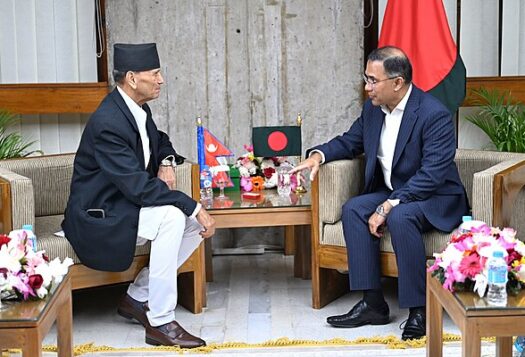

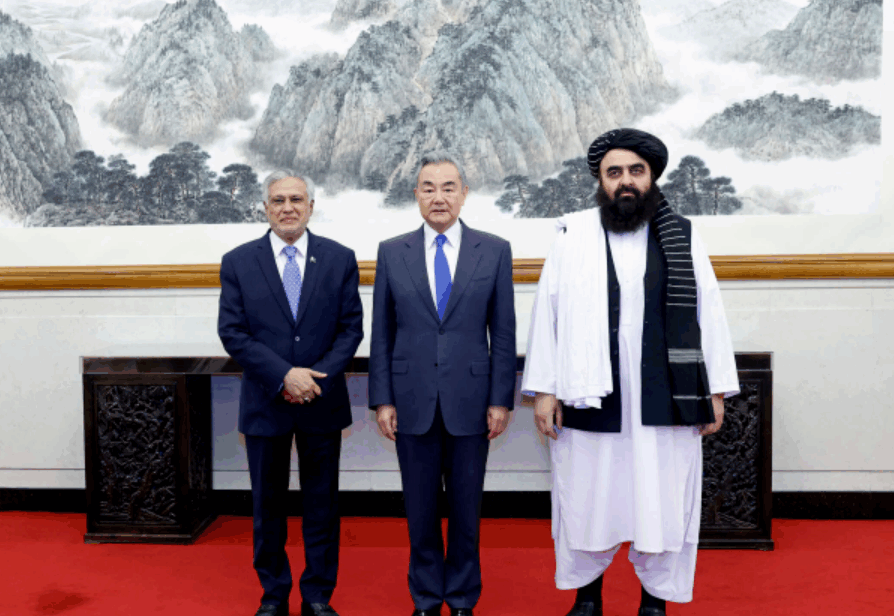

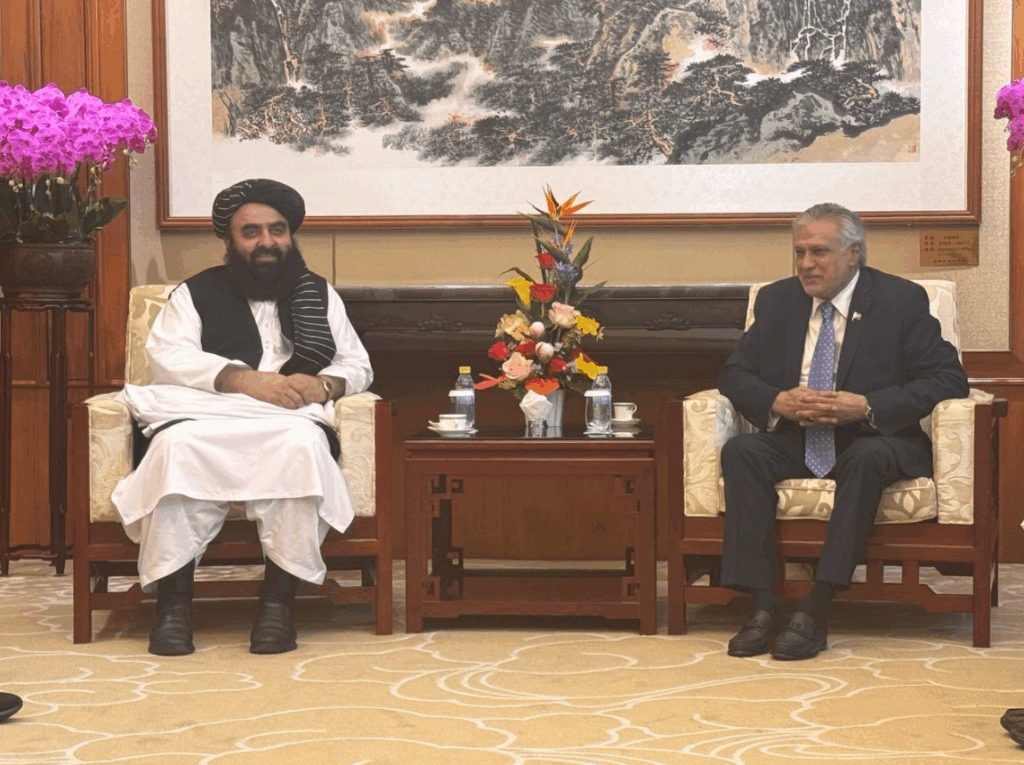

At the recent Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s Council of Foreign Ministers’ meeting in Tianjin, China, Beijing stressed the importance of stability in Afghanistan and underlined the need for multilateral efforts for the country’s reconstruction and development. Pakistani Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar echoed these sentiments. This was the latest in a series of signals over the last few months of a thaw between Islamabad and the Taliban, backed by China. Dar took a Pakistani delegation to meet the Taliban regime’s interim foreign minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi, to discuss bilateral issues in April while Beijing mediated a dialogue between Dar and Muttaqi during trilateral talks in China in May.

The May 21 trilateral meeting in Beijing came at an opportune time, given Pakistan’s need for stability on its western border and China’s desire to counter India’s influence in Afghanistan, especially after New Delhi’s recent outreach to the Taliban. The trilateral forum, which started in 2017, met after a one-year gap and the key tangible outcome was the elevation of the diplomatic representation of both Pakistan and Afghanistan to the ambassadorship level by the end of May, formally restoring diplomatic relations between Pakistan and the Taliban regime.

While this is a strong symbolic start, the China-Pakistan-Afghanistan trilateral can yield substantive and sustainable security and economic cooperation. Considering the members’ shared security stakes, the forum can establish narrowly focused and regionally-driven counterterrorism mechanisms against the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Eastern Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), and Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP). Chinese facilitation can also potentially mitigate Pakistan and Afghanistan’s border management and monitoring issues, such as Afghan refugees’ repatriation. Economically, the forum can uniquely leverage China’s aid, investment, and political backing to incentivize stable interdependence between Pakistan and Afghanistan despite political friction.

The May 21 trilateral meeting in Beijing came at an opportune time, given Pakistan’s need for stability on its western border and China’s desire to counter India’s influence in Afghanistan, especially after New Delhi’s recent outreach to the Taliban.

