On the 53rd ASEAN Day this month, Pakistan’s Foreign Minister affirmed further strengthening ties with ASEAN nations in line with Pakistan’s Vision East Asia Policy. At a time when Islamabad is intent on pursuing economic diplomacy, reviving the policy, which focuses on deepening multi-faceted engagement with East and Southeast Asia, is a good bet for Pakistan. While the internal security challenges initially marred the progress of the policy, which was formally announced in 2003, revisiting it allows Pakistan to tap the substantial economic opportunities with East and Southeast Asian countries.

If diversifying economic partners is any metric, then looking east is imperative for Pakistan. The current government called to step up bilateral economic cooperation with South Korea, Singapore, Japan, and Malaysia earlier this year and expressed interest in upgrading Pakistan’s sectoral partnership with ASEAN to full partnership. Expanding economic and strategic ties with East and Southeast Asia helps Pakistan court foreign investments, boost employment opportunities, improve the balance of trade by amplifying exports, and bolster Pakistan’s economic clout and regional connectivity.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) has opened up avenues of regional integration and economic growth for Pakistan. While CPEC’s impact on strategic connectivity has primarily been understood through the lens of China’s access to Indian Ocean, the initiative’s ability to improve Pakistan’s interaction with countries to its East is understudied. However, while CPEC might help boost Pakistani exports to its east and invite investments, the triangular nature of the Pakistan-China-India relationship has also restricted Islamabad’s interaction with a number of East and Southeast Asian countries. Despite these constraints, Pakistan should pursue calibrated engagement with countries to its east and ensure that geopolitics does not constrict the potential economic gains.

While CPEC’s impact on strategic connectivity has primarily been understood through the lens of China’s access to Indian Ocean, the initiative’s ability to improve Pakistan’s interaction with countries to its East is understudied.

Expanding Economic Opportunities: Trading Ties with ASEAN and East Asia

Strengthening economic cooperation with East Asia helps Islamabad secure employment opportunities, and boost trade. For instance, the Memorandum of Cooperation signed with Japan last year for “Specified Skilled Workers” expands the work opportunities for Pakistanis in Japan. While Pakistan’s exports to Japan have decreased substantially from last year, owing to the fact that trading items are exported on basis of need-only, Pakistan could better access the Japanese markets by diversifying export goods and charting out consistent trading patterns. Similarly, as South Korea has designated Pakistan as a “priority partner,” moving forward on signing a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with Korea could help Pakistan address the non-tariff barriers and special tariffs for agricultural products that have impeded Pakistani exports’ access to Korean markets.

There are also untapped economic opportunities with Southeast Asian countries. For one, there is massive trade potential. While Malaysia is one of Pakistan’s top trading partners, the volume of trade between the two countries has been around USD $2 billion. Pakistan’s export potential under Pakistan and Malaysia’s 2008 FTA alone is more than double this at USD $4.6 billion. To realize this potential, Islamabad needs to address the trade balance favoring the Southeast Asian partners by augmenting the export flow to countries that ease the import barriers like Indonesia, which removed 30 percent of its import duties on 20 of Pakistan’s exports last year. Pakistan can also exploit the comparative advantage its exports, commonly cotton and textiles, enjoyed in markets in Brunei, Cambodia, Thailand, and Australia. There is also demand for Pakistani arms exports in Southeast Asia, evidenced by Malaysia’s interest in buying JF-17 Thunder fighter jets and anti-tank missiles from Islamabad.

There seems to be a similar interest among ASEAN nations in building ties with Pakistan as well. Recognizing Pakistan as important exporter of seafood and raw materials to Thailand, the two countries have been negotiating a FTA. Further, Thai companies are seeking investment avenues in the country as they recognize it as a significant trading partner. Likewise, appreciating the potential of Pakistan’s automotive market, the Malaysian automotive company Proton will open its first South-Asian production facility in Karachi by 2021.

Could CPEC help Pakistan’s Access to its East?

While CPEC is often viewed as an entry point for China to the Indian Ocean, it may also offer opportunities for Pakistan to access East and Southeast Asia. Two ventures of CPEC might hold this potential: land connectivity and Special Economic Zones (SEZs).

First, if Pakistan were to be allowed to trade via the Chinese ports, Pakistan’s access to Asian Tigers’ markets would be augmented with the shortened overland trade route resulting in less transit time and lower costs. China has granted Nepal access to some of its ports; a similar agreement could be drafted with Pakistan. Just as Pakistan’s Gwadar Port has enhanced China’s access to its west, Northwestern Chinese Ports, for example Qingdao port, can supplement Pakistan’s access to Northeast Asia. For instance, while it can take over twenty days at sea for Pakistani exports to reach Port Busan in South Korea from Karachi, it could take thirteen days if trade is done via land. 1

Second, the Special Economic Zones (SEZs) Pakistan is constructing under CPEC are critical for inviting foreign investments. For instance, while courting investments from Singapore, Pakistan referred to SEZ’s tax exemptions and other special incentives. Importantly, the Singaporean companies themselves showed interest in investing in CPEC projects. Similarly, citing improved trade procedures, Pakistan proposed establishing an exclusive economic zone for Korean companies as part of CPEC last year, to which the Korean companies showed interest. Although there has not been substantive progress on this, with a renewed focus on CPEC and moving ahead with the CPEC’s second phase – which focuses on SEZs – there may be more opportunities to draw in investment in the future.

