On November 5, 2018 Rear Admiral (retd.) William McQuilkin assessed Indian maritime strategy in the Indian Ocean Region, and strategic options for greater Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA), sea control, and power projection. Given the current Sino-Indian crisis and consideration of Indian options, SAV is republishing this article with permission from the Hudson Institute’s South Asia Program, originally available at https://www.southasiaathudson.org/blog/2018/11/5/strengthening-the-indian-chakravyuh-optimizing-indias-strategic-advantages-in-the-maritime-domain.

The long and fascinating five thousand plus year history of India is also an important part of the story of civilization itself. One need only to look at the sophisticated prehistoric Indus Valley civilization that rivaled or perhaps surpassed those of ancient Egypt or Babylonia. Or the ruins of the great temple complex Angkor Wat in Cambodia whose stone reliefs depict the story of the great Indian epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. These scenes of history repeat themselves in the many Hindu and Buddhist temples and inscriptions throughout much of Southeast Asia and beyond. Much of the spread of these Indian cultural influences were the result of India’s seafaring history.

India’s maritime traditions date back to ancient times and certainly by early Roman times east-west trade patterns had emerged riding on the monsoon trade winds. Indian dhows once plied the waters of the Indian Ocean from the Red Sea, to Oman, Gujarat, and the Kerala coast. The ancient Roman trading port of Muziris has been located on the Kerala backwaters in Southern India along with Roman coins and amphorae. It would appear that lots of Roman sesterces (ancient Roman coins) went to buy Indian pepper and other spices.

Today, as the silk and spice routes are returning, would be a great time for India to revive its strong maritime heritage in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). It would also present an opportunity for the United States and its allies to assist India in expanding its maritime presence, capabilities, capacity, and maritime infrastructure in the Indian Ocean, thereby helping to preserve the balance of power and the rules-based international order in the region. This would provide regional partners with options to offset increasing Chinese influence as well as opportunities for the United States and its allies to increase cooperation and interoperability with the Indian Navy while assisting India in expanding its presence, capability, and influence in the region.

As China’s port infrastructure and naval presence increases in the Indian Ocean, so too does its influence. India realizes that it must respond to China’s naval expansion. India’s Minster of External Affairs has stated: “we consider it an imperative that those who live in this region bear the primary responsibility for the peace, stability, and prosperity of the Indian Ocean,” and Prime Minister Narendra has argued that “connectivity in itself cannot override or undermine the sovereignty of other nations.” India also well understands the delicate art of balancing, from Kautilya’s ancient writings in the Arthashastra, to the more modern era when China invaded Tibet, the balance of power has factored into India’s foreign policy.

Today, as the silk and spice routes are returning, would be a great time for India to revive its strong maritime heritage in the IOR. It would also present an opportunity for the United States and its allies to assist India in expanding its maritime presence, capabilities, capacity, and maritime infrastructure in the Indian Ocean, thereby helping to preserve the balance of power and the rules-based international order in the region.

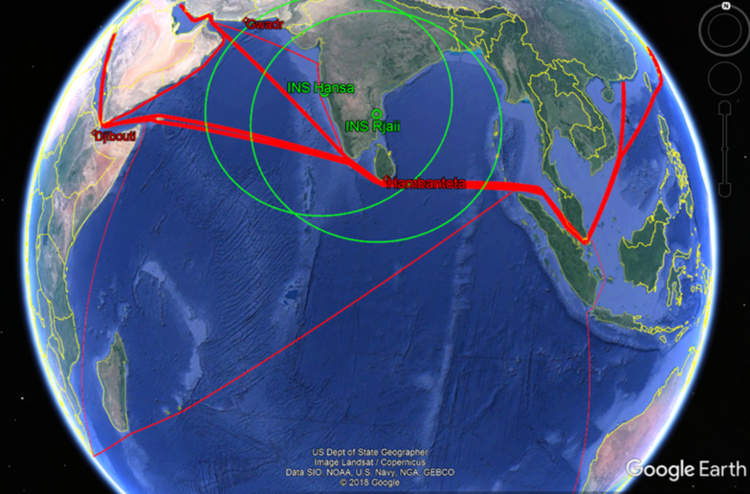

Indian naval and air capabilities operating from the subcontinent provide a solid anchor for Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA), sea control, and power projection near India. These are highly capable naval and air forces whom I have seen operate at sea. However, some adjustments in force posture and basing may be appropriate to respond to China’s presence in the Indian Ocean. Due to the sheer size of the IOR, the reach of forces based on the Subcontinent is insufficient to protect India’s interests throughout the region.