What’s Driving Chinese Engagement?

Beijing’s efforts to facilitate this Pak-Afghan dialogue are driven by both economic and strategic interests. For one, Beijing believes that connecting the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to Afghanistan would be lucrative and give it a foothold in the region, but this would necessitate a peaceful and stable Afghanistan that does not provide refuge to terror groups. Beijing’s proposed connectivity plans include major projects involving the Peshawar-Kabul Motorway, the Chaman-Kandahar-Mazar-i-Sharif-Termez Corridor, rail links for the Torkham-Jalalabad and the Chaman-Kandahar railways, and the Kunar River hydro project.

In addition to the economic benefits that China hopes to reap from the extension of CPEC into Afghanistan, Beijing is also likely eyeing cooperation to counter ETIM, which reportedly operated from Afghanistan’s Badakhshan and Nuristan regions in the mid-2000s and is seen by China as a threat to its Xinjiang region. Concerns about the group’s alleged cross-border activities have prompted Beijing to intensify diplomatic engagement with the Taliban government, seeking assurances that Afghan territory will not be used against China. In return, China has offered Afghanistan economic aid, infrastructure development, and integration into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

However, according to some experts, Chinese engagements with Afghanistan are largely an influence-building exercise aimed at projecting itself as a responsible global power in contrast to the West’s chaotic exit from the country in 2021. As the argument goes, the influence campaign is targeted at regional actors and global audiences to bolster China’s soft power and geopolitical credibility. However, the stakes are high for Beijing, with economic aid, diplomatic capital, and security cooperation interests hanging in the balance in a highly volatile environment and risks like potential attacks on Chinese interests.

Thus, China sees solving Pakistan-Afghanistan tensions as essential in two ways: doing so can secure stability along its Belt and Road corridor as well as prevent regional spillovers into Xinjiang. This recent trilateral dialogue exemplifies Beijing’s aim to position itself as a stabilizing force in the region, even as it remains cautious and transactional in its economic engagements with Afghanistan.

