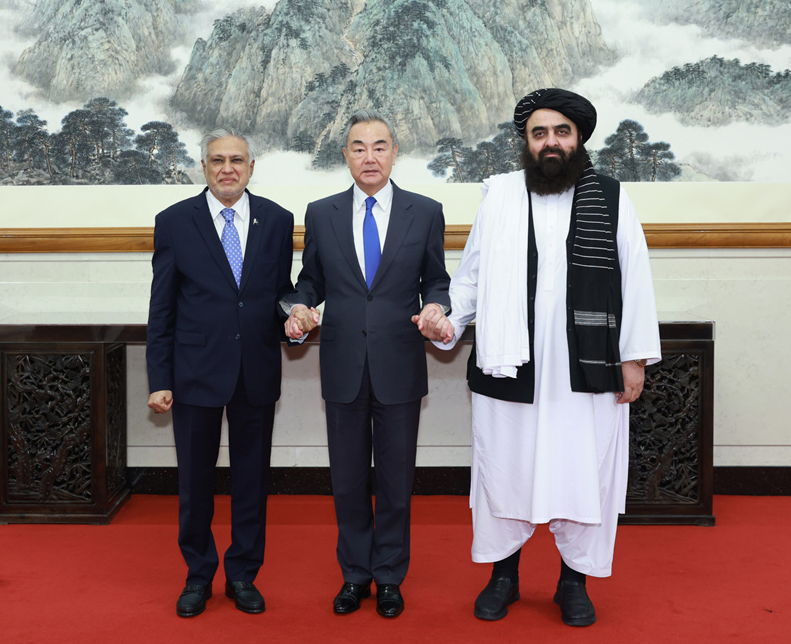

In May, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and China met for a momentous trilateral dialogue in Beijing, which served to restore Pakistan-Afghanistan ties and renewed the grouping’s commitment to extending the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor to Afghanistan. In recent months, China and Pakistan have reiterated their intention to make good on those promises. South Asian Voices spoke with Kamran Yousaf on July 28 about the drivers for and the potentially lasting impact of this forum, prospects for deeper cooperation among the three countries, and how the trilateral could reshape regional geopolitics. Kamran Yousaf is a Pakistani journalist with over two decades of experience reporting on foreign affairs—he currently hosts #TheReview on Express News and has extensively covered the Pakistan-Afghanistan-China triangle for The Express Tribune.

The trilateral meeting between the foreign ministers of China, Pakistan and Afghanistan in Beijing on May 21 received a lot of attention in Washington and other capitals. What do you think the objectives of each side were in engaging through this forum?

KY: All three countries had different objectives for this meeting. But I think this particular initiative was taken at the behest of China, because China is certainly concerned that the situation inside Afghanistan is still very volatile. I’ve spoken to many Chinese officials, and they believe many groups that China feel are a threat to their national security are still operating there. But, unlike Pakistan, they have a more pragmatic approach; instead of going public or using coercive measures, they are following a strategy to convince the Afghan Taliban that if they cooperate with regional countries and with China, then they will have plenty of opportunities for regional integration, trade, economic investment, etc.

When Pakistan and Afghanistan have a troubled relationship, that upsets China, because it can jeopardize China’s own interests in the region, like its objective to extend the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to Afghanistan. So, China feels that if it can bring the two countries together and somehow ease tensions, that can increase its influence in the region and serve its Afghanistan objectives well, because, as I said, China still has considerable concerns regarding the presence of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) inside the country.

For Pakistan, after the Taliban took over, initially there was a lot of enthusiasm that it could really help improve security along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border and address the longstanding problem of militant groups operating from Afghanistan. But those expectations were short-lived as the Taliban aligned themselves with the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and the Hafiz Gul Bahadur (HGB) group. They refused to take action against these groups.

