Introduction

On January 1, 2017, Indian and Pakistani diplomats exchanged official lists of the nuclear facilities located in their respective countries. According to news accounts at the time, this was the 26th such annual exchange of lists, pursuant to a 1988 bilateral confidence-building agreement not to attack each other’s nuclear installations. The fact that this exchange has been implemented without interruption, during periods of both calm and military crisis, makes it the most enduring nuclear confidence-building measure (CBM) on record in South Asia. At the same time, the banality of this exchange suggests that the agreement has little practical contemporary meaning for peace and security in the region.

When the non-attack agreement was originally negotiated, both countries’ nuclear weapons enterprises were relatively small and secretive, and fears (in Pakistan, at least) of a surprise attack on nuclear facilities had been rampant for several years.1 The agreement in theory helped allay concerns that nuclear facilities could be attacked purposefully, either by surprise or during a conflict, thus mitigating the potential humanitarian or environmental consequences that might result.

Over time, however, the agreement has proven to be merely symbolic, and its potential as a building block for enhanced confidence has remained limited. It was never backed by verification provisions, for example. During the period prior to 1998, in which neither state had openly declared its nuclear weapon status, it was widely assumed that both sides omitted nuclear-weapons-related facilities from their respective declaration.2 It is almost certainly the case today that neither side declares sites associated with nuclear weapons storage and operations, and perhaps other facilities as well. Any stabilizing influence the agreement contributed in the past has long since dissipated.3

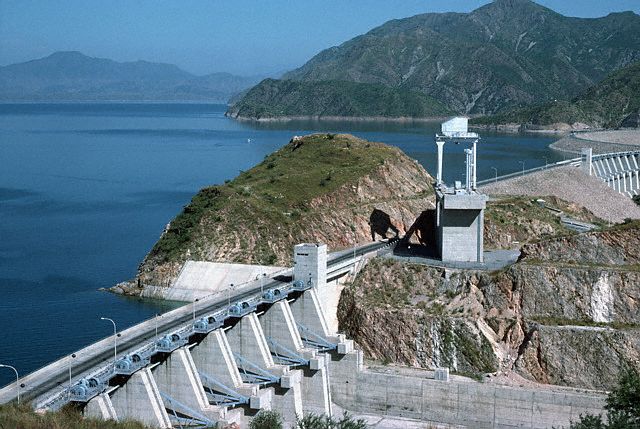

The lost promise of this long-standing CBM could be revitalized by modernizing the agreement to make it more relevant to contemporary strategic circumstances in the region. I propose to expand the agreement in two ways that build on the existing recognition by both states that they have a shared interest in preventing an incident at a nuclear facility anywhere in the region that results in a radioactive release. First, the non-attack provision should be expanded to other targets, destruction of which could similarly result in environmental or humanitarian catastrophe. For the purposes of illustration and suggestion, I propose that the agreement cover large dams, which are used for hydroelectric power generation and flood mitigation. The June 24 attack on the Salma dam in Afghanistan’s Herat province, attributed to the Taliban, highlights the importance of protecting such critical infrastructure. Second, in recognition of the potential for non-state actors to do as much damage as state actors, the agreement should establish a mechanism to share information about terrorist threats to facilities covered by the agreement.

Augmenting the Non-Attack Agreement

Before examining the rationale for the proposed expansion of the non-attack agreement in greater depth, I will first address how the text could be amended to effectuate the two changes proposed above.

To expand the scope of the agreement to include large dams, three additions would be required. First, the title of the agreement would need to reflect the broader coverage, such that it could become, for instance, The Agreement on the Prohibition of Attack Against Nuclear Facilities and Certain Critical Infrastructure.

Second, paragraph 1(i) could be amended to reflect the expanded scope of the agreement. Paragraph 1(i) stipulates:

Each party shall refrain from undertaking, encouraging or participating in, directly or indirectly, any action aimed at causing the destruction of, or damage to, any nuclear installation or facility in the other country .

Amending this paragraph could be done by adding “and certain critical infrastructure” after “any nuclear installation or facility.”

Next, “and certain critical infrastructure” could be added in paragraph 1(ii), which contains definitions, and could be specified to mean large dams.4 It is not worth covering every single weir, barrage, or water project in both countries, most of which would not meet the definition of critical infrastructure. Rather, the point is to focus on water withholdings of sufficient size for which failure would result in environmental and/or humanitarian catastrophe.

