This summer marks a quarter century since the Kargil conflict, and a lot has changed between Pakistan and India in the intervening years. Several crises have ensued. Islamabad and New Delhi have come close to potential war more than once. And both countries have modernized their nuclear arsenals, adjusting doctrines as well as force postures to adapt to a changed security landscape and threat perceptions. While a future crisis may not look like Kargil and could have a trigger point beyond Kashmir, the recurrence of a military crisis in South Asia is not an ‘if’ but a ‘when.’

The evolving nature of warfare reveals the limitations of solely relying on nuclear weapons for deterrence. Weapon systems such as Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAVs) have the potential to cause significant destruction without nudging the nuclear threshold. Cyber warfare can introduce new escalation dynamics in an India-Pakistan military crisis. Additionally, the significant disparity in defense budgets between India and Pakistan further exacerbates Islamabad’s challenges and has potentially shifted the deterrence balance.

As Pakistan attempts to address these gaps, its internal civil-military discord and lack of public support undermine the effectiveness of its deterrence. Unless there is an integrated approach combining military preparedness with political stability, economic resilience, and public support, Pakistan’s ability to navigate future crises will remain limited and crisis stability may be threatened.

The evolving nature of warfare reveals the limitations of solely relying on nuclear weapons for deterrence. […] Cyber warfare can introduce new escalation dynamics in an India-Pakistan military crisis.

Nuclear Deterrence and the Changing Nature of War

Deterring external aggression was Pakistan’s main motivation behind acquiring nuclear weapons, and the Kargil war was a premature attempt at testing this protection. At the time, Pakistani decisionmakers argued that deterrence was not “operationalized,” meaning that Pakistan did not have usable nuclear weapons.[1] Since then, Pakistan is estimated to have produced up to 170 nuclear weapons, including strategic and tactical nuclear weapons and missiles ranging from 60 to 2,750 km. Its nuclear posture has evolved from minimum credible deterrence to credible minimum deterrence, and now full spectrum deterrence (FSD) and Quid Pro Quo Plus (QPQP+). In the absence of a declaratory nuclear doctrine, Pakistan’s strategic rhetoric signals to India that the country is ready to counter all kinds of external aggression through its nuclear capabilities.

The missing piece in Pakistan’s nuclear posture is that some threats to external aggression cannot be deterred by nuclear weapons. Since the Kargil War, emerging technologies such as cyber, UCAVs, and military integration of artificial intelligence (AI) have driven significant changes in military planning. Nuclear weapons are a blunt instrument in the face of more nuanced and varied technological threats. They do not provide the flexible options needed to address the range of potential attacks possible in today’s world.

UCAVs and cyberattacks can cause significant damage to command-and-control facilities and other critical infrastructure without crossing the nuclear threshold or even resembling a conventional military action. This makes it difficult to determine when a nuclear response might be warranted. The threat of nuclear retaliation may not be credible for lower-level technological aggressions, thus creating gaps in Pakistan’s deterrence. Additionally, threatening nuclear retaliation against these technologies could lead to rapid escalation, which can potentially turn a limited conflict into a full-scale nuclear exchange.

Conventional Deterrence

Kargil was a conventional war under a nuclear overhang. But a future military crisis would be as much a competition of technologies as it would be of skill and strategy. A combination of advanced air defense; state-of-the-art weapons systems on land, air, and sea (Arjun Mark 1A and II main battle tanks, K9 Vajra self-propelled howitzer, Rafale multirole fighters, INS Vikrant aircraft carrier, and Scorpene-class submarines); and precision-guided munitions (such as Israeli-developed SPICE bombs) have considerably enhanced India’s conventional deterrence and operational readiness. Platforms such as C-17 Globemaster III transport aircraft and Apache AH-64E attack helicopters act as force multipliers and would allow for rapid troop and material deployment. These systems enhance India’s ability to sustain prolonged operations and respond swiftly to emerging threats across diverse terrains. With these capabilities, India can potentially conduct targeted operations inside Pakistan without escalating to full-scale mobilization of its forces.

On the other hand, Pakistan has also acquired advanced conventional weapon systems to increase the credibility of its deterrence. The acquisition of the indigenously-produced JF-17 Thunder fighter jets, upgraded Agosta-90B class submarines with air-independent propulsion (AIP), Chinese-built Type 054A frigates, Fatah-II guided rocket system, and early warning systems such as Erieye Radar and Saab 2000 aircraft is likely to have made military action less attractive for India. Pakistan’s ability to shoot down an Indian fighter aircraft and capture the pilot during the Pulwama-Balakot crisis in 2019 demonstrated the centrality and capabilities of the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) in the country’s deterrence strategy. The acquisition of a diverse array of conventional weapon systems provides Pakistani decisionmakers with a wider range of response options and allows for more nuanced and proportionate deterrence strategies in a post-Kargil world.