And Pakistan then took certain measures, including imposing restrictions on trade, sending back Afghan refugees, and publicly ridiculing the Afghan Taliban in the hope that the Taliban would mend their ways. But I think that policy did not work, and eventually, Pakistan felt that they had to re-engage with the Afghan Taliban. By bringing Beijing into it, they probably feel that China today has more leverage over the Afghan Taliban than Pakistan and can procure some kind of deal between the two that the Afghan Taliban would genuinely implement.

And finally, when it comes to Afghanistan, it’s now been four years since the Taliban took over, and they’re still seeking international legitimacy. Recently, we saw that Russia formally recognized them, but the Taliban are still waiting on others to do the same. So, they probably felt they could gain more legitimacy through this trilateral framework. In this way, all three countries see some benefit in this relationship.

Pakistan felt that they had to re-engage with the Afghan Taliban. By bringing Beijing into it, they probably feel that China today has more leverage over the Afghan Taliban than Pakistan and can procure some kind of deal between the two that the Afghan Taliban would genuinely implement.

Security challenges seem to have held back Pakistan-Afghanistan relations in recent years. Does the warming of ties between the two signal a serious crackdown by the Taliban on the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)?

KY: I think Pakistan clearly linked the improvement in the relationship with the Afghan Taliban’s action against the TTP and other groups that are attacking Pakistani security forces. I’ve also reported that during a recent engagement that Pakistan had with the Afghan Taliban, they saw a shift in the Afghan Taliban’s approach towards these groups.

For example, we saw that not only were the Pakistani Taliban attacking Pakistani security forces, but Afghan nationals were increasingly joining these anti-Pakistan groups. Based on interactions that I have had with Pakistani officials, the Afghan Taliban really cracked down on those who were facilitating Afghan nationals to join the TTP. Then, there were also reports that some of the TTP fighters were being relocated away from the Pakistan-Afghanistan border areas. On that count as well, Pakistan felt that there was progress.

Pakistan also acknowledged that there are areas where the Afghan Taliban are probably helpless in dealing with these situations. And Pakistani officials understand that. But overall, I think Pakistan feels that, unlike the past, this time the Afghan Taliban seems serious. That is why when Pakistan decided to upgrade the diplomatic relationship with the Afghan Taliban, that was, you could say, an acknowledgement of the efforts that the Afghan Taliban are putting in.

But I do think the situation is very complex. Pakistan would want the complete elimination of what it calls safe havens of the TTP in Afghanistan. And for this, I think Pakistan is now following the template of China—let’s give diplomacy a chance. Let’s engage with the Afghan Taliban more in the hope that they would realize that if they side with Pakistan instead of with the TTP and other groups, they will benefit. China may invest more and CPEC may be extended to Kabul.

To follow up on that, how much, if at all, was the Indian engagement with the Taliban regime in recent months (including a meeting with the Indian foreign secretary in January and a call with the Indian external affairs minister in May) a factor in the warming of relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan?

KY: I think this was one of the factors, but not the only factor. The timing was very interesting. Before the India-Pakistan crisis in May, you didn’t have that immediate threat emanating from the eastern front in India from Pakistan’s perspective. But after the Pahalgam attack, the situation escalated to a point where an all-out war was a real possibility. When it comes to India, New Delhi believes that they need to avoid a two-front situation like facing Pakistan and China at the same time. I think this is also true in Pakistan’s case, and I think it is very possible that Pakistani authorities realized that you cannot have a two-front situation where they have volatile borders both on the eastern front with India and the western front with Afghanistan. That element likely played a role because India seemed to be trying to exploit that rift between Pakistan and the Afghan Taliban. Not only with the high-level engagement but also after the Pahalgam attack, the Afghan Taliban clearly condemned the attack, which was a very positive development from the Indian perspective. So, Pakistan was aware that if relations with the Afghan Taliban remained tense, India could probably take advantage of that.

