Pakistan has repeatedly flagged its longstanding concern in Afghanistan – a larger Indian role – to all relevant external stakeholders, most importantly the United States. Pakistan projects this concern as a defensive security interest by accusing India of opening a second front, claiming that India’s intelligence agency, Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), is acting in collusion with militant outfits, specifically the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and Baloch insurgent groups. Pakistan also alleges collusion between RAW and the National Directorate of Security (NDS) of Afghanistan to encourage militancy in Pakistan. This is complemented by their assertion that there are no safe havens for the Afghan Taliban inside Pakistan. Assuming that all of Pakistan’s concerns are taken care of, what would its modus operandi in Afghanistan be and what course of action would it take? How would Pakistan view a militancy-free Afghanistan with a governance system that is imperfect but stable and in control of its territory? Using the logic of backward induction, one can conclude that the United States has no compelling mechanism or leverage that can influence the most important state element within Pakistan, the military. As such, Pakistan’s cost-benefit calculation regarding Afghanistan will stay the same because a politically-divided Afghanistan that is not in control of its territory serves Pakistan’s strategic interests.

The View from Islamabad

All modern Afghan governments, including the one in power at the moment, have refused to recognize the Durand Line, which divides the Pashtun tribal belt between Afghanistan and Pakistan under the 1893 Durand Agreement. However, a stable government in an Afghanistan with no significant internal challenge to its sovereignty or writ could seriously contend the Durand Line issue with Pakistan. Without the insurgency threat, and bolstered with assets capable of delivering firepower from the air, the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) would be a battle-hardened force to be reckoned with. More importantly, a unified Afghanistan would act on the Durand Line issue with internal cohesion. Notably, even the Taliban had refused to confer recognition on the Durand Line during its stint in power in Afghanistan and in fact, instigated Pashtun nationalism on both sides of the line. Pakistan would not want a professional military force presenting a credible challenge on the Durand Line, because it effectively allows Afghanistan to supplement an existing political claim with military capability.

Stable Afghanistan: A Better Market for India

An Afghanistan with a stable regime in power, and without violent terrorism, would provide South Asian countries access to the Central Asian markets, most notably India. Although alternative routes do exist, Afghanistan would inevitably integrate into the network by providing access to Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan among other nations via the Chabhahar Port. That Afghanistan is mainly an exporter of agricultural and primary products and rich in a variety of rare earth minerals implies that it could be a good complement to the growing Indian economy with high domestic consumption. Wedded to this is the fact that most civilians in Afghanistan generally take a good view of India due to historical ties, its $3 billion in development assistance since 2001, and cultural influence due to Bollywood. Additionally, Afghanistan has sought to move away from its trade dependence on Pakistan due to bilateral tensions over the last two years. Due to these reasons, India may be a more attractive option for Afghanistan to trade with instead of Pakistan.

Dependency

A conflict in Afghanistan gives Pakistan an issue over which to bargain with the United States, by virtue of Islamabad providing the most easily accessible and cost-effective route to supply U.S. troops in Afghanistan. The Northern Distribution Network (NDN), a series of commercially-based logistical arrangements connecting Baltic and Caspian Sea ports with Afghanistan via Russia, Central Asia, and the Caucasus cost about $14000 per container compared to $7000 through Pakistan. More importantly, should the United States feel the need to bolster its troop strength, it will need access to those routes. The issue of vertical proliferation and safety concerns related to Pakistan’s nuclear weapons is another factor compelling the United States to remain engaged with Pakistan on constructive rather than confrontational terms.