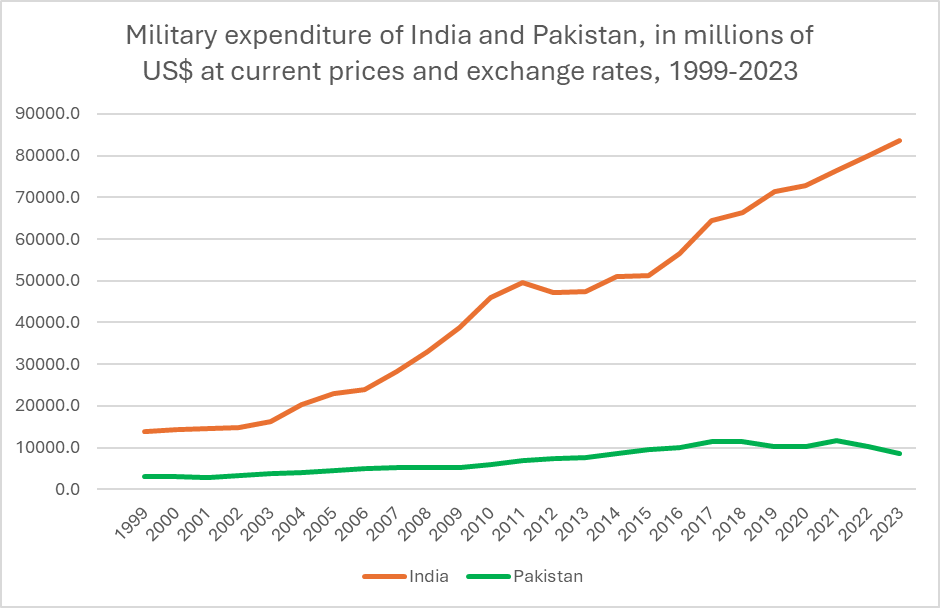

However, despite Pakistan’s advancements, the widening gap in defense spending poses imminent challenges to Pakistan’s military parity with India (see figure below, calculated from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database). In 2023, India’s military expenditure stood at USD$83.6 billion, nearly ten times higher than Pakistan’s military expenditure of USD$8.5 billion. This gap in defense budgets has implications for Pakistan’s conventional and nuclear deterrence against India. Higher spending allows India to have a qualitative edge in conventional weapon systems. Thus, this conventional imbalance potentially shifts the deterrence dynamics in favor of India.

Pakistan can still maintain deterrence against large-scale invasions or existential threats through its nuclear capabilities. But conflict scenarios in which Pakistan aims to prevent limited Indian operations such as air strikes or low-level armed conflict can disturb strategic stability.

To compensate for the growing conventional gap with India, Pakistan will likely increase its focus on improving its asymmetric capabilities. One way of doing so would be the acquisition of UCAVs. The Russia-Ukraine armed conflict has shown that these small and inexpensive drones equipped with surveillance or even weapon systems can provide states with enhanced capabilities for reconnaissance, targeting, and strike missions. Their ability to conduct precision strikes with reduced risk to operators has altered the calculus of military engagement. In South Asia, the asymmetric nature of drone warfare would give Pakistan more options against technologically advanced India.

Pakistan’s indigenous drone program and the recently inducted Turkish-origin Bayraktar TB2 and AKINCI drones give it an early-mover advantage over India in the short-term as Pakistan has already deployed these drones while India is facing delays in both acquisition and operational integration. However, the induction of the 31 MQ-9B drones recently purchased from the United States would likely offset Pakistan’s advantage. In that case, the employment of innovative tactics may lead to unpredictable outcomes. Since a nuclear response is unlikely, Pakistan could employ its drones to conduct electronic warfare by jamming, spoofing, or disabling India’s drone and communication systems. Investment in and the adoption of asymmetric and unconventional drone tactics (e.g. psychological operations or diversionary tactics) could leverage drones in innovative ways to disrupt and deter India’s forces without escalating to full-scale conflict.

Such scenarios would at minimum raise the potential costs of conducting drone strikes inside Pakistan, thereby improving conventional deterrence in a future India-Pakistan crisis scenario. However, Pakistan has yet to exhibit these operational changes through its doctrine and military exercises. It does not have huge number of drones at present to conduct swarm operations. The cost of strengthened deterrence may lie in increased defense spending and focus on improving asymmetric capabilities.