The limitations to Pakistan’s Vision East Asia Policy

Pakistan’s engagement with East Asia is not happening in a vacuum, but in a contested region. The Asia-Pacific is a strategic theater of competition among multiple nations seeking to guard their economic interests. Thus, Pakistan’s close relationship with China and deteriorating ties with India may restrict its engagement with Southeast and East Asia.

For one, Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) concept, shared by the United States and other regional allies, is not so subtly positioned as an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in the region. As host to CPEC, the BRI’s flagship project, Pakistan confronts a dilemma in expanding ties with Japan. In the long run, Islamabad would not want to create concerns in Beijing as their strategic convergence goes beyond CPEC. Japan has also limited its relationship with Pakistan because of strategic ties with India through the Quad, evident from Japan’s support of India’s stance on Pakistan-backed terrorism. More explicitly, India’s Minister of Defense Rajnath Singh sought to “urge” South Korea not to invest into CPEC last year.

Pakistan’s close relationship with China and deteriorating ties with India may restrict its engagement with Southeast and East Asia.

Similarly geopolitically fraught is Pakistan’s relationship with Southeast Asian nations. As Beijing pursues greater influence in the South China Sea (SCS), littoral states in the region have faced growing territorial disputes with China and maritime tensions. Sensing the complicated geopolitics, any inclination towards China and its stance on the SCS by Islamabad could restrict expansion of ties with Southeast Asia, especially with countries like Vietnam and Indonesia, which take a more assertive stance against Beijing’s maritime position. Similarly, as evidenced by India’s “Act East” policy, India sees Southeast Asian nations as important trading partners, and further does not look at Islamabad’s full membership in ASEAN favorably. Pakistan’s ministry of Commerce and Textile cited Indian influence as the reason for Singapore blocking Pakistan’s ingress into the organization.

Reviving Vision East

While the constraints remain, Pakistan should look to expanding economic engagement to its east owing to the enormous trade and investment potential. Perhaps the way Asia-Pacific nations engage with China could be a lesson for Pakistan: ASEAN trade volume with China stands at USD $644 billion despite tensions in the SCS. Similarly, while Australia signed a defense deal with India, its trade surplus with China grew by 174 percent in March. Just as such countries have found ways to engage with China despite direct conflicts, Pakistan must likewise navigate its way into the Southeast Asian markets. Creative diplomacy practiced by Islamabad could help bolster its role as a player in regional issues, for instance, Pakistan could help Japan address its Hormuz Dilemma – concerns over the secure passing of energy supplies through the strait – and assist Tokyo’s mediation efforts in the Middle East, leveraging it to advance ties with Japan. Likewise, enhancing engagement with Southeast Asia will expand Islamabad’s economic footprint and political clout in the region, ultimately adding to its regional connectivity pursuits.

Sensing the intensifying turbulence in SCS, and growing China-India competition in South Asia in general, Pakistan ultimately would have to complement economic interaction with creative diplomatic signaling. Perhaps, however, an economically driven foreign policy may enable Islamabad to resuscitate Vision East Asia Policy despite the challenges.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

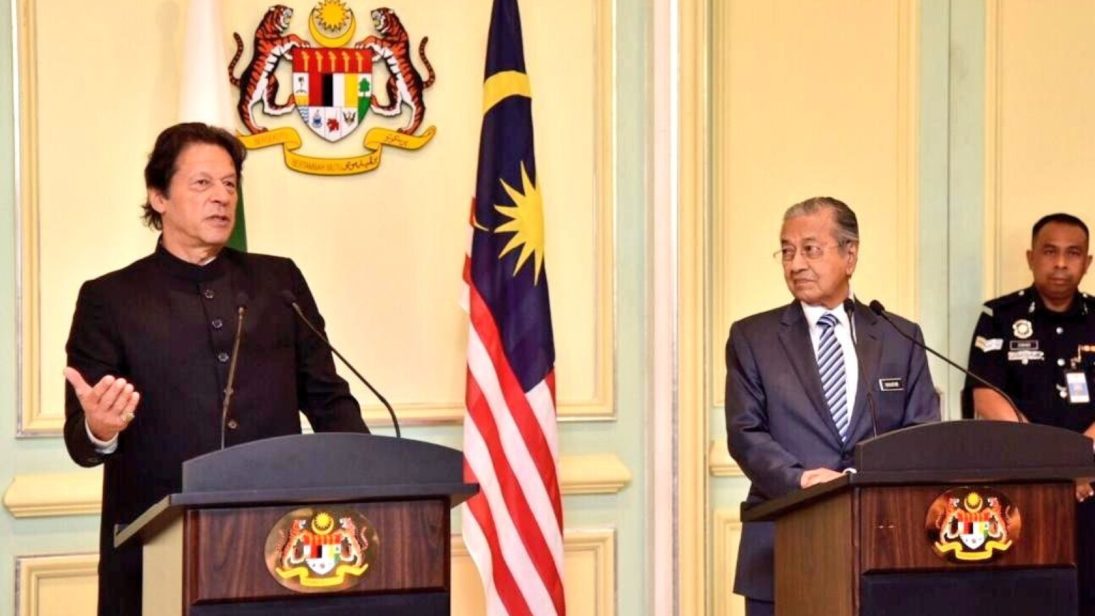

Image 1: Prime Ministers Office, Pakistan via Twitter

Image 2: MANAN VATSYAYANA/AFP via Getty Images

- This time was calculated with recent data on travel time by land from Gwardar to Kashgar and Kashgar to Shanghai, as well as shipping time from Shanghai to the port of Busan. The ship speed was measured at 12 knots.