This year marks two decades since the Kargil conflict between Pakistan and India in 1999. A watershed event on the heels of nuclear tests, the occurrence of Kargil dismissed the common Cold War conception that conventional fighting could not occur between nuclear-armed states. 1 In short, Pakistan’s Northern Light Infantry (NLI) troops occupied the heights above Kargil, a small town in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, igniting a limited war that eventually resulted in a return to the status quo ante. Pakistan’s conduct during Kargil has had lasting legacies for the country’s domestic political dynamics, the trajectory of Indo-Pak relations, and Pakistan’s image in the international community.

Pakistan’sBehavior during the Crisis

The Kargil conflict emerged from a disconnect between Pakistan’s civilian government and military leaders: the prime ministers of Pakistan and India at the time, Nawaz Sharif and Atal Bihari Vajpayee, had recommenced dialogue between the two countries in 1998. 2 At the same time, a handful of Pakistani army generals were apprehensive about the détente policy that the civilian elected leadership was pursuing. Galvanized by Operation Meghdoot that led to India’s annexation of the Siachen Glacier in 1984, four Pakistani generals activated a plan. The army had given past Pakistani leaders (namely General Zia ul Haq and Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto) similar proposals for an infiltration in the Kargil region in the 1980s and 1990s. However, the plans had been shelved at the time, and some analysts believe that the blueprint of attack was revived when Pervez Musharraf was appointed chief of army staff in October 1998. Musharraf and the generals titled their operation “Koh-e-Paima” (“Mountaineer”), and intended to avenge the Siachen incident, resuscitate the lagging insurgency in Kashmir, and internationalize the Kashmir issue.

Unbeknownst to the civilian government’s foreign policy apparatus, other senior army commanders, and perhaps to even Nawaz Sharif himself—who as Pakistani journalist Ejaz Haider wrote, was deceptively briefed by the cabal of four generals—Pakistani soldiers were climbing the peaks of Kargil across the Line of Control (LoC) in early October 1998 as the government planned a momentous Pakistan-India summit in Lahore. 3 According to Nasim Zehra’s 2018 book From Kargil to the Coup, the scope and danger of the operation was not apparent to the Pakistani government until May 17th, 1999, but by this time it was too late — fighting was already underway and withdrawal could not occur quietly or easily. 4

Indian authorities at the time of the operation assessed that the trespassers were mujahideen. 5 However, it soon became clear that the infiltrating force was comprised not of civilian militants, but rather nearly entirely of NLI troops. Pakistan continued to use the cover story of militants and to let India believe this was the truth. The instigation of the conflict by Pakistan, as well as its covert nature, makes Kargil a case study with far-reaching implications for Pakistani decisionmaking and crisis behavior.

AHouse Divided

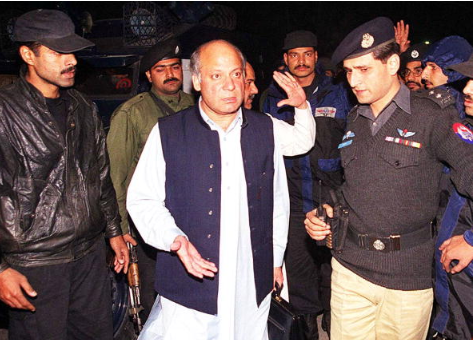

Kargil revealed a glaring disunity in Pakistani civil-military leadership — never had the chasm in decisionmaking been as apparent as it was during this conflict. To draw attention to this legacy of Kargil is not to contend that it was novel in 1999, but that the conflict exacerbated the civil-military disjuncture. A series of diplomatic setbacks, including President Bill Clinton’s demand that Sharif use his influence to withdraw the “militants” from Kargil unconditionally, created the perception that the civilian leadership – and Sharif in particular – did not prioritize national interest. 6 Amidst the blame game that colored the end of Kargil coupled with public disillusionment, when Sharif preemptively moved against the military, he was countered by a coup that resulted in General Musharraf coming to power. 7 Far from facts on the ground, Sharif was the scapegoat blamed by the cabal and opposition parties for compromising the army’s winning position with his Washington “sell out.” 8 Years later, in his memoir In the Line of Fire, Musharraf delineated his justification for takeover when he wrote, “It was in dealing with Kargil that the Prime Minister exposed his mediocrity and set himself on a collision course with the Army and me.” 9

The planners of Kargil made gross misjudgments in underestimating India’s response and overestimating the international community’s sympathy for Pakistan….These miscalculations were political judgments that could have benefited from civilian inputs.

Juxtaposed with the Lahore peace process, the Kargil war revealed two institutions standing at odds with each other. 10 To this day, the conflict raises a question of whether civilian leadership and the military have a common vision for India-Pakistan relations and highlights the dangers of fractured decisionmaking in Pakistan. The planners of Kargil made gross misjudgments in underestimating India’s response and overestimating the international community’s sympathy for Pakistan. 11As Dr. Negeen Pegahi explains, they suspected that Indian troops were fatigued by counterinsurgency efforts in Kashmir, that there was U.S. support for Pakistan after India tested nuclear weapons first, and that President Clinton’s personal life predicament would serve as a distraction and a window of opportunity. These miscalculations were political judgments that could have benefited from civilian inputs.

Indo-PakRelations

Sharif’s acceptance of his government’s role in jumpstarting the conflict, the withdrawal of Pakistani troops without any strategic gains, and international pressure made one thing abundantly clear — Kargil might have been a tactical success at first, but ended up a strategic failure. The blunder of Kargil changed the nature and trajectory of India-Pakistan crises and relations over the next two decades.

Sharif’s acceptance of his government’s role in jumpstarting the conflict, the withdrawal of Pakistani troops without any strategic gains, and international pressure made one thing abundantly clear — Kargil might have been a tactical success at first, but ended up a strategic failure.