When President Xi Jinping first introduced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, China’s massive investment and infrastructure provision plan across Eurasia, many hailed it as a welcome economic advance toward Asian connectivity, promoting new supply and value chains. At the time, while the U.S. government appeared paralyzed and had little to say, India seemed alone on the world stage voicing skepticism of China’s plan and ultimate motives. In fact, India did not attend the 2017 two-day forum in Beijing on the BRI where President Xi feted other world leaders.

From India’s perspective, one can certainly understand its concerns about China’s expansion into the IOR with port facilities in Gwadar, Pakistan, Hambantota, Sri Lanka, investments in Bangladesh and Myanmar, and China’s first overseas military base in Djibouti. China’s significant investment and inroads in the Maldives is also a disturbing trend. India’s concern about encirclement with these Chinese-built port facilities and infrastructure, which were initially referred to as a “string of pearls,” is understandable given that these facilities could be easily convertible into dual-use facilities and that India’s southern and western flank are now exposed.

So, what potential options do India and its partners have to counter Chinese expansionism? The acclaimed author, Robert Kaplan, has said that “India can best project power at sea.” India, along with her strategic partners, must look for “places and bases” in the Indian Ocean from which to promote commercial interests, assure access, protect vital sea lines of communications (SLOCs), and to project power when and where necessary. Great power competition is nothing new in the Indian Ocean. The United States and the former Soviet Union jostled for position, power, and influence in this region throughout the Cold War. India has seen this movie too. Now is the time to revive India’s historic maritime traditions and establish or modernize port facilities from which to operate with its friends and partners.

India’s maritime force design and posture, to include basing, should flow from an overarching strategy and priorities. India’s top priority should be MDA and sea control in the Indian Ocean, anchored by and extending out from bases on the subcontinent. India currently has a lot of maritime capability and basing located on its west coast. This is understandable given the need to protect vital sea lanes, ensure energy security coming from the Persian Gulf, and to defend against Pakistan. However, this basing posture may not be optimized to monitor and counter China’s more recent forays into the Indian Ocean. With Nepal moving closer to China, China’s maritime infrastructure investments in Chittagong, Bangladesh and Kyaukphyu, Myanmar, India might be better served to put more emphasis on the Bay of Bengal area. Additionally, the Indian Navy may want to look at options to enhance resilience in view of China’s long range strike capabilities. For example, the ability to disperse capabilities from large bases like INS Vajrakosh and Kadamba. The U.S. experience under former President Reagan and former Secretary of the Navy John Lehman, the strategic homeporting strategy, may be a useful model.

India’s maritime force design and posture, to include basing, should flow from an overarching strategy and priorities. India’s top priority should be MDA and sea control in the Indian Ocean, anchored by and extending out from bases on the subcontinent.

In terms of the aforementioned strategy, once the anchor is set, India should look to improve and/or add forward bases to expand their reach and achieve specific operational and strategic objectives. The following recommendations on potential locations for India to pursue forward operating bases will be addressed in order of strategic priority.

