Language not only serves as a means of communication but also exerts a significant psycholinguistic impact on listeners. Specific choices of words can intensify or diminish the importance of any issue and shape perspectives passively. The nomenclature of South Asia’s strategic arsenal presents a unique case. Most non-South Asian nuclear states predominantly name their weapon systems using alphanumeric codes or acronyms based on technical characteristics (e.g., B61, THAAD). The nomenclature of South Asia’s strategic arsenal, however, is intertwined with the region’s religious, historical, and cultural context. India and Pakistan’s weapon naming conventions both work to shape public perceptions and indicate their evolving strategic postures, which have the potential to impact regional security dynamics.

The Psycholinguistic Impact of Nuclear Weapons on Statecraft

Religion and culture play a central role in shaping national identity in South Asia. Naming weapons along these lines helps political and military elites garner legitimacy for the country’s strategic posture, particularly from sections of the public with low literacy. Tying weapons system names to South Asia’s historical memory and religious signifiers strengthens nationalistic sentiments, such as reinforcing the two-nation theory, contributing to the perilous notion of a “holy war,” and highlighting the importance of military preparedness. These naming conventions can foster bias against the adversary and diminish bilateral trust.

By analyzing the cultural and religious symbolism underlying missile naming conventions, we come to understand the psychological salience missile names hold for India and Pakistan’s domestic politics and their nuclear dynamic.

Weapons names, in and of themselves, do not directly trigger an arms race or strain bilateral relations. Their role in shaping perceptions, however, adds to the overall environment where continuous weapons development is deemed essential for maintaining strategic parity. The media’s promotion of these names within the public discourse, coupled with a state’s own interests, can perpetuate an arms race mentality in the region. The naming conventions of India and Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal therefore amplify the perception of South Asia as an unstable and volatile region.

One might posit that the nomenclature of nuclear weapons should function as a potent deterrent, effectively conveying sentiments of scorn, wrath, and fear. However, such names gradually affect the collective psyche, leading to irrationality and indiscriminate zeal, which can influence state decision-making and public support for escalation during crises.

By analyzing the cultural and religious symbolism underlying missile naming conventions, we come to understand the psychological salience missile names hold for India and Pakistan’s domestic politics and their nuclear dynamic. Charting the evolution of missile names has the potential to reveal intentional shifts in India and Pakistan’s nuclear strategy.

Symbolism in Pakistan’s Arsenal

Most of the names in Pakistan’s missile arsenal allude to both historical legends of conquest and Islamic references, revealing a strategic choice to frame Pakistan’s offensive or defensive postures as founded in an Islamic and national source of legitimacy. Many of Pakistan’s early missile names carried offensive implications through their historical and religious associations. For example, the choice of the name Hatf (1992) for Pakistan’s missile series — meaning “Death” and derived from the name of Prophet Muhammad’s (P.B.U.H) sword — serves as a sharp warning, signaling that any attempt to violate Pakistan’s sovereignty will be met with iron hands. Similarly, the name Ra’ad (2007), meaning “thunder” in Arabic, symbolizes the Islamic concept of divine punishment. The Al-Khalid tank (2000s) was named after Khalid bin Walid, a Muslim commander who is believed to have been undefeated in his life, conveying a belief that Pakistan would be undefeatable. Missile and weapon system names with religious symbolism from Arabic, such as Ghazab (1963) (wrath), Zarb (2016) (to strike), Fateh II (2024) (conqueror), and Anza (1989) (to hit with a lance), showcase a conscious decision to portray Pakistan’s missile development as an offensive strategy.

Multiple missile names also symbolize Pakistan’s India-centric approach to its nuclear strategy, evoke national pride, and signal Pakistan’s assertiveness in the escalation ladder. Missile names like Ghauri (2003), Ghaznavi (2004), Abdali (2005), and Taimoor (2023) are named after individual invaders who defeated Hindu rulers in medieval India. The historical connotations of these names suggest readiness to use nuclear arsenals when necessary, in line with Pakistan’s “No-No First Use” doctrine, sending a clear message that any attempt to harm Pakistan will result in severe consequences. This approach may have been adopted due to Pakistan’s insecurity over the existential threats it perceives from India and the extensive involvement of military regimes in decision-making.

Meanwhile, missile names such as Tipu or Ababeel (2017) may represent a gradual shift in Pakistan’s strategic thinking toward a more defensive posture. Tipu was named after a Muslim hero who defended his homeland against foreign invaders; Ababeel is associated with a legend in which small birds protected the Kaaba against an army of elephants, highlighting Pakistan’s mindset to defend its small territory against a larger adversary like India. Looking at these naming decisions as one tool among many in shaping the perceptions of the public, the defensive orientation of the more recent Abadeel suggests an intent to signal a strategic shift to a more defensive posture – or at least to foster the perception of one. Does the more recent Abadeel reflect a realization that a defensive stance that lowers the nuclear threshold could be more effective in deterring India’s “Cold Start” strategy, thus raising the cost of limited conventional action within Pakistan’s territory?