I think this trilateral meeting was also important because China sent a clear message, not just to Pakistan or Afghanistan, but also to India. They were, in a way, conveying to the Afghan Taliban that your future is with us, not with India. If you cooperate with us, that will give you more benefits. So, certainly, I would not discount the India factor in the recent rapprochement between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

As you noted, one of the major outcomes of the trilateral was a renewed commitment to economic investment in Afghanistan, including the extension of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). However, Chinese economic initiatives in Afghanistan have struggled of late, as evidenced by the recent cancellation of the flagship Amu Darya oilfield collaboration. Why have such projects struggled to take off, and what can both sides do to accelerate the economic relationship and make good on the CPEC extension promise?

KY: The major stumbling block is that there are still many security risks in Afghanistan. And there is a lot of uncertainty around legal guarantees under the Taliban regime, which is also playing a role. I think the recent cancellation of the deal that you talked about primarily has to do with disagreements on transparency and revenue sharing. But overall, there are trust issues between China and the Afghan Taliban. China certainly wants to invest in many areas, but they are probably adopting a more cautious approach.

With the recent trip of Chief of Army Staff Field Marshal Asim Munir to China and Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif set to visit as well, the China-Pakistan relationship appears to be on a strong upward trajectory after some rocking of the boat in the past two years. What are the biggest opportunities in the relationship, and what roadblocks might hold the two governments back?

KY: I think the biggest roadblock is the security of Chinese nationals in Pakistan and their assets. Because over the last two to three years, we’ve seen that despite Pakistan’s promises, Chinese nationals repeatedly came under attack in the country. And that really upset Beijing. I was recently in China, and this was one of the major issues they still flagged. They say they cannot afford their nationals being killed with impunity in Pakistan.

But, I’ve also seen a change on this count recently. I interacted with the Chinese minister of the CCP Central Committee’s International Department, who looks after CPEC. He was in Pakistan last year, and for the first time, he publicly drew a line saying that if Pakistan does not improve the security of Chinese nationals, it will become increasingly difficult for China to make further investments. And that was an unprecedented statement coming from a Chinese minister, because they never publicly criticize their allies.

But between that statement and my trip, both sides really tried to sort out these issues. There was talk of a joint security company, and I believe that there was some kind of understanding reached. The same minister who spoke about linking future investment with the security of Chinese nationals, this time told me that things have really improved and we want Pakistani security forces to ensure better security of Chinese nationals. But the more important thing he said was that we are not afraid of these security challenges. Meaning that despite these security challenges, we are not abandoning Pakistan.

The other factors include the contractual obligations that Pakistan needs to fulfill in the energy sector. We saw that Pakistan had to repay a lot of dues to Chinese companies in the past; that was a major hurdle in the relationship. But overall, I feel after the India-Pakistan conflict, there was positive momentum in the relationship. And if you see the statement from the recent visit of the Pakistani army chief to China, they talk about further deepening their cooperation in defense, and also dealing with hybrid warfare and transnational threats, which is probably referring to the TTP, the trouble in Balochistan, and the threat being faced by Chinese nationals in Pakistan. So, it appears that both countries are cooperating closely to deal with this threat.

You have previously reported that Pakistan and China are considering launching a new regional organization. What do you believe the objectives and membership of such an organization would be? What do you think of reports that the organization would attempt to sidestep SAARC, and are there any comparisons to India’s recent efforts to center BIMSTEC?

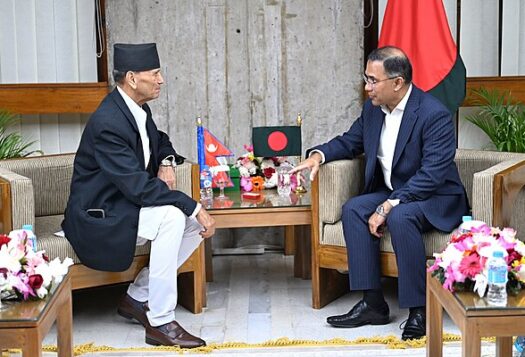

KY: I think this is very significant. On June 19, a trilateral meeting took place between the top diplomats of Pakistan, China, and Bangladesh in Kunming. This was the first trilateral meeting ever between these three countries. And I think this warming of ties between Pakistan and Bangladesh, and then China, stems from the ouster of Sheikh Hasina’s government, following the student protests.

