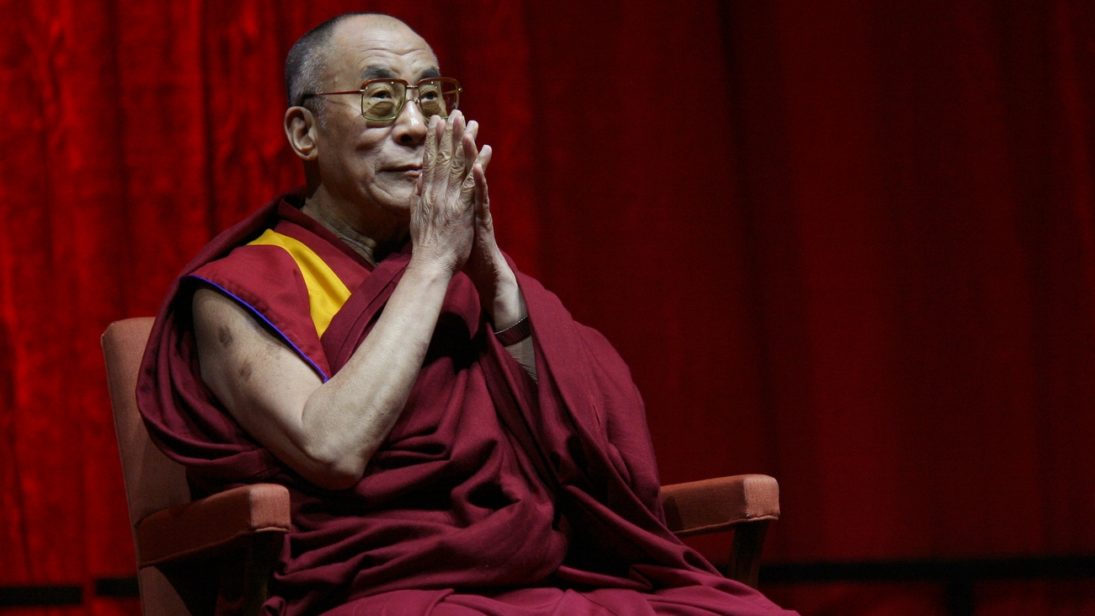

The Dalai Lama’s recent visit to India’s northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh prompted outrage from Beijing. The presence of the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader in the region that China claims in its entirety as South Tibet did not go down well with Beijing, which stated that the visit had “severely damaged” India-China ties. However, the move to allow the Dalai Lama to visit Arunachal Pradesh doesn’t point towards a major shift in New Delhi’s policy. In fact, it serves to reinforce an important message that New Delhi has been trying to convey over the last few years: India is no longer willing to play by Beijing’s rule book and will treat China the way it is treated by China.

The Dalai Lama’s trip, approved by the Indian government in October 2016, comes at a time when the elements of confrontation in the bilateral relationship outnumber those of cooperation. The relationship has been strained recently, due to China’s persistent non-cooperation on issues like India’s membership to the Nuclear Suppliers Group and China blocking India’s bid to get Pakistan-based militant Maulana Masood Azhar listed as a terrorist at the United Nations. Most recently, Beijing’s reluctance to accommodate New Delhi’s sovereignty-related concerns emanating from the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which passes through territory claimed by India in Jammu and Kashmir and the failure of the restructured strategic dialogue to find common ground on these issues has added to the unease. China’s deepening security relationship with Pakistan and Bangladesh, its investment in India’s periphery as part of the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative, and a growing trade deficit have also affected the bilateral relationship.

However, these recent irritants may only be serving to strengthen India’s resolve to continue to push China to pay attention to its demand for reciprocity. One way that India has done this is by repeatedly poking Beijing on its One-China policy. It was in 2010 that New Delhi refused to endorse the policy for the first time, removing it from a joint statement during the visit of former Chinese premier Wen Jiabao to New Delhi. All joint statements issued since then continue to skirt around the issue. Ahead of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to India in 2014, foreign minister Sushma Swaraj had stated: “For India to agree to a One-China policy, China should reaffirm a One-India policy.” Last December, India went one step further, ignoring protests from China in favor of setting up a Taiwan-India Parliamentary Friendship Association. Barely 10 days before the India-China strategic dialogue, New Delhi again ignored diplomatic protests from Beijing to play host to a Taiwanese parliamentary delegation that arrived in the country to interact with Indian parliamentarians. India’s move to allow the Dalai Lama to visit Arunachal Pradesh fits into this strategy. This was the Dalai Lama’s seventh visit to the region since arriving in the country in 1959, and China’s reaction to these visits has always been one of acute concern.

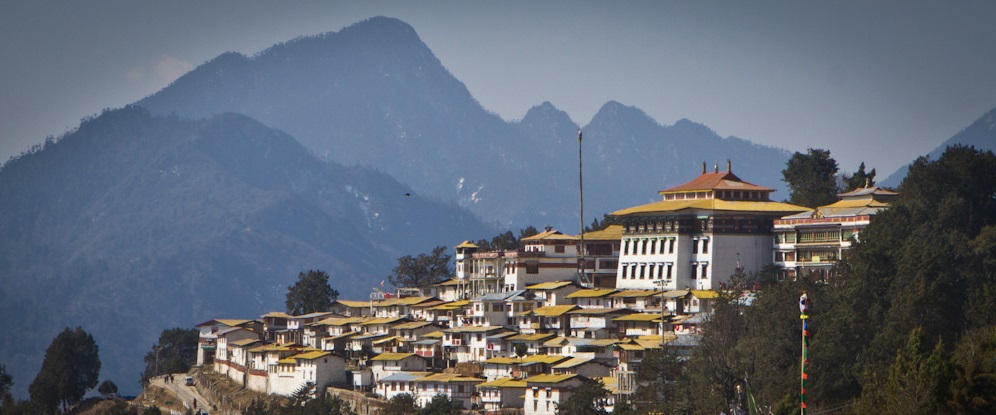

The Dalai Lama’s visit to Arunachal Pradesh remains a concern for China because the region houses the Tawang monastery, also called Galden Namgey Lhatse. It is the largest monastery in India, second only to the world’s largest, the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet. China fears that the Dalai Lama may ordain his successor in Tawang, which was also the birthplace of the sixth Dalai Lama. It wants to control future reincarnations of the Dalai Lama, as it did in the case of the Panchen Lama, to have tighter control over Tibetans. A Tawang outside China’s control does not fit into Beijing’s long-term strategy. Last month, Dai Bingguo, who served as China’s boundary negotiator with India between 2003 and 2013, suggested that the border dispute between the two can be resolved if New Delhi accepts Beijing’s claim over the strategically-important Tawang. In such a scenario, he said, Beijing may “address India’s concerns elsewhere.” Given the fact that Tawang provides India leverage over China, the offer was a non-starter.

New Delhi’s largely hostile reaction to China’s OBOR initiative, its efforts to counter China’s growing influence in its immediate neighborhood, and its willingness to forge closer relations with the United States, Japan, Australia, and Vietnam signal that India is no longer afraid to ruffle China’s feathers. And with China seemingly unwilling to address India’s concerns, relations are not likely to show significant change in the foreseeable future.

***

Image 1: Yancho Sabev via Wikimedia

Image 2: Sandro Lacarbona, Flickr