One year into U.S. President Donald Trump’s four year term, his administration is formulating its approach to the world, as evidenced by the Pentagon’s release of the National Defense Strategy (NDS) in January and the White House’s announcement of the National Security Strategy (NSS) in December. What makes these documents crucial for South Asia is the frequent mention of the “Indo-Pacific,” a term that refers to the maritime geographical construct hyphenating the 44 economies of the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. The current U.S. government has departed from the Obama administration’s “Rebalance to Asia” strategy by emphasizing the Indo-Pacific maritime domain. Thus, despite Trump’s “America First” policy, the United States appears to have a renewed interest in Asia that is predicated on the belief that it must counter China’s rise across Asia. However, there is danger in the United States’ attempt to undermine Beijing while providing to support to other Indo-Pacific countries. If the United States does not actively promote an architecture of economic and strategic partnerships in Asia, the NSS and NDS may exacerbate regional tensions without achieving much.

U.S. Engagement in the Indo-Pacific: Promises and Tensions

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was one of the primary vehicles for engagement with the economies of the Indo-Pacific under the Obama administration’s NSS 2015. President Trump withdrew from the TPP and his administration claims they wish to build “regional cooperation as well as bilateral trade arrangements” with Asian economies. However, it is unclear how the United States will engage economically with the Indo-Pacific in such a way that it counters Chinese economic influence. At the last Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in November, President Trump raised concerns in the region with his complaints about free trade while President Xi spoke about globalization. Also, at the moment, there is no indication of the Trump administration proposing its own regional trade agreement in the same vein as the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. Unless the United States demonstrates that it is fully committed to the region, both economically and militarily, Indo-Pacific nations will continue to simultaneously accommodate and maneuver both Beijing and Washington. This unfolded at the APEC summit, when Vietnam presented a diplomatic breakthrough by signing joint statements with both the United States and China separately.

On the strategic side, the NDS emphasizes the importance of deterring Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific while the NSS explicitly “[welcomes] India’s emergence as a leading power and stronger strategic and defense partner.” India’s status as a Major Defense Partner, initially conferred by the Obama administration, was formalized by Congress in the National Defense Authorization Act of the fiscal year of 2017. The NSS hints at the United States’ satisfaction that India has embarked on a major military modernization initiative under its “Make in India” policy with the aim of becoming a leading military power. However, there remains a clash between India’s expectation of the transfer of military technologies in defense deals and the United States’ hesitance to commit to the sale or transfer of technologies without India signing on to engage in meaningful military-to-military collaboration. If India is to be the United States’ closest strategic partner in the Indo-Pacific, then this tension in the relationship must be resolved and the pace of U.S.-India defense ties must pick up.

According to the NSS, the United States also seeks to “increase quadrilateral cooperation with Japan, Australia, and India,” indicating the Trump administration’s ambition to revive the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue—also known as the Quad—with these three Indo-Pacific democracies. In 2007, the Quad was briefly considered, but when China objected to the formation of the group, it was put on hiatus. Although Australia retreated from the Quad back then, the grouping saw a revival last year with Canberra back on board when officials from the four countries met on the sidelines of the East Asia Summit. Effective quadrilateral cooperation between these four countries would certainly help the United States counterbalance Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific. However, the United States needs to fully commit itself to the region to ensure the Quad’s success. It is unclear what steps the United States is taking to move the Quad to the ministerial or leader levels.

Implications of Trump’s “America First” Foreign Policy

Both the NSS and NDS are excessively focused on strategic competition. According to these strategy documents, the United States’ adversaries are China and Russia, who are “attempting to erode American security and prosperity,” as well as North Korea and Iran, who are destabilizing and repressive actors that represent a threat to America. However, by singling out these four countries, the United States might be bringing them closer together. China, Russia, and North Korea have voiced their displeasure at these documents, which they criticize for promoting a malicious “America first” strategy. Unfortunately, the Trump administration’s one-sided vision of securing American security interests at home and abroad is unlikely to assuage these concerns. While it is true that China has emerged as a key regional economic and military player in the Indo-Pacific, the ongoing crisis between the United States and North Korea is threatening to destabilize the region. At this point, Trump would do well to reach out to China to promote peace on the Korean peninsula rather than generating backlash from Beijing with the provocative NSS and NDS.

Looking Beyond “America First”

In view of the NSS and NDS, it is clear that the United States wishes to retain its presence and influence in Asia, albeit differently. These documents present American strategic policy in the Indo-Pacific as primarily focused on China’s rise. However, the United States should consider the security concerns of countries in the Indo-Pacific beyond its own “America First” foreign policy objectives. The failure to consider the strategic concerns of Beijing will only exacerbate underlying regional tensions. Thus, the Trump administration must broaden its view of the Indo-Pacific and consider what it means to engage with its allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific beyond the containment of Chinese regional and global hegemony.

