It’s been almost two decades since India and Pakistan tested nuclear weapons in May 1998, less than a month apart. Still, the Lahore Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) of 1999 forms the basis for nuclear confidence-building measures (CBMs) between them. Though the rivals have agreed on multiple nuclear CBMs, these have been fairly ineffective in reducing tensions. While New Delhi and Islamabad’s lack of clarity over their nuclear doctrines and the purpose of their nuclear weapons could be a factor, nuclear CBMs have largely failed because they are unable to address the intricate linkage between nuclear and conventional issues in India-Pakistan relations. This issue has been acknowledged and conventional CBMs consequently negotiated, but the linkage between conventional and sub-conventional conflicts in the India-Pakistan context has been overlooked. As long as sub-conventional, conventional, and nuclear conflicts (or their prospects) remain connected, a broader framework comprising complementary conventional and sub-conventional CBMs will be needed in support of nuclear CBMs to instill any confidence in the relationship.

Using the Lahore MoU of 1999 as the foundation for nuclear CBMs, the two neighbors have subsequently discussed, reviewed, and monitored implementation in a series of expert-level talks. The most critical of these CBMs has been the bilateral consultation on nuclear doctrines. Apart from the Lahore talks of 1999, these consultations were held during the fourth round of the India-Pakistan Expert Level Dialogue on Nuclear CBMs in Islamabad in 2006. Discussions on nuclear doctrines are important to better understand each other’s nuclear redlines, postures, and deployment. But these consultations have so far failed in building sufficient confidence.

In India’s case, its declared doctrine lays out its nuclear redlines succinctly—India will retaliate with nuclear weapons “against a nuclear attack on India territory or on Indian forces anywhere.” India’s posture of massive retaliation suggests clearly that it will use strategic nuclear weapons for countervalue targeting if attacked by a nuclear weapon. However, despite the Indian government’s attempts to defend its nuclear doctrine, numerous domestic and international experts have criticized the doctrine, highlighting its shortcomings in meeting the objective of credible nuclear deterrence. Pakistan, meanwhile, perceives India’s declared doctrine as “simple ‘verbal posturing’ meant for diplomatic consumption only.” Interestingly, India’s foreign minister in 1999, Jaswant Singh, acknowledged that India would follow a different nuclear posture and deployment during war. Thus, there is confusion, especially from Pakistan’s perspective, on what India’s real nuclear doctrine entails.

Meanwhile, Pakistan, as an accepted state policy, prefers ambiguity over its nuclear doctrine, which only worsens the prospects of building any confidence with India. In recent years, the shift to full spectrum deterrence and the introduction of tactical nuclear weapons (TNWs) has exacerbated relations with New Delhi. Developing TNWs should be fairly simple for Pakistan as it claims to have nuclear devices of smaller yield and has test delivery systems of shorter range. Confusion, however, remains on their deployment and the requisite change in Pakistan’s nuclear chain of command.

The definition of TNWs by “use” requires them to be deployed close to prospective battlefields with their launch authority delegated to local commanding officers. Pakistan, however, has argued that its National Command Authority (NCA) continues to retain complete control over the decision to launch all of its nuclear weapons. Whether this is an attempt to merely address international concerns is unclear. Uncertainty remains on whether Pakistan has deployed TNWs in mated state close to prospective battlefields along the international border with India, or if they are stored in secret locations to be launched after NCA’s clearance.

This lack of understanding regarding each other’s nuclear doctrine, deployment, posture, threshold, and chain of command further diminishes the efficacy of nuclear CBMs. For instance, in the case of hotlines set up between directors general of military operations (DGMOs) and foreign secretaries, there is the question that “if there is a difference of opinion between the military and civilian officials within the two countries, whose views will prevail?” This suspicion grounded in political differences between India and Pakistan plays out at conventional and sub-conventional levels as well. The strong connection between nuclear, conventional, and sub-conventional conflicts further complicates the situation.