Here, the definition provided by the International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD) could be apt: any dam of a height greater than 15 meters and a withholding of more than 3 million cubic meters. According to the ICOLD registry, India has 5,102 such dams, while Pakistan has 163. Two of Pakistan’s dams are among the largest in the world by volume for flood protection, while two in Pakistan and one in India are among the tallest in the world. Given the disparity between the number of large dams in the two states, they might agree to declare an equal subset, for example the 50 or 75 most important dams in terms of potential consequences of a failure. Because these lists are already provided by each state to the ICOLD, there should be no sensitivity in sharing them bilaterally as part of the annual facility list exchange.5

To enact an information-sharing provision that would help both states avoid the potential negative outcomes of an attack on nuclear facilities or large dams, a simple clause could be added to the end of paragraph 1(i), as follows: “ … , and shall inform the other party in a timely manner regarding threats to such installations.”

The proposed changes also would focus both states on a broader shared interest in preventing attacks on critical infrastructures that could have regional effects. Such an agreement could also set a precedent for adding other types of critical facilities to non-attack and threat-information-sharing pledges.These additions could revitalize the agreement, giving it far greater meaning than its current symbolic impact – as long as they were implemented in good faith. They could change in important ways how each side plans to prosecute a war against the other by removing from the target list those facilities whose destruction could cause long-lasting, unjust, and disproportionate potential harm to civilian populations.

Nuclear facilities in both countries are relatively well protected (though not without issue or concern). Dams and other critical infrastructure are not as fortified, yet obviously are under threat. A 2012 U.S. Department of Homeland Security report, for example, describes two successful attacks on large dam facilities in India and two in Pakistan since 2004. All of these attacks involved militant groups; fortunately, none threatened the integrity of the dams. The report notes that attacks leading to dam “failure or disruption could result in deleterious results, including casualties, massive property damage, and other severe, long-term consequences, as well as significant impacts to other critical infrastructure sectors such as energy, transportation, and water.” In South Asia, it is likely that such attacks could also have significant impacts on agriculture, and cause substantial numbers of people to be internally displaced.

This revitalized agreement would also establish explicit acknowledgement of the growing threat from non-state actors to critical infrastructure. Implicitly, the existing agreement covers non-state threats, insofar as “indirect” threats by proxy actors might be “encouraged” by a state. It does not, however, deal with non-state threats that are not encouraged or directed by one of the states. Non-state actor threats to nuclear facilities motivated the establishment of the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism (in which both India and Pakistan participated) as well as the Nuclear Security Summits. Such threats are also a specific concern in South Asia, given the history of attacks in both countries by terrorist groups. Notwithstanding questions raised by New Delhi and Islamabad about the relationship of the other state to terrorist groups operating within or against each state, both states should have a strong desire to prevent terrorist attacks on nuclear facilities and other relevant critical infrastructure anywhere in the region.

The most direct way a state can help prevent terrorist attacks in another state, as well as to potentially mitigate perceptions of complicity if the attacks were to originate from its territory, is to share information about threats. There is a spotty record of such sharing in South Asia, but it is not without precedent. The Composite Dialogue between Pakistan and India inaugurated in 2006 a “joint anti-terrorism mechanism” for such a purpose, and media reports periodically indicate the sharing of intelligence on terror threats, mostly against civilian targets.

To be effective in mitigating potential threats, of course, information must be conveyed in time to prevent an attack. As such, a standing exchange arrangement – such as the annual trading of nuclear facility lists – does not meet the timeliness requirement. Instead, the governments would need to find another suitable means for communicating such information, for example in the channel between national security advisers. The point here is to find a balance between making such information-sharing routine, while retaining perspective on the significance of the threats being discussed.

Hurdles to Modernization

Refreshing the non-attack agreement in the manner suggested here addresses one potential source of nuclear threat in South Asia. In this regard, it would build on international nuclear security commitments already made by both states. It would also extend the scope of commitments to protect civil society from threats to other kinds of critical infrastructure. But augmentation in this fashion faces several serious hurdles. Here I will focus on two, but there are likely others.

