Since the beginning of the 2001 NATO campaign in Afghanistan, the leading player in the political and security conflict has been the United States. But over time, Chinese engagement in Afghanistan has grown: from 2001 to 2013, China played a supportive albeit passive role in Afghanistan. Then, beginning in 2014, China began demonstrating a willingness to take on a more active leadership role.

Where does Afghanistan fit into China’s foreign policy? This article argues that a shift in China’s approach to Afghanistan can be traced back to four major events around 2012. These four forces combined to influence China’s increased attention towards Afghanistan starting in 2014.

Historical Ties

Since the 1990s, China has faced terrorism and separatism in its western Xinjiang province, predominately from the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM). ETIM has widely thought to have received training and financial support from groups in Afghanistan, but prior to 9/11, China was not working closely with any party in Afghanistan to counter this threat despite concerns about the Taliban’s link to Uighur militants. After 9/11, China saw an opportunity to publicly align its own terrorist fight against the ETIM with NATO and U.S. goals, and began to seek diplomatic support in confronting the issue.

In November 2001, for the first time, China linked the ETIM to Taliban activities at the United Nations. Later that year, China voted in favor of both UN Security Council resolutions 1368 (authorizing the use of force against Afghanistan and the Taliban) and 1373 (targeting terrorist financing). This marked the first time China supported U.S. military intervention since the end of the Cold War. Additionally, China allowed U.S. ships to stop in Hong Kong on their way to Afghanistan and closed its border with Afghanistan to prevent fleeing members of Al-Qaeda and the Taliban to escape through China. Ultimately, both the United States and the United Nations added the ETIM to their respective lists of terrorist groups.

Starting around 2003, China shifted its focus towards its growing economic goals in Afghanistan. As Robert Kaplan writes, the U.S. vision for Afghanistan was a stable country that is no longer a haven for extremists, while China’s vision revolved around its goal of securing natural resources. Thus, between 2003 and 2012, China engaged in only limited security engagement with Afghanistan while focusing instead on enhancing economic cooperation, mainly through Chinese-initiated projects. It was not until 2012 that the first sign of a shift in China’s Afghanistan strategy occurred when a high-ranking Chinese official visited Afghanistan—the first time since 1966.

A Shift in Engagement

Why would China, which consistently stresses its position of non-interference in other countries’ affairs, want to entangle itself in the complicated politics of Afghanistan, and why at this time? Four factors that emerged between 2012 and 2014 led to a change in China’s calculus, altogether guiding its broader strategic decision to increase engagement in Afghanistan’s political and security affairs starting in 2014.

Why would China, which consistently stresses its position of non-interference in other countries’ affairs, want to entangle itself in the complicated politics of Afghanistan, and why at this time? Four factors that emerged between 2012 and 2014 led to a change in China’s calculus, altogether guiding its broader strategic decision to increase engagement in Afghanistan’s political and security affairs starting in 2014.

First, the U.S. and NATO forces announcing in May 2012 their intention to begin withdrawing troops from Afghanistan forced China to pay more attention to the country. There was a recognition that China would be directly impacted by violence along its shared border with Afghanistan. In response to this new reality, in October 2014, China hosted the 4th Ministerial Conference of the Heart of Asia-Istanbul Process (an international platform to discuss cooperation among Afghanistan and its neighbors) in Beijing. This marked the first time that Beijing hosted any international conference related to Afghanistan. Other significant changes include increasing amounts of high-level bilateral engagement, Chinese meetings with the Taliban, the China-Pakistan-Afghanistan Dialogue, and the China-Pakistan-Afghanistan-United States Quadrilateral Coordination Group (QGC).

Second, the increased number of terrorist attacks inside China between 2012 and 2014 necessitated a hard look at the impact of Afghan instability on China’s internal security. Since the 1990s, most of the terrorist attacks in China had been limited to the western province of Xinjiang, but since the end of 2013, terrorist attacks began occurring in other areas. In October 2013, a car exploded at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. In mid-2014, three attacks occurred in the railway stations of Kunming and Guangzhou. Facing the threat of Afghanistan as a potential breeding ground for anti-China terrorism, Beijing stepped up counterterrorism cooperation with regional partners. In 2016, Afghanistan, China, Pakistan, and Tajikistan established a Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism (QCCM) to coordinate intelligence sharing, counterterrorism training, and capacity building. Outside of the QCCM, Afghanistan, China, and Pakistan have continued to meet to discuss joint efforts in fighting terrorism.

