The military stand-off between China and India in Eastern Ladakh began in June 2020 and intensified their competition in multiple domains, from security to diplomacy. Yet, the leadership in China and India appear to have been restrained in referring to nuclear weapons capability in their public statements. Neither state threatened to push the nuclear button during the military standoff in 2021, which may be evidence that the nuclear dyad has been relatively stable compared to the India-Pakistan dyad. However, the absence of open-source evidence of nuclear signaling does not necessarily indicate that India and China have avoided it altogether.

This article will examine two instances of Chinese nuclear signaling vis-à-vis India: two videos that were released by Chinese state media in February and March 2021, each of which reference the military tensions at the border with India and include images of the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) carrying out preparedness exercises of nuclear-capable missiles.

China’s strategic exposure of its nuclear capabilities in these two videos was a short-term, tactical move intended to induce the disengagement of Indian troops along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) as talks between the two Himalayan neighbors stalled. In the long run, the videos suggest that China is strengthening its ability to target regional threats, including the border hostilities with India at the LAC.

PLARF Posturing: A Tactical Move or a Regional Strategy?

In another state-sponsored video released on February 19, 2021, we see PLARF soldiers pledging to defend Chinese sovereignty from foreign forces along with visuals of nuclear-capable Dongfeng missiles. The video was produced by state-affiliated National Defense Times and shared via the short video platform Bilibili.

In the long run, the videos suggest that China is strengthening its ability to target regional threats, including the border hostilities with India at the LAC.

In the video, the soldiers chant, “The majestic Karakorum saturated red fire sharpening edge. I am the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force motherland. I want to say to you that we hold a great weapon and must be determined to listen to the Chinese Communist Party’s command to sharpen the will to fight.” Since “Karakorum” is a term that the PLA uses for the region opposite eastern Ladakh that China claims, it follows that the pledge is referencing the border hostilities with India. This indirect reference to India is not surprising, since the PLA typically uses “Karakorum region” in internal propaganda while even Taiwan and the United States are not mentioned directly in PLA propaganda.

By releasing the two videos, China intended to put maximum pressure on India at a critical juncture in the 2021 military standoff. Although the intended audience of both broadcasts was primarily the Chinese public, Beijing also likely expected the Indian government and its intelligence apparatus to detect the publicly available videos. They were published at a time when India was negotiating complete disengagement of PLA forces deployed in Eastern Ladakh since the beginning of the military standoff in 2020. In particular, the DF-31AG exercise was broadcasted following the tenth round of military talks – a time when the talks hit a snag as the Indian side insisted on further withdrawal of the PLA forces. The timing of the exercise indicates that Beijing may have wanted to pressure India to agree to restore the status quo ante. However, it is unknown if New Delhi registered the DG-31AG exercise as a signal of resolve by the PLA or if it was meant to hint at the border tensions.

Chinese Missile Development: A Target on India’s Back?

Despite the lack of direct nuclear threats from Chinese leader Xi Jinping, China has carried out and strategically publicized military exercises of nuclear-capable missiles. On March 26, 2021, Chinese state television broadcasted the PLARF carrying out a preparedness exercise for the road-mobile missile DF-31AG variant. According to the broadcast, the exercise was carried out at negative 20 degrees Celsius at 4,000 meters. In the video, PLARF troops drive the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) DF-31AG missile on a Transporter Erector Launcher (TEL) to a particular location and prepare the missile for a test. The troops are wearing radiation protection masks (00:49) and checking the preparedness of the missile.

This March 2021 exercise is evidence that China is rethinking its regional targeting strategy. In 2017 and 2018, China officially displayed and consequently deployed the DF-31AG. The missile DF-31 and its variants are a new missile system which replaces the existing DF-4 missile system for regional targeting, according to the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists’ Nuclear Notebook. The DF-31’s range makes the missile ideal for regional targeting as the missile cannot cover the entire U.S. mainland. Instead, the DF-31 is suitable for addressing China’s regional deterrence gap, which includes India, Russia, and Guam.

There are also other clues that PLARF is particularly concerned about strengthening nuclear deterrence in the region, including vis-à-vis India. A new missile brigade, Brigade Base 647, likely carried out the test at Xining in Qinghai province. The exact location of the test was not advertised in the video. However, the mountainous terrain seen in the video is highly likely to be the higher altitude region of the Chinese province of Qinghai, which borders Tibet and is close to Ladakh. The location from where it was likely fired and the range of DF-31AG make the missile ideal for targeting India. If a DF-31AG missile was fired from Qinghai, the missile would not be able to even reach San Francisco. The missile is instead meant for regional targeting; it can cover the entire Indian subcontinent safely, including India’s outlying islands such as Andaman and Nicobar Islands and the Lakshadweep Islands.

The Future of Sino-Indian Nuclear Tensions

The two videos may not represent a nuclear-crisis-level signaling with India, but these official media platforms have made direct references to PLARF and its nuclear forces in the context of the standoff in Eastern Ladakh. China’s promotion of its nuclear-capable missiles during a military crisis shows that the leadership in Beijing may be willing to use coercive nuclear signaling in the future to achieve its objectives. This indicates a heightened risk of inadvertent escalation in future India-China conflicts, as distinguishing between an actual nuclear crisis and a military preparedness exercise can be difficult during a moment of heightened military tensions.

There is no evidence to prove that Indian political and military leadership has registered the missile tests discussed above. The Chinese leadership could be sending signals of escalation through mediums which may not reach the Indian leadership. If it is in fact true that the Indian leadership did not receive the signals China was sending, the prospects for inadvertent or accidental escalation may be grim.

The videos also suggest that China’s evolving regional nuclear strategy combined with the ongoing border tensions with India could complicate several contingencies. India could easily misread signals that China is sending to U.S. forces in Guam during a Taiwan contingency if the border hostilities with India were already trending downward. A crisis with Pakistan could cause India to become paranoid of China-Pakistan coordination, and thus become preoccupied with any signals China is sending from its nuclear forces in the region.

If it is in fact true that the Indian leadership did not receive the signals China was sending, the prospects for inadvertent or accidental escalation may be grim.

In sum, this analysis of Chinese nuclear signaling suggests that border tensions between India and China remain an understudied nuclear flashpoint in the complicated politics of the Southern Asian region. Both policymakers and scholars should work to ensure that there are open channels of communication between Indian and Chinese leaders that can be used to avert nuclear crises.

Also Read: The China Question in Indian Domestic Politics

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: Pangong Tso Lake via Wikimedia Commons

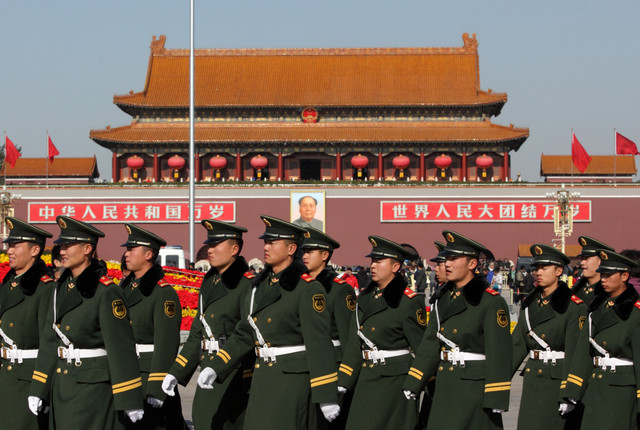

Image 2: Chinese PLA via Flickr