When the Awami League was in power for almost 15 years, relations with Pakistan were really at their lowest ebb. But after Sheikh Hasina’s ouster, things really began to improve between the two countries, and China also started making inroads.

I reported on this trilateral meeting and the idea of creating a new regional organization that can replicate or replace the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation. The Pakistani officials that I’ve spoken to on background acknowledge that such an effort is underway.

They say that such an organization is needed because SAARC has been defunct for around 10 years, due to the tensions between India and Pakistan. India boycotted the summit that was supposed to take place in Pakistan in November 2016 and, since then, no SAARC summits have taken place. So, Pakistan feels that they probably need an organization led by China to fill the vacuum. They also feel that not just Pakistan has had a difficult relationship with India, but other smaller countries in South Asia also have their troubles with India.

They feel that now, given the way China is rising, those countries may have a better alternative, and they can withstand Indian pressure. The whole idea is to eventually create an organization that can replace SAARC and achieve the objectives SAARC failed to, through an entity led by China, which can deliver.

[Pakistan] want[s] China for investment, infrastructure, protecting their larger geostrategic interests, but for economic stability, for sustained IMF support and other financial bailouts from Western-led financial institutions, they certainly need the support of the United States.

We are also seeing changes afoot in the U.S-Pakistan relationship, driven by recent high-level engagements like the foreign ministers’ meeting in July and Munir’s visit to Washington in June. Is this a “reset” in U.S.-Pakistan relations and is it part of Pakistan’s geoeconomic pivot? What are Pakistan’s objectives vis-a-vis the United States?

KY: I think Pakistan’s public position is very clear. And I think even privately, they say the same thing. Ideally, Pakistan wants to have good relations with all big powers, particularly with the United States and with China. And they do not want to be seen joining either of them. China is Pakistan’s strategic partner, and over the last few years it invested billions of dollars in infrastructure projects. It also is a major arms supplier to Pakistan; we now buy more than 80 percent of our weapons from China. We also rely heavily on China when it comes to protecting our interests at global fora, like the UN Security Council. Yet there is a sense within both Islamabad and Rawalpindi that the United States still controls the global financial system, whether the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. For that, Pakistan certainly needs the United States to be on its side, or at least they do not want a situation where the United States creates problems for them. So, they want China for investment, infrastructure, protecting their larger geostrategic interests, but for economic stability, for sustained IMF support and other financial bailouts from Western-led financial institutions, they certainly need the support of the United States.

I’ve spoken to many Chinese officials, and they say that we never objected to Pakistan having good relations with the United States. The only question is whether the United States will have the same approach; will they also say, fine, you can have good relations with China, we don’t object. That is, I think, the major worry. In Pakistan, there are also a lot of skeptics who feel that when President Trump hosted Field Marshal Asim Munir or Minister Dar was invited to the State Department, that there are no free lunches, there must be some hidden agenda behind all these moves, whether that agenda is to change Pakistan’s stance towards Israel or has to do with rare earth minerals.

I believe this rare earth minerals factor is major, because, at the moment, the United States wants to diversify its supply chain since China currently processes 90 percent of such minerals. Pakistan has rare earth minerals in Balochistan and the former tribal areas. After the meeting with Dar, Marco Rubio spoke specifically about cooperation on rare earth minerals. So, Pakistan certainly feels that this recent engagement with the United States shows that it is still a player to be reckoned with.

Views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the positions of South Asian Voices, the Stimson Center, or our supporters.

Also Read: Trilaterals in Testing Times? The Pakistan-Afghanistan Dynamic and China’s Diplomatic Calculus

***

Image 1: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China

Image 2: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China