Editor’s note: With the recent release of the National Security Strategy by the White House and the National Defense Strategy by the Pentagon, the Trump administration articulated its strategic priorities at home and abroad. In this four-part series, SAV contributors Monish Tourangbam, Hamzah Rifaat, Amina Afzal, and Pooja Bhatt analyze how these policy formulations may impact South Asia. Read the entire series here.

***

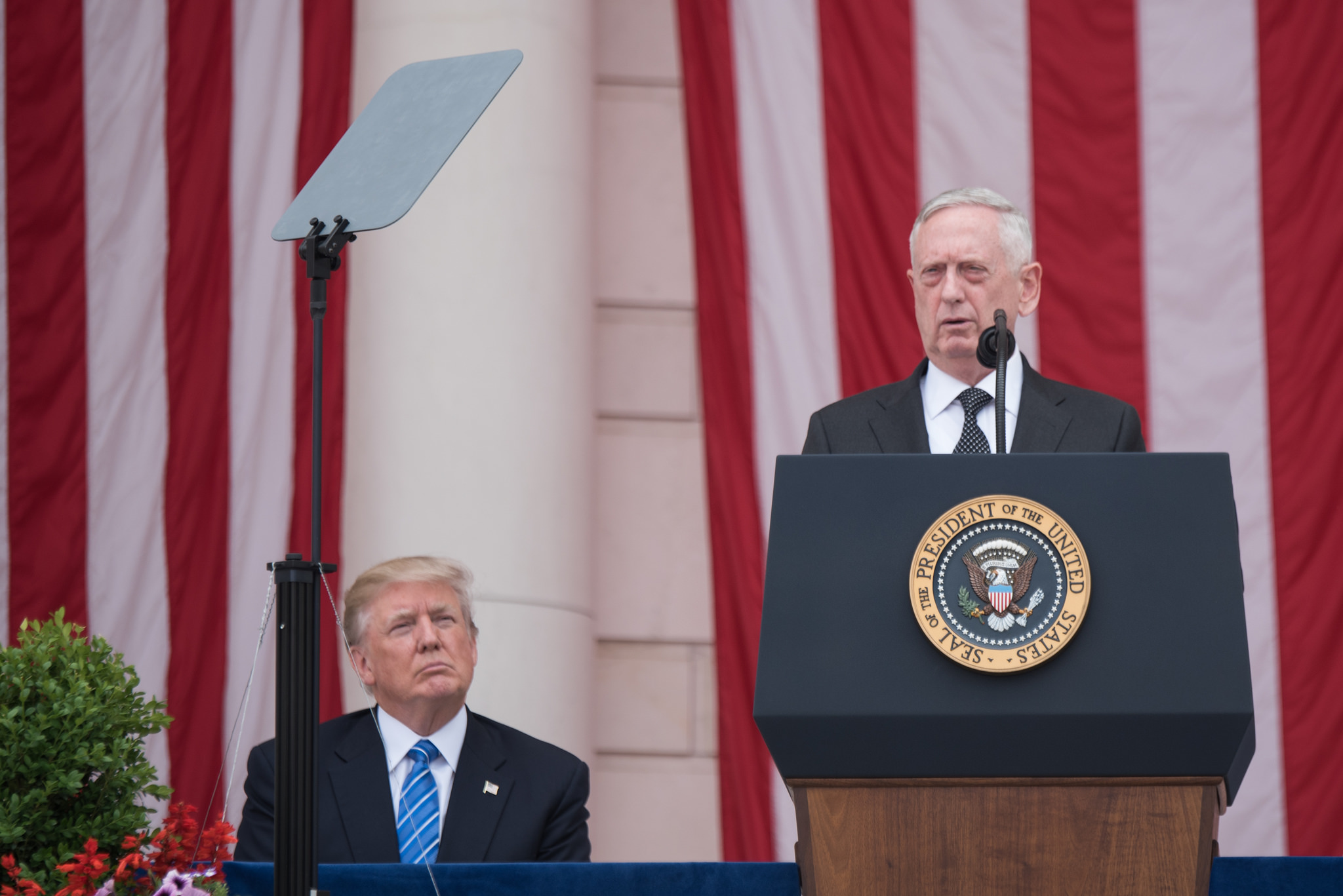

Image 1: Gage Skidmore via Flickr (cropped)