Symbolism in India’s Arsenal

Similarly, the etymology of India’s weapon systems is drawn from a blend of Hindu religious mythology, history, culture, and strategic considerations. Historically, India’s naming choices often reflected a defensive posture and a commitment to a No First Use policy. For instance, the Prithvi missile(1996)— named after Maharaja Prithivi Raj, who defended his homeland against the Muslim invader Shahub din Ghauri — underscored India’s strategic emphasis on territorial defense. Similarly, names like Akash (2009) (sky) and Sagarika (2008) (seascape) conveyed the ability to observe every move and deter adversaries rather than pursue offensive strategies.

Recent names given to Indian missiles, however, hold more aggressive symbolism compared to previous names, potentially reflecting a shift in India’s strategic mindset. For instance, Agni Prime (2021) is named after the Vedic fire god Agni. By invoking the name Agni, India establishes a connection between its nuclear capabilities and its ancient religious heritage, emphasizing the destructive nature of these weapons through the name Agni. Similarly, Pralay (2022) (“destruction” in Sanskrit) and Trishul (2005) (the 3-pronged spear associated with Lord Shiva) symbolize religious elements that sanctify India’s capacity and divine justification to met out punishment. Another example is Astra (2019), meaning “a weapon created by God that can destroy the whole world.” Many of India’s missile names, such as Amogha (2016), Pranesh (2021), Pradyumna (2016), Rudram (2022), and Dhanush (2010), are derived from Hindu mythology, demonstrating the religious symbolism embedded in India’s nuclear arsenal.

The evolution of India and Pakistan’s missile naming conventions, and their deep connection with Islamic and Hindu beliefs and texts, demonstrates the subtle political power of language to support national narrative building.

Names rooted in Hindu and Islamic religious history have the potential to nurture expansionist narratives and strengthen concepts like Ghazwa-e-Hind (Battle of India) and Akhand Bharat (Greater India). The geographical depiction of Akhand Bharat as a borderless Indian subcontinent, highlighted in India’s newly inaugurated Parliament building, drew controversy about India’s strategic objectives across South Asia because it did not recognize the international borders of Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan.

The use of religious references to sanctify India’s strategic positioning as mirrored through divine narrative roughly aligns with India’s deviations from its nuclear doctrines and the growing public support for a First Use Policy. India’s increased investment in Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) and maritime capabilities has bolstered public confidence in a more aggressive posture. Military actions following the Pulwama attack in 2019 indicate that India, as a rising global power, seeks to assert itself.

Therefore, using such language to represent India’s newly developed missiles suggests a conscious shift in focus from the political use of weapons to deter adversaries to a narrative that legitimizes offensive use (or, “counter-force targeting”) among the educated and uneducated public. Though many other factors are likely involved in naming choices, India’s shift from defensive naming conventions to more offensive naming conventions aligns with the growth in public support for Hindu nationalism and India’s rise as a regional power.

The evolution of India and Pakistan’s missile naming conventions, and their deep connection with Islamic and Hindu beliefs and texts, demonstrates the subtle political power of language to support national narrative building, evoking battle history and religious associations for an implicit justification of the aggressive use of weapon systems. The name of a major, public-facing weapon system necessarily goes through multiple layers of approval and acts as a symbolic signal of the country’s strategic intent. By paying closer attention to missile naming conventions, we gain insight into how India and Pakistan build a domestic and international-facing narrative around their strategic posture.

Also Read: Understanding the Evolution of Missile Technology in Southern Asia

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: India’s Agni V via India’s Ministry of Defense

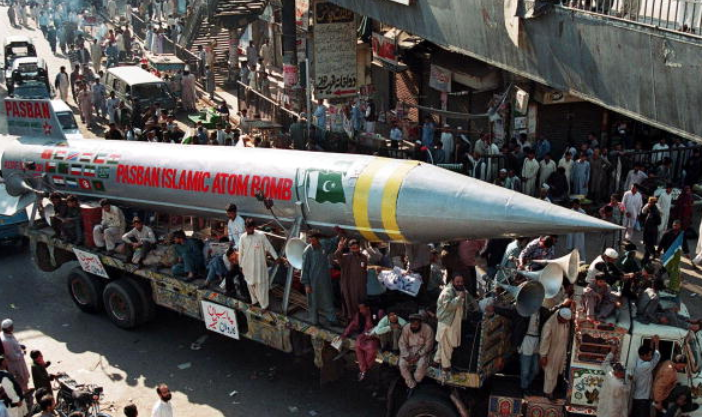

Image 2: A mock missile, dubbed the Pakistan Islamic Atomic Bomb, is paraded through the streets of Karachi in 1999 via Aamir Qureshi