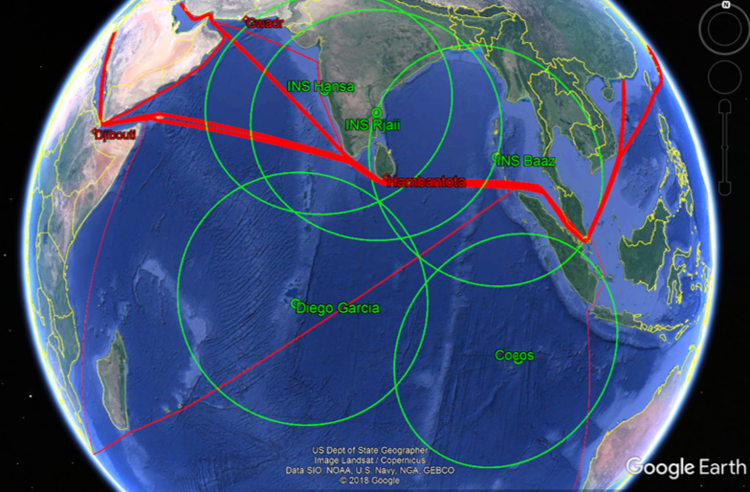

If China is the number one strategic priority, then expanding capability and operations in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands should be the top priority. First, these islands stand sentinel over one of the most strategic maritime choke-points in the world, the Strait of Malacca, through which flows the commerce and energy supplies that power the Asian economies. Previous Indian deployments of P-8I aircraft to these strategically located islands was absolutely the right move. More needs to be done in terms of infrastructure improvements to airfields and port facilities to support future deployments. These include airfield runway extensions and upgrades to accommodate India’s P-8I aircraft and improved ports and ship carrying capacity to facilitate having additional ships operating from the islands. India should also consider communications and sensor upgrades and the ability to deploy additional forces such as coastal defense cruise missiles (CDCMs) and air defenses. It should also be mentioned that these islands are Indian territory, so expansion is not contingent on negotiating access.

The other exciting feature of upgrading facilities on the Andaman and Nicobar islands are the opportunities presented for increasing interoperability and cooperation with strategic partners. The United States, India, and Australia all fly the P-8I. The Australians also have the strategically located Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean southwest of Indonesia. Imagine a future where these strategic partners could more routinely operate and fly P-8s together, using each other’s facilities with future logistics agreements in place, and covering vast swaths of the Indian Ocean. This would greatly improve MDA and operational and contingency response times to future incidents like the loss of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370. Additionally, with India’s acquisition of the MQ-9 B Guardian drones, intelligence, surveillance & reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities will be greatly increased. Operating the Guardian drones out of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands will be a force multiplier.

The potential to facilitate interoperability with partners extends well beyond P-8 operations. If India decides to pursue reciprocal basing access with the United States and Australia, shared use of Andaman/Nicobar, Cocos Island, and the U.S. base in Diego Garcia could be a win-win-win. Finally, Japan has expressed an interest in assisting India in upgrading the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. While projects currently being discussed are rather modest, this could grow to more important infrastructure investments to balance China’s BRI.

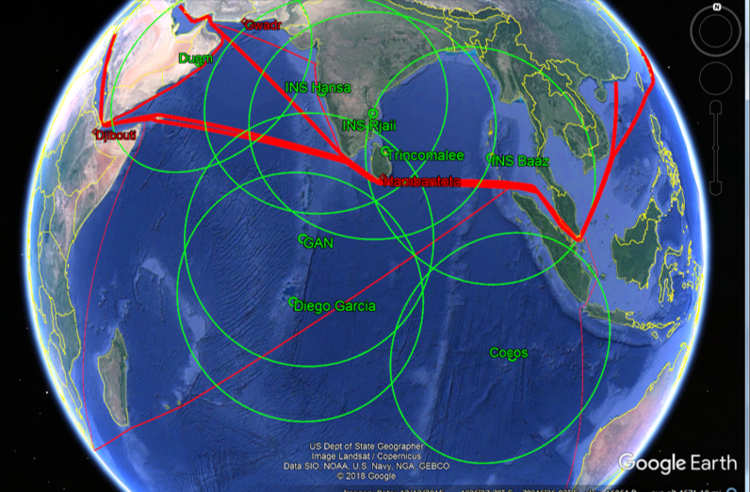

The other potentially important overseas basing opportunity, working our way west in the Bay of Bengal, would be the port of Trincomalee in Sri Lanka. Trincomalee is one of the finest natural deep water harbors of the world. It would be perfect for operating ships and submarines out of. India already has a commercial presence in Trincomalee managing oil tank farms and has been seeking to expand this presence. An Indian Navy presence in Trincomalee would be useful to balance Chinese access to (and virtual control over) of the Sri Lankan port of Hambantota. It would also increase Indian naval presence in the Bay of Bengal, heretofore secure in terms of India’s reach, but now like much of the Indian Ocean, where a competition with China is underway.