The inability of nuclear CBMs to account for links between nuclear and conventional conflicts has been flagged before. Consider a situation where India decides to launch a low-scale conventional attack on Pakistan on short-notice. Going by the statements of its army officials, this may invite use of tactical nuclear weapons by Pakistan, rendering all nuclear CBMs ineffective. As P R Chari argues, given that “the most realistic scenario for a nuclear conflict occurring in South Asia arises from the possibility of conventional conflict getting out of hand,” negotiations for nuclear CBMs and their implementation must be “intimately linked” to that of conventional CBMs.

To that end, India and Pakistan have held a parallel series of Expert Level Talks on Conventional CBMs. These conventional CBMs, however, have failed repeatedly with frequent violations of the ceasefire along the Line of Control (LoC). Perception in Pakistan is that India is not serious about conventional CBMs and that it would want “to keep its conventional-force supremacy intact.” But it is the direct link between conventional and sub-conventional conflicts that causes conventional CBMs to fail and renders nuclear CBMs ineffective. A majority of LoC ceasefire violations occur either to mask attempts to perpetrate sub-conventional war or in response to that.

Therefore, there is imminent need to establish CBMs that address concerns over terror attacks and use of non-state actors as proxies. India allowing a Pakistani probe team to conduct investigation on the Pathankot terror attack is a good start and the momentum built must be utilized for establishing CBMs on sub-conventional issues. Nuclear CBMs alone will not be successful until they are placed in a comprehensive framework with complementary CBMs that address conventional and sub-conventional threats between India and Pakistan.

*********

Eighteen years ago this month, India and Pakistan surprised the international community by testing nuclear weapons within weeks of each other. In the aftermath of the tests, the two countries formulated a set of confidence-building measures to mitigate risk and enhance strategic stability. But how effective have these initiatives been? Have they managed to achieve their objective or is a new approach needed? SAV contributors Arka Biswas, Sitara Noor, Sobia Paracha, and Tanvi Kulkarni will explore some of these themes in this series. Read the entire series here.

***

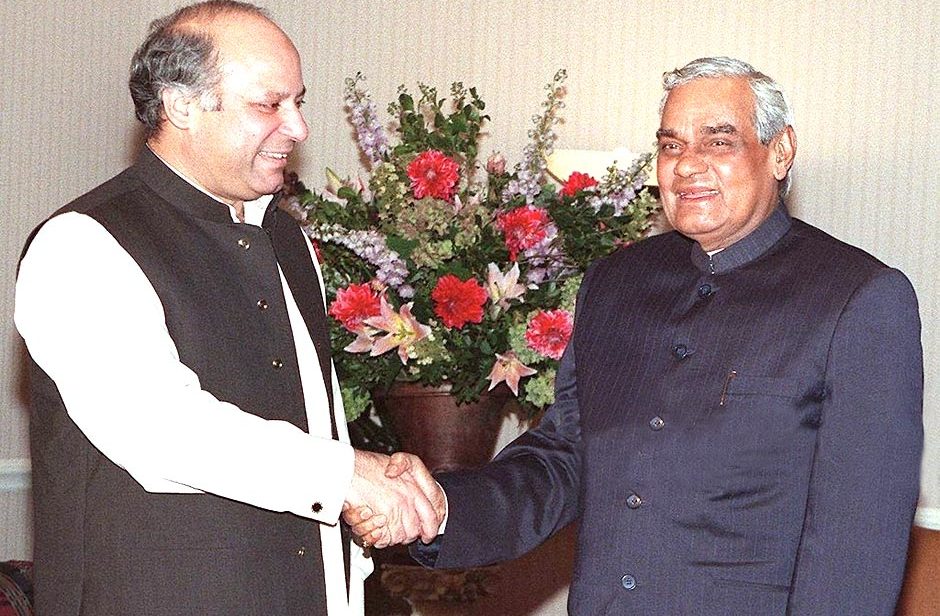

Image: Jay Mandal-AFP, Getty