Foremost among these hurdles, refreshing the non-attack pledges requires surmounting the “trust deficit” – not only with respect to the broader political climate, but also because of how it has been implemented to date. It verges on accepted knowledge among the analytic community that follows strategic issues in South Asia that the nuclear facility lists exchanged each year between the two states are incomplete. Given that the lists are kept secret, it is impossible to state with certainty whether all of the facilities that meet the agreed definition are included. But Indian and Pakistani analysts consistently argue that the lists are partial, with some suggesting that each side has left off one uranium enrichment facility.6 This issue surfaced anew in 2017, with charges by Pakistani officials that India is constructing a secret nuclear facility – the rumored plant at Challakere.7 Unless and until this plant actually contains nuclear material, India wouldn’t be obliged to include it in its annual list per the definition of the agreement. But this episode points to a more pertinent issue associated with the two sides’ security competition.

To improve the survivability of nuclear forces and therefore to strengthen deterrence, India and Pakistan have dispersed storage of nuclear warheads and delivery vehicles. Intelligence agencies in each country no doubt spend considerable effort monitoring suspected nuclear storage facilities in seeking to understand and forecast the nuclear operations of the other side. They would look for indicators that would warn of a change in the levels of readiness or alert, and also tracking information to feed into the strategic forces operations and plans process. For this reason, the nuclear-weapons establishments in each country undoubtedly expend considerable effort to hide such information.

Notably, nuclear-weapons-storage facilities are not explicitly covered by the non-attack agreement. Presumably few if any such facilities existed when the agreement was negotiated in 1988, so there would have been little reason to include them explicitly in the definitions section of the agreement. Today, in each country there are most likely a handful of weapons depots and related operational locations that store the fissile material cores of nuclear weapons, mostly located on or near military bases. An expansive reading of paragraph 1(ii) of the non-attack agreement, which defines “nuclear installation or facility,” would argue for the inclusion of weapons storage facilities under the definition: “installations with fresh or irradiated nuclear fuel and materials in any form and establishments storing significant quantities of radioactive materials.” But it is unimaginable that the two countries would report the locations of nuclear weapons storage facilities to each other, given the operational requirement to conceal them. Indeed, such facilities are likely to be on the high-priority target lists of each country’s military planners.

In theory, the non-attack agreement creates advantages that accrue to the state that is more transparent, to the extent that declared facilities would not be attacked. But neither state is willing to take that risk with regard to facilities of operational significance. As a matter of practice, it is also highly likely that in the context of an escalating conflict, nuclear-weapons-related facilities would be specifically targeted regardless of whether they were subject to the agreement.

The inherent trust deficit that results in the incomplete lists therefore limits the agreement’s potential utility as a measure to mitigate all threats to nuclear facilities, at least insofar as threat information might only be shared about facilities on the list. Indeed, a state might possess information about a threat specific to a weapons-storage facility not on the list, but might not want to reveal its knowledge to the other state. At the same time, providing vague or generic threat information not specific to a facility limits its usefulness. Given contemporary security relations in South Asia, there may be little to be done to correct for this deficiency. Perhaps in the future India and Pakistan might develop sufficient trust to share complete nuclear facility lists – for example, if they were to engage in an arms control process.

Exchanging information on non-state actor threats to covered facilities also poses some specific challenges. First, there is the issue of sources and methods, which always hovers around intelligence-sharing. Intelligence agencies are biased toward collecting information, not disseminating it to other agencies in the same state, let alone to foreign adversaries. If the information involved focused on groups operating within the other state (i.e., Pakistan’s sharing information on the Indian Mujahidin or India’s sharing information on the Pakistani Taliban), questions about sources and methods would necessarily come into play. It seems more plausible from a sources and methods point of view to share threat intelligence on groups that might cross borders. It is not clear from the public record how these questions have been handled in past instances, but clearly a calculus exists to support such sharing.

It is also worth raising the very real issues associated with state support for proxy groups that carry out attacks against the other state. There is a lengthy record of information and scholarship about Pakistan’s support for such groups (mainly Laskhar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad) and complicity in prior attacks. There is less specific public information and analysis about parallel Indian support for groups carrying out attacks in Pakistan, namely the Pakistani Taliban and Baloch separatists, although Pakistanis certainly believe such Indian support to be a fact. If either state does have control of such groups, then presumably they could prevent attacks on facilities covered by the agreement. If affirmative control over these groups does not exist, however, then the question of information-sharing becomes apt, at least as a means of mitigating blame. But that doesn’t obviate the question of how the party receiving the information might treat it. Indian officials, for example, might well discount information from Pakistan on the presumption that the information could not be trusted or was offered as an attempt to avoid blame for what was in actuality a sponsored attack.