Regarding the strategic importance of Trincomalee, it is useful to take a look at the historical significance of this port with respect to India. The British Navy’s East Indies Station was based out of Trincomalee during the second World War. It is also important to note that the strategic significance of Trincomalee is well known. The Japanese attacked the British Fleet at Colombo and Trincomalee in the spring of 1942. This was following the successful attacks at Pearl Harbor, Malaya, and Singapore. Churchill described the attack on Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) as one of the most dangerous moments of the war. He feared that if the Japanese took Ceylon that they could use it as a springboard to attack India. Churchill had said that if India fell, his government would have fallen, and that would have been the end. Regarding, Sri Lanka and the Bay of Bengal, Japan came this way in World War II—and China certainly knows this history.

Again, working west, the strategically-located Maldives Islands are also a location where the Indian Navy and Indian Air Force should seek more access. China has made significant inroads into the Maldives to include the construction and opening this year of the Sinamale Bridge linking the islands of Male and Hulhule. Additionally, increased Chinese investment and tourism in the Maldives accounts for a significant source of income and influence.

The Indian Navy has a history of operating from Maldivian waters to assist the Maldivian military in exclusive economic zone surveillance and patrols. With India’s history of operating closely with the Maldives in counter-terrorism, the provision of light helicopters, and joint patrols, etc., and with the Maldives gravitating closer into China’s orbit, India would be well served to increase military-to-military engagement as well as a continued push toward gaining access to facilities. Due south of Male, the capital of the Maldives, is Gan in the Addu Atoll and the sight of an important strategic airbase, held by the British until 1976. This would still be an attractive naval and airbase. From the Indian Naval base of Kochi on the southwest coast of India it is approximately 506 nautical miles. Having a small naval facility in Gan could reduce response times for contingencies in this part of the Indian Ocean, but more significantly, would extend the reach and endurance of Indian maritime patrol aircraft. This could greatly enhance India’s MDA.

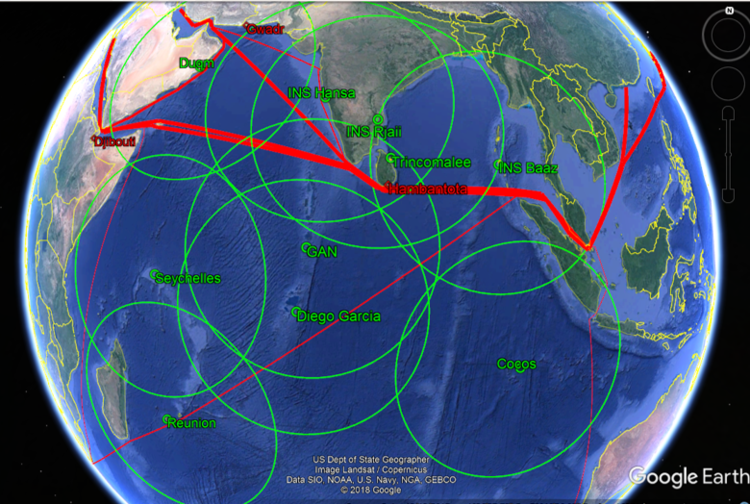

The Southwest Indian Ocean also presents strategic opportunities for India and its strategic partners. Looking towards 2025 and beyond, there will be an increased interest by both Asian and Western powers in East Africa as the reintegration of South Asia, East Africa, Southwest Asia, Central Asia, and East Asia continues.

Duqm, Oman is another interesting location for India to consider as a future logistics hub. India has lengthy historic ties to Oman, stemming from the maritime trade mentioned earlier in this article and also from the colonial era when the Sultanate of Oman became a British Protectorate. Duqm’s strategic location in the North Arabian Sea but well outside the Persian Gulf and the attendant security concerns of the Strait of Hormuz mark it as an ideal way station from which the Indian Navy can operate. This would give the Indian Navy additional flexibility and options in ensuring the security of vital energy supplies as well the protection of the large Indian diaspora in the region.

Beyond being a potential logistics hub, Duqm is well placed to extend Indian MDA and perhaps more importantly, from an Indian perspective, for power projection and sea control against Pakistan. Duqm would also provide potential training opportunities with U.S. forces transiting to or from the Persian Gulf. Duqm could be an important addition to the U.S.-India cooperation agenda.