The third factor contributing to a shift in China’s Afghan policy was its increasing economic participation in South Asia, which led Beijing to recognize the link between regional security and its economic goals. In 2013, President Xi Jinping proposed China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While BRI does not currently pass through Afghanistan, China and Pakistan are considering expanding the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship BRI project, to Afghanistan. Additionally, China has pledged to invest $100 million of BRI investments in Afghanistan. CPEC, and BRI more broadly, would benefit from improvements to Afghanistan’s stability and successful political talks between Afghanistan, the Taliban, and Pakistan. China also recognizes that less violence in Afghanistan will decrease the threat that violence will spill over into existing BRI project areas.

Finally, China’s broader foreign policy evolution between 2012 and 2014, specifically with regard to BRI and the “March West” strategy, has led to increased Chinese involvement in Afghanistan. This is reflected in two 2014 initiatives: the first, when China appointed its first special envoy to Afghanistan, Sun Yuxi, who himself emphasized that the appointment of a special envoy “reflects China’s desire to play a more active role in international affairs.” And second, China significantly raised the amount of government aid it gave to Afghanistan, and for the first time offered military aid. In October 2014, China pledged $327 million in government aid to Afghanistan, amounting to more than what China offered from 2001 to 2013 combined.

China as a Regional Leader?

By 2014, these four factors led China to believe that playing a larger role in Afghanistan’s political and security realms was linked to its own national interests. China’s subsequent shift from economic cooperation to security engagement in the country reflects its commitment to this changing strategy. However, it is still unclear if China is willing to take on a significant leadership role in the region. This situation also begs the question: how can China continue to play an active role in the region’s security issues while remaining true to its principles of non-interference?

In order to continue its trajectory of actively promoting stability in Afghanistan, China should utilize the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) to encourage deeper cooperation on regional security. For example, it could work to renew interest in the SCO’s underutilized Afghanistan Contact Group. China should also continue to push for more regional security meetings, which increase mutual understanding and interdependence in the region. Although China’s role in the Afghan peace talks is likely to remain limited compared to that of the United States, it could optimize its limited role by encouraging more cooperation from Pakistan, China’s close diplomatic friend.

Most importantly, China needs to define what kind of role it hopes to play in the region’s future. It is still unclear what the state of U.S. troop presence will look like if the United States successfully negotiates a deal with the Afghan government and the Taliban. China has already been called upon by Maulana Samiul Haq (the “Father of the Taliban”) to play a larger role in the peace process. If the United States does withdraw, China may be looked at to be a more consequential actor in both regional security and dispute resolution in South and Central Asia. Thus, China needs to communicate that it understands the demands of this potential responsibility and that it can define and commit to its intended role in the region.

***

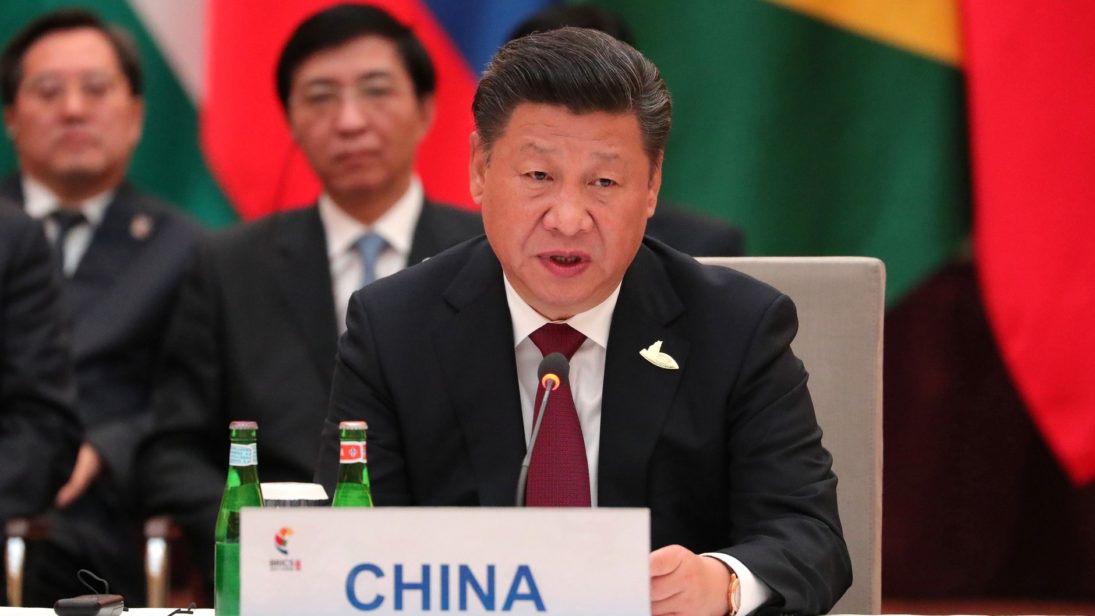

Image 1: The Kremlin via Wikimedia

Image 2: Regional Economic Cooperation Conference on Afghanistan