Senior analyst Ashley Tellis reasons that one of Pakistan’s key takeaways after Kargil was that it should “continue seeking to calibrate the heat of the [Kashmir] insurgency” as the only pragmatic military option versus India post-Kargil. Analyses like this shaped the tone of future crises: both the Twin Peaks crisis of 2001-02 and the Mumbai attacks of 2008, among others, were conducted by extremist groups that Pakistan is accused of supporting. This year’s Pulwama episode saw Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) – a Pakistan-based militant organization that Western officials say continues to supply money, manpower, and expertise to militants inside India – claiming responsibility for a massive suicide bombing in the Pulwama district of Indian-administered Kashmir.

Since Kargil, Pakistan has faced the ebb and flow of censure from American and Indian policymakers for being a “safe haven” to terrorists. Even worse, this implication has made it easier for India to credibly lay blame on the Pakistani military as soon as terror attacks occur, however much Pakistan may deny it. For instance, in the throes of the Pulwama crisis in February, India credibly conducted the Balakot airstrikes without significant criticism from the international community despite a lack of concrete evidence that Pulwama was directed by the Pakistani military. Even if the government is not involved in perpetrating attacks, the fact that Pakistan is suspected of sponsoring certain militant proxies adds fuel to fire and helps India deflect international attention away from the Kashmir issue. 12 This strategic diversion has proven a successful tactic for New Delhi, as evidenced by the violence that continues to beset Kashmir to this day and the degree of international pressure on Pakistan to crack down on militant groups.

Moreover, since Kargil, even if progress is made between India and Pakistan, its longevity is dubious. Kargil had shattered the Lahore peace process, and in the years to come, crises like the 2008 Mumbai attacks would derail one of the most promising peace processes the two countries had ever experienced. Beneath any momentum for peace simmers a question: will another Kargil or attack come around and undermine breakthroughs achieved?

Inthe Eyes of the World

In the aftermath of Kargil, there was a paradigm shift in U.S.-India relations in view of the United States’ clear support for the Indian position.13 Although India was considered a regional pariah for nuclearizing the subcontinent just one year prior, Kargil transferred this label to Pakistan.14 In the years to come, rapprochement between India and the United States would only reach new heights—with an Indian-U.S. civilian nuclear agreement, and even a U.S. commitment to help India become a global power. Meanwhile, the fate of U.S.-Pakistani relations continues to hang in the balance, despite Pakistan’s cooperation in the global war on terrorism. 15

Since this paradigm shift and the diminution of its stature in the international community after Kargil, Pakistan has worked to expand its partners and stakeholders to elevate and reestablish its strategic significance in the international community. 16 Pakistan has also played the Afghan peace process to its advantage — knowing full well that the country has a key role in ending or settling the protracted conflict through bringing the Taliban leadership to the negotiating table. These past several months demonstrate that partners like China, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates increasingly have the connections, clout, and interests to play intervening roles in Pakistan’s favor.

Conclusion

A look back at the Kargil conflict of 1999 paints a mosaic of legacies for Pakistan. Going forward, Pakistan’s civilian and military leadership should craft a mutual understanding and vision for relations with India. Finally, although there may be a colossal extant trust deficit between India and Pakistan, Kargil is a reminder of the gravity of the Kashmir issue, and the reputational costs associated with adventurist behavior.

Editor’s Note: This piece is part of an SAV series on the enduring debates and legacies of the Kargil conflict twenty years later. Read the series here.

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

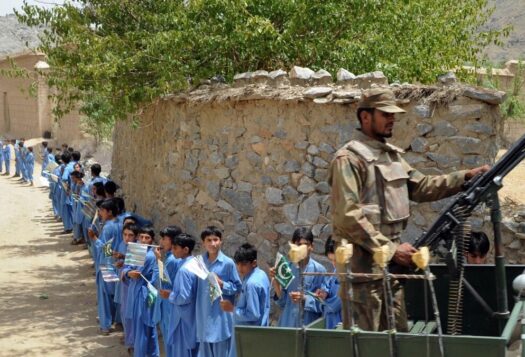

Image 1: bm1632 via Flickr (cropped)

Image 2: AFP via Getty Images

***

- Lavoy, Peter R. “The Importance of Kargil.” In Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia: The Causes and Consequences of the Kargil Conflict, 1. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Zehra, Nasim. From Kargil to the Coup: Events That Shook Pakistan. Sang-e-Meel Publications, 2018.

- Gill, John H. “Provocation, War and Restraint under the Nuclear Shadow: The Kargil Conflict 1999.” Journal of Strategic Studies, March 5, 2019, 701-26; Zehra, From Kargil to the Coup, 87.

- Zehra, From Kargil to the Coup, 153.

- Fair, Christine. “Militants in the Kargil Conflict: Myths, Realities, and Impacts.” In Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia: The Causes and Consequences of the Kargil Conflict, 231-56. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Shafqat, Saeed. “The Kargil Conflict’s Impact on Pakistani Politics and Society.” In Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia: The Causes and Consequences of the Kargil Conflict, 280-306. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Shafqat, Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia, 285.

- Zehra, From Kargil to the Coup, 328 and 340.

- Musharraf, Pervez. In The Line of Fire: A Memoir. London: Simon and Schuster, 2006, 137.

- Shafqat, Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia, 299.

- Rizvi, Hassan-Askari, Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia, 337.

- Fair, Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia, 250.

- Gill, Provocation, War and Restraint under the Nuclear Shadow, 721.

- Fair, Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia, 249.

- Fair, Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia, 256.

- Tellis, Limited Conflicts Under the Nuclear Umbrella, 66.