The southwest Indian Ocean also presents strategic opportunities for India and its strategic partners. Looking towards 2025 and beyond, there will be an increased interest by both Asian and Western powers in East Africa as the reintegration of South Asia, East Africa, Southwest Asia, Central Asia, and East Asia continues. The shipping traffic bound for Asia around the southern tip of Africa, the Cape of Good Hope, has increased in recent years, stemming from ships originating from West Africa and South America. Additionally, there are purported to be large oil and natural gas deposits in East Africa to include offshore assets. Increased interest in the oil and gas sector here closer to Asia’s expanding economies may well increase the strategic importance of this area.

Potential overseas operating bases worth exploring in the southwest Indian Ocean include Madagascar and Port Victoria in the Seychelles. Madagascar has major seaports at or near the critical Mozambique Channel. Additionally, in March 2018 Indian President Shri Ram Nath Kovind visited Madagascar seeking greater cooperation in the maritime domain, to include cooperation in sustainable fishing and blue economy development, as well as the potential for greater cooperation with the Indian Navy and Coast Guard. Port Victoria in the Seychelles also looks to be a prime location for the Indian Navy to have a greater presence. India had previously signed an agreement with the Seychelles to build a military facility on Assumption Island that faced growing opposition in the Seychelles and has yet to be ratified. One way India may want to approach the concerns of Indian Ocean countries, such as the Seychelles, about pressure from China is to think about presenting this in terms of a scalable spectrum of options. This approach will be discussed in the conclusion.

It is important to note the strategic significance of France’s military presence in the Indo-Pacific. In the southwest Indian Ocean, French armed forces are divided between the Reunion and Mayotte islands. These forces include two frigates, two patrol vessels, one light landing ship and air assets. One of the primary duties of these forces is to protect France’s extensive exclusive economic zones (EEZ) in the area. This could provide an excellent opportunity for bilateral maritime security operations between India and France as well opportunities to work together to build maritime capacity in the region. France, as a key ally of the United States, may provide opportunities for operational synergies and overlapping bilateral engagements between the United States, India, and France.

As great power competition returns to the Indian Ocean, India will be best served by having a web of “places” and “bases” from which its commercial shipping, navy, and air forces can operate.

As great power competition returns to the Indian Ocean, India will be best served by having a web of “places” and “bases” from which its commercial shipping, navy, and air forces can operate. As India seeks to increase access to key places and bases in the Indian Ocean a scalable, tailored approach to pursuing access could be taken based on the strategic value of the location and host nation willingness to grant access. This strategy might look something like:

- Access to existing facilities, routine port visits, exercises, and military-to-military engagement with everyone who will allow it.

- Targeted commercial investments in strategic locations that could evolve into dual-use facilities.

- Selective investments in combat support infrastructure including logistics, command and control, and sensors at strategic locations.

- Permanent basing access.

It is also important to acknowledge that the strategic value of a location will not always align with a host nation willingness to grant access, and that India will need to balance investments in base infrastructure with investments in the forces that would operate from it.

Another aspect of this to consider is that naval forces, by nature, are more diplomatic and less threatening than land forces. In the U.S. experience, the Middle East Force in Bahrain provide a good example. Initially, comprised of no permanently assigned forces, a small headquarters element and three to five ships deployed on a rotating basis, the footprint in Bahrain was rather small. Actual command was from a flagship, the USS LaSalle and not a building. Today this initial small footprint has grown to the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet.

With China’s massive investment in the BRI one can reasonably predict that China’s naval presence will continue to grow apace in the Indian Ocean. India will need to counter balance this increased presence. It will not have to match China symmetrically, but will have to create an environment where misuse of China’s power will be constrained by Indian and regional capabilities, thereby complicating China’s risk calculus. As India looks for strategic advantage in the Indian Ocean, a key component will be the strategic geography of the IOR, home field advantage, and India’s security partnerships. India understands this. As the Arthashastra pointed out centuries ago, the “circle of states” or “rajamandala” is alive and well today. India’s effort toward increased balancing and a more effective military strategy makes a lot of sense in these uncertain times.

***