Pakistan’s Two-Front Strategic Headaches

In light of the kinetic escalation with India in May, the recent strengthening of India-Afghanistan relations has alarmed Pakistan, heightening its longstanding concern over the prospect of a two-front conflict. Pakistan worries that India could use Afghan soil to destabilize Balochistan and India’s rapprochement with the Taliban in recent months, including the first ministerial-level call between Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and Taliban Acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi, has again stoked these fears. Islamabad perhaps sees its recent efforts at a thaw with Kabul as a way to sway the Taliban away from India, though there is little evidence yet of a major shift in Afghanistan’s posture. In any case, these developments all the more emphasize the importance of the trilateral forum for Islamabad, especially in keeping the Taliban on side and preventing Afghanistan from becoming a wildcard in the India-Pakistan equation.

However, Islamabad’s own relationship with Kabul has been strained in recent months over the deportation of Afghan refugees, trade disruptions, and border clashes. The disagreements that haunt Pak-Afghan relations date back decades, beginning with the dispute over the Durand Line. However, their dynamic soured significantly after the Taliban’s takeover in 2021 over issues such as border management, resulting in skirmishes and even Pakistani air strikes into Afghanistan. These recent issues stem from the Pakistani state’s belief that the Taliban regime provides safe havens to terror groups, an accusation that Pakistan has levied against various Afghan governments.

Since 2021, Pakistan has repeatedly urged the Taliban government to take action against the TTP, but this pressure has not yielded meaningful action for two main reasons. First, the Afghan Taliban and the TTP have longstanding ideological and historical ties; second, the TTP pledged their allegiance to the Taliban regime when it took over Kabul. As a result, the Taliban have shown reluctance in lobbying for Pakistan with the TTP, often referring to the issue as Pakistan’s internal security matter. This has remained a major obstacle to trust-building because Pakistan views the TTP’s unchecked sanctuaries in Afghanistan as a direct threat to its national security, whereas Afghanistan perceives Pakistan’s demands as undue pressure.

Pakistan views the TTP’s unchecked sanctuaries in Afghanistan as a direct threat to its national security, whereas Afghanistan perceives Pakistan’s demands as undue pressure.

In this scenario, China’s attempted resolution of Pakistan-Afghanistan disputes, particularly as an actor that holds leverage over both countries, and Islamabad’s own two-front concerns vis-à-vis India and Afghanistan may have led to a temporary truce. This move by China could have implications for both counterterrorism cooperation and regional stability, though it would have to address Pak-Afghan distrust.

Room for Optimism and Reasons for Caution

The convening of the trilateral is just the starting point, not a cure-all solution to regional problems. For one, Pakistan and Afghanistan continue to have deep bilateral issues, such as border disputes and refugee management—preventing these legacy challenges from hamstringing pragmatic cooperation will be a test of the forum’s ability. Effective trilateral engagement would require the forum to move beyond symbolic diplomacy to develop structured, issue-specific mechanisms to achieve its objectives. This could include the establishment of a permanent working group on border management and refugee coordination, regular intelligence-sharing on cross-border militancy, and joint economic projects that tie Afghan stability to regional interdependence. As a first step, the forum could introduce confidence-building measures like keeping key border crossings operational with coordinated security protocols, formalizing a refugee registration framework, and initiating small-scale pilot trilateral development projects under CPEC or BRI.

For much of the tripartite agreement between the three countries to move forward, especially that focused on regional connectivity and economic cooperation, Afghanistan would have to address the acute security concerns of Pakistan and China. This could be done by offering conditional incentives like phased economic aid or infrastructure investment tied to specific security or governance benchmarks. Binding commitments would require outlining shared responsibilities and repercussions for non-compliance. For example, a trilateral border security pact with verification protocols or a joint refugee data-sharing agreement could transform political intent into accountable action, moving the forum from symbolic engagement to measurable outcomes. Such practical cooperation would lay the groundwork for a more resilient and action-oriented forum that secures the interests of all three countries and moves the region towards greater stability and growth.

Views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the positions of South Asian Voices, the Stimson Center, or our supporters.

Also Read: China’s Shifting Landscape in Afghanistan

***

Image 1: PRC State Council

Image 2: MFA Pakistan via X