The evolving India-Japan relationship– and in particular, the prospect of a nuclear deal –is worrying and causing geopolitical transformation in the Indo-Pacific region. The relationship between both countries has so far dwelled on the ascendance of Chinese power, regionally and globally, as well as India’s desire for a greater global role. It also brings both Asian partners closer to a new nuclear relationship as progress towards a deal symbolizes warming ties between the once-estranged democracies. This deal is not only a policy of containment against a common rival (China) but it could also create another wave of nuclear competition countries of the Asia-Pacific and South Asia.

Through a contentious decision-making process, passing over a half-century of missed opportunities, this alignment through nuclear agreement will be consequential for the region. The deal will serve as part of a broader effort to strengthen ties and counter a rising China.

Progress towards a nuclear deal is crucial between both countries for a future alliance, because the possibility of a truly profound strategic partnership between India and Japan depends on the nuclear issue. As a matter of national nuclear policy, the two countries are almost polar opposites when it comes to nuclear weapons and nuclear energy. Since the Fukushima accident, nuclear energy has been controversial in contemporary Japanese political culture.

Once the deal is finalized, Japanese companies will start exporting civilian nuclear technology and equipment to India. In the wake of the Fukushima accident and with the prospect of a nuclear deal, Japan faces a question: should it adhere to the old rules of abiding by the rules of nonproliferation, or, more realistically, try to revitalize its economy with much-needed revenue? For the time being, the Japanese government has focused on the second choice.

Interestingly, after India conducted Pokhran-II nuclear tests in May 1998, Japan that condemned India and participated in the international sanctions regime against it along with the United States and several other countries. The nuclear issue will still be a clash of values. Japan has always been uncomfortable with the Indian status as a non-signatory to the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, the Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty, and the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty.

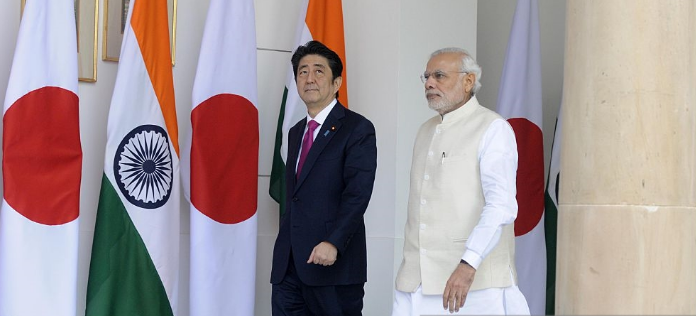

But the late-1990s proved to be transformative in Japan’s relationship with India. The relationship entered its contemporary phase of growth and normalization beginning with former Japanese Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori’s visit to India in 2000. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s decision to maintain relations with its strategic partner has boded quite well for India. He is known to be quite fond of India and imagines India and Japan at the “Confluence of the Two Seas,” bridging the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Indeed, negotiations on a nuclear deal resumed this year, but are still far from concluding. There still exists doubt if the civil nuclear cooperation agreement will work out for India and Japan. India has succeeded at signing similar nuclear agreements with other states, like the United States and Australia, for fulfilling its nuclear needs. However, the deeper problem in signing this agreement is rectifying Japan’s strategic unease with India’s nuclear status and ambition.

Both India and Japan already cooperate on security matters with a robust free-trade agreement. Though curiously enough, this bilateral relationship is still like a sideshow for both countries, as long as Japan does not accept India as a legitimate nuclear weapons state.

Japan’s economy’s being in the doldrums is one of the key forces driving Japan to sell its nuclear technology. India has planned to construct 18 more nuclear power reactors, and Japanese manufacturers are considering themselves as the strong contenders in an almost billion dollar market.

The deal, however, does face some opposition in India, where nuclear power has been derided as expensive and unsafe. Indeed, nuclear energy – and this deal – should be opposed in India because it is an unaccountable expansion of a technology, and risks exacerbating a nuclear competition between the countries of the Asia-Pacific and South Asia.

***