Cyber Domain and Deterrence

Threats in the cyber domain introduce a new dimension to crisis stability by disrupting traditional escalation ladders and crisis management protocols. Cyberattacks targeting critical infrastructure such as power grids, telecommunications networks, and financial systems can have far-reaching consequences for regional stability. The frequency of state-sponsored cyberattacks on Indian and Pakistani entities increased after the Pulwama-Balakot crisis. This trend indicates a growing risk of cyber operations increasing tensions even after apparent de-escalation of conventional conflicts. A cyberattack on critical infrastructure could be interpreted as a prelude to a larger offensive and can prompt a disproportionate response. Cyber operations can complicate the understanding of signals and thresholds and make it difficult to de-escalate a crisis.

One of the key challenges in cyberspace is the difficulty in attributing cyberattacks to specific actors with certainty. This ambiguity can lead to misperceptions, uncertainty, and escalation spirals, as Pakistan and India would try to decipher the intentions behind cyber incidents and respond accordingly. For example, if the timing of the cyberattacks on the Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant (attributed to North Korean hackers) or the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) had coincided with an active India-Pakistan military crisis, it could have potentially escalated the crisis, despite unverified attribution. This also implies that cyberattacks occurring during periods of heightened tensions are more likely to be viewed as deliberate provocations even if they are unrelated to the ongoing crisis.

A two-pronged approach can strengthen Pakistan’s deterrence in the cyber domain and avoid inadvertent crisis escalation. One, Pakistan could invest in advanced cybersecurity technologies and practices to protect critical infrastructure from cyberattacks. This would bolster its capabilities to monitor, detect, and attribute cyber threats in real-time. The formulation of clear national cyber policies that define the response protocols to cyber incidents would improve the response strategies and signal the resolve to retaliate against the adversaries. Two, establishing secure communication channels with India to quickly address and clarify cyber incidents during crises would prevent inadvertent escalation due to misattribution or miscommunication. By enhancing its cybersecurity measures and establishing bilateral communication with India on cyber incidents, Pakistan can better defend against cyberattacks, improve crisis stability by reducing the risk of dangerous escalation, and foster a relatively more predictable crisis environment.

Political-Economic Stability and the Civil-Military Divide

While the measures suggested above can enhance Pakistan’s crisis preparedness, they may in some ways clash with domestic priorities. Pakistan is facing a period of high political and economic instability. The trust deficit between the masses and elite, resentment among Pakistanis about the electoral process, opposition to the measures introduced by the government in line with its loan agreements, worsening economic stability, and increasing cost of living are all factors that would have an impact on Pakistan’s preparation for and response to a future crisis. If Pakistan increases its defense budget to enhance its conventional deterrence and allocate precious resources to modernize its nuclear arsenal, there could be widespread opposition to these policies. The guns vs. butter debate may be difficult to manage because of the ongoing political and economic challenges.

A second concern centers around the divide between the people and the military. The morale of the armed forces and the ability to invest in their defense preparedness are dependent on public support. This backing is indispensable for a successful response to a military crisis. However, aside from the biggest political party in Pakistan, all other political parties are in the government and enjoy military backing. The current weak coalition government lacks domestic legitimacy as it came into power through what wide sections of the Pakistani populace perceive as a stolen mandate. To address this civil-military divide and ensure public support for policies enacted in a crisis, Pakistan’s military establishment would have to operate within its constitutional mandate and cease its interference in political and governance issues. Moreover, fissures in domestic politics and lack of public support signal weaknesses that can be exploited, undermining the deterrence value of even the most modernized military. Propaganda, information warfare, and psychological warfare can also thrive in a highly polarized environment – making Pakistan an easy target.

Instead of overreliance on its nuclear deterrent, Pakistan should focus on bolstering its deterrence against conventional and cyber threats. In this regard, it needs to consider cost-effective options, e.g. indigenous drone program, early warning systems, and enhancing cyber offense and defense capabilities. It should contemplate adjusting its military warfighting doctrine to include innovative employment of emerging technologies and weapon systems that might give Pakistan a strategic advantage in the battlefield and therefore strengthen deterrence. Lastly, modernizing the military without addressing governance and societal issues would be an incomplete approach to national security. The credibility of deterrence is not only about military capability but also about the nation’s resolve and coherence in its strategy.

***

Image 1: Amit Rawat via Flickr.

Image 2: Bayhaluk via Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Pervez Musharraf, In the Line of Fire: A Memoir (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 97–98.