The Stick

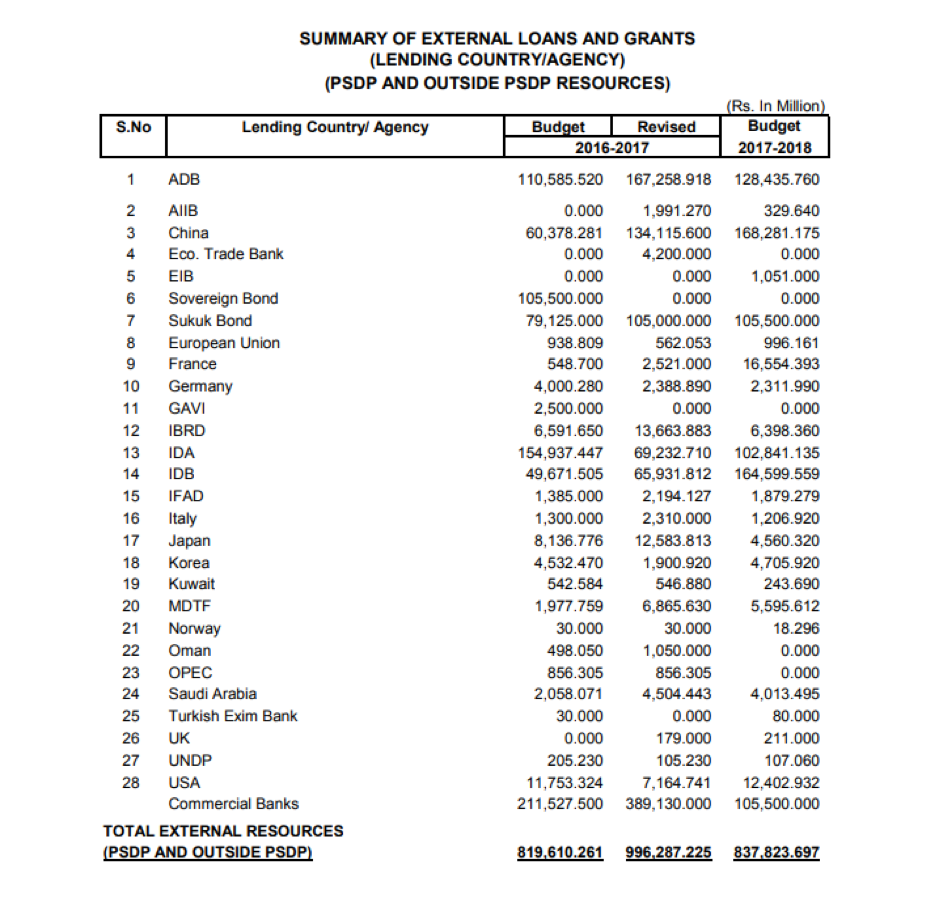

Pakistan’s financial and economic position has ensured that it is dependent, to a variable extent, on external state actors and multilateral lending institutions. This dependency has changed character because of massive capital and fund infusions by China and its state institutions under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor arm of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). A summary of external loans and aid grants is given in the table below:

Source: Estimates of Foreign Assistance, Federal Budget 2017-18, Government of Pakistan Finance Division

The Chinese budgeted amount for 2017-18 clearly exceeds that of the United States. Furthermore, the State Department in a briefing on January 4 confirmed that security assistance to Pakistan was being put on hold. But the specifics, such as the exact amount and which subheads of the security aid were being put on hold, were not given. Rather than acting as a leverage, this may enhance Pakistan’s sole dependence on China. While the United States can still hurt Pakistan through the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) where Pakistan is under review, the Pakistan Army will not be deterred. The consequences of any financial deprivation with its cascaded effects on the economy will be borne largely by the civilian and political authority in power, not the military. Secondly, the Pakistani Army has become the chief recipient of arms manufactured by the Chinese, which has further mitigated its dependence on U.S. security assistance.

Pakistan’s Calculus

Together this implies that first, Pakistan has no incentive to back U.S. objectives in Afghanistan, the most important of which is the creation of a stable Afghanistan. Second, the United States has very little leverage to influence Pakistan’s security policy with respect to Afghanistan. Finally, as one of the more important non-military measures, the FATF-imposed costs on the economy will not affect the most important state element—the security establishment within Pakistan—and it may escape the most serious consequences of that action. In essence, the strategic rationale for Pakistan to desire a politically-divided Afghanistan that is not in control of its territory is stronger than the concern about vulnerabilities that the United States may exploit.

Views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the organizations with which he is affiliated.

***

Image: Al Jazeera English via Flickr

Editor’s note: To read this article in Urdu, please click here.