Avoiding Civilian Catastrophe

Notwithstanding these hurdles, both states could well decide that the risks and challenges are outweighed by the potential benefits of modernizing the non-attack agreement.

Today, India and Pakistan both expend significant diplomatic effort in search of international legitimacy as responsible possessors of nuclear weapons. They both seek entry into the exclusive Nuclear Suppliers Group. They participated in the Nuclear Security Summit process. And they are engaged in nuclear-reactor construction projects involving foreign suppliers. As such, each state has a strong interest in preventing nuclear incidents at its own – and, arguably, at the other’s – nuclear facilities.

The potential environmental and humanitarian consequences of an attack on a nuclear facility or dam could range from negligible to severe. Existing modeling of radiation effects from an exchange of nuclear weapons in South Asia provides some sense of the potential magnitude of such an event, albeit with a very different set of assumptions. But an accident at a nuclear reactor could also result in substantially harmful levels of radiation released into the atmosphere. Depending on the location of the event and prevailing winds, such a release could have far-reaching effects on population centers and agriculture belts in both countries. Given the population density in South Asia and the governance challenge of managing the consequences of a radiation release, the potential that a nuclear accident could result in humanitarian catastrophe is significant. An attack on a large dam also could produce severe consequences, albeit without radiation effects.

An attack on a nuclear facility or a large dam could also precipitate a major security crisis. There is a propensity for officials and politicians in both India and Pakistan to blame militant groups based in or supported by the other state for any attacks that occur on its territory.8 It is thus reasonable to predict that an attack on a Pakistani nuclear facility or other critical infrastructure carried out by the Pakistani Taliban or Baloch militants would be blamed on purported Indian support for such groups, just as it would be reasonable to expect that responsibility for an attack on Indian critical infrastructure, attributed to Lashkar-e-Taiba or Jaish-e-Muhammad, would be blamed on Pakistan. Whether or not such an attack was actually supported or directed by the opposing state, it is reasonable to expect that the victim might conclude that it was, either to shift blame or because of analytic bias. 9

The heated rhetoric and demands for retribution that would follow such an attack – some politicians and hawkish news commentators would no doubt term it an act of war – could instantly plunge both states into a political-military crisis with unknown prospects for escalation.

In addition, as was seen following the accident at the Fukushima-Daichi nuclear power station in Japan, an incident at a nuclear facility in either India or Pakistan could seriously disrupt and potentially derail nuclear energy production in both states. The blow to the international and domestic prestige accorded nuclear power would be severe, causing foreign technology suppliers and their financiers to question whether the potential liability and reputational damage was worth the risk of investment in projects in the region. (This could especially impact China, since Beijing is betting that its nuclear-reactor construction projects in Pakistan will help it develop a larger export market.) Such an event would also cause damage to domestic support for nuclear power, especially given the propensity for local opposition, such as that surrounding reactor projects in Karachi and Kundankulam. The diminution or death of nuclear energy production also would have tertiary effects on economic development and climate-change-mitigation plans, with both states inevitably having to invest greater resources in more carbon-intensive sources of energy, with all the attendant air pollution implications.

Officials in both countries presumably understand these and other potential consequences of a nuclear incident at one of their facilities, which should motivate their nuclear security practices. Modernizing the agreement would lend credence to the rhetorical support both countries have placed on strengthening nuclear security. For example, both heads of government attended the Nuclear Security Summits convened biennially from 2010 to 2016; each government constructed a “center of excellence” to provide training on nuclear security and related topics; and each engages the International Atomic Energy Agency in a range of nuclear security training and review activities.

However, in the course of strengthening nuclear security practices, India and Pakistan have eschewed formal bilateral cooperation or exchanges. Officials from both countries dismiss proposals for such cooperation as too sensitive or politically inexpedient. Ironically, both often raise concerns about the nuclear security practices of the other to question the “responsible nuclear state” bona fides for purposes of international point-scoring. Understandably and legitimately, given long-standing security tensions in South Asia, each side has concerns that bilateral nuclear security cooperation might inadvertently reveal vulnerabilities. The lack of trust preventing such cooperation is unlikely to be redressed any time soon. However, focusing on mitigating threats rather than sharing nuclear security practices would avoid this sensitivity.

Conclusion

Avoiding nuclear war is the paramount responsibility of states with nuclear weapons, followed closely by avoiding other nuclear incidents that could lead to war or other human or environmental catastrophe. Nuclear weapons are now a defining feature of the strategic landscape in South Asia, and will be for the foreseeable future. It is therefore incumbent on India and Pakistan to take all necessary steps, both in their national practices and in their bilateral relations, to mitigate threats to nuclear facilities. This proposal – to bring a confidence-building measure negotiated before the advent of nuclear weapons into the post-nuclear-weapons context – would be a useful step toward meeting this responsibility.

Inherent in this responsibility is a broader principle to mitigate serious threats to civilian populations. Given the shared geography in South Asia, this is not merely an “other-regarding” principle, but recognizes that civilian catastrophes could easily transcend political boundaries. Expanding the scope of the agreement to cover not just nuclear facilities but other types of infrastructure, and also to recognize non-state threats to that infrastructure, would similarly commit India and Pakistan to useful principles of bilateral conduct that are good for the region as a whole.

One could also hope – recognizing that hope is not a good basis for policy – that modernizing the non-attack agreement as suggested here might support habits that would spill over into other arenas. Narrow sharing of intelligence on threats to covered facilities could yield a more fruitful anti-terrorism dialogue. It could also provoke broader discussion on best practices for protection of critical infrastructure, and perhaps even lead to cooperation along these lines. These would be small but useful steps pointing the way toward an off ramp from intensified nuclear competition. Of course, such steps in isolation are unlikely to end the India-Pakistan security competition, or even to prevent future terror attacks. But the intrinsic value of cooperation to mitigate threats to critical infrastructure – and civil society more broadly – makes them worth pursuing all the same.

Editor’s Note: This essay is part of a new Stimson Center book,Off Ramps from Confrontation in Southern Asia, and has been republished with permission. The book features pragmatic, novel approaches from rising talent and veteran analysts to reduce tensions resulting out of nuclear competition among India, Pakistan, and China. The full book is available for download here.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: India Water Portal via Flickr

Image 2: U.S. Embassy Pakistan, Tarbela Dam via Flickr

- See discussion in P. R. Chari, Pervaiz Iqbal Cheema, and Stephen P. Cohen, Four Crises and a Peace Process(Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2007), 24-27.

- R. Rajagopalan and A. Mishra, Nuclear South Asia: Key Words and Concepts (Routledge, 2014), 200-201.

- Notably, notwithstanding implementation of the agreement and a decade of annual list exchanges, some in Pakistan were concerned that India might conduct a preemptive attack following Delhi’s nuclear tests in early May 1998. See Maleeha Lodhi, “Dealing with South Asia’s Nuclear and Security Issues,” Defence Journal, January 1999, http://www.defencejournal.com/jan99/nuc-sec-issues.htm.

- The benefit of a broad category such as “certain critical infrastructure” is that it easily could be amended later to include other types of facilities.

- How large dams located in disputed territory in Kashmir might be handled under the agreement is an important issue. Suffice to say, the two sides could stipulate that the listing of such dams would have no bearing on questions of how the dispute might eventually be resolved. But this may be easier said than done.

- For instance, Amitabh Matoo, “Military and Nuclear CBMs in South Asia: Problems and Prospects,” in The Challenge of Confidence Building Measures in South Asia, ed. Moonis Ahmar (New Delhi: Har Anand Publications, 2001), 208; and W. P. S. Sidhu, “India’s Security and Nuclear Risk-Reduction Measures,” in Nuclear Risk-Reduction Measures in Southern Asia, Stimson Center, Report No. 26, November 1998, 40.

- Devirupa Mitra, “Six Weeks After Exchanging N-Lists, Pakistan and India Trade Barbs over ‘Secret’ Nuclear City,” The Wire, February 9, 2017.

- This is an observation of the national discourse in India and Pakistan, not an analytic judgment on the veracity of those claims and the potential equivalence implied.

- If the attack involved a facility storing nuclear weapons and/or if the states were already in a period of heightened tension, this would be even more the case, for it could be (mis)interpreted as a preemptive attack.