For the 23 years since their 1998 nuclear tests, India and Pakistan have not used nuclear weapons; however, they exchanged several nuclear threats in all military crises, including the limited Kargil conflict in 1999. In South Asia, nuclear restraint1 is more fragile than a nuclear taboo2 because taboos have reprehensible costs and consequences attached to them. In the absence of political dialogue and ongoing tensions on the border, the political leadership on both sides is in a difficult spot to maintain restraint in future escalation. Limited nuclear use in South Asia would cause massive collateral damage, casualties, famine, destruction, and economic turmoil and leave behind years of the diseases for generations. Therefore, it is necessary to question the fragility of both nuclear restraint and the nuclear taboo in South Asia.

This article reviews the debate of nuclear restraint/taboo in South Asia in response to a recent thought-provoking policy paper by Nina Tannenwald. I argue that nuclear nonuse in South Asia is a temporary nuclear restraint based on the military-utility principle. Daryl G. Press, Scott D. Sagan, and Benjamin Valentino articulate the concept of military-utility principle as the “logic of consequences” where nuclear nonuse is privy to the objectives and the immediate efficacy of the weapon, strategy, or tactic. I further argue if nuclear restraint (currently at the decision-making level in India and Pakistan) can transform into a nuclear taboo (both at state and societal levels), then there is a high probability that nuclear weapon nonuse will continue in South Asia. Nuclear restraint can strengthen if leadership takes measures to constrain the employment of nuclear forces, diversify options, and make efforts for risk reduction and arms control measures. However, a weak nuclear taboo makes restraint more vulnerable because leaders may risk escalation in an atmosphere of nuclear nationalism and threat rhetoric. Considering that both countries are constantly upgrading their strategic forces and counterforce targeting capabilities, the recurrence of military crises pushes nuclear restraint to test and challenge the notion of taboo in South Asia.

A weak nuclear taboo makes restraint more vulnerable because leaders may risk escalation in an atmosphere of nuclear nationalism and threat rhetoric. Considering that both countries are constantly upgrading their strategic forces and counterforce targeting capabilities, the recurrence of military crises pushes nuclear restraint to test and challenge the notion of taboo in South Asia.

Nuclear Taboo Discourse in South Asia

Nina Tannenwald – the leading expert on the nuclear taboo – in her latest article entitled “23 Years of Nonuse: Does the Nuclear Taboo Constrain India and Pakistan?”, questions if the practice of nuclear nonuse in South Asia “[carries] normative ‘weight.'” Tannenwald examines how the evolution of nuclear taboo in the United States and the Soviet Union came about by strengthening arms control and supporting global anti-nuclear movements that reinforced mutual deterrence. Her findings regarding South Asia are different because, as she writes, the “resurgent nationalist and religious sentiment in both countries fan the flames of conflict escalation.” According to her, as the taboo strengthens over time, it is “inherently less powerful in the newer nuclear weapons states.” In South Asia, Tannenwald writes that “although a discourse of the taboo exists, the taboo itself is fragile.”

I broadly agree with Tannenwald’s findings on the fragility of nuclear taboo, which take into account force postures and doctrines in India and Pakistan, as well as statements made by scholars or leadership “indirectly [invoking] the taboo.” However, looking to leadership discourses as evidence is debatable because: First, such discourses are few compared to the nuclear threats communicated between two sides. Second, the reality of political rhetoric makes it hard to prove the “taboo” argument. While some Pakistani academics or politicians attest to the existence of the taboo, most of the scholarly debate supports defense production and purchases as well as offensive posturing. Scholars and practitioners keep moving the markers of credible deterrence in favor of offensive force postures that contradict the restraint/taboo statements. For instance, as Tannenwald notes, Zafar Jaspal has written that “[Pakistan’s] ruling elite believes in the nuclear taboo.” He also suggests, however, that “Pakistan could launch a nuclear attack using deep penetration strike aircraft” or “employ its supersonic cruise missiles to evade enemy’s radar…while striking the target.” It is also hard to confirm the status of taboo when Maj. General Asif Ghafoor’s statement that “no sane country…would talk about using it” but has also said that “Pakistan would launch ten if India launched one surgical strike.” This statement explains Pakistan’s “Quid- Pro-Quo Plus” strategy and raises questions on how much is this “Plus”? Is it “meeting India’s use of force and adding a little more,” as pointed out by Tannenwald, or is it implying ambiguous response options with the possibility of limited nuclear use to thwart Indian aggression? Pakistan’s nuclear doctrine and force posture negate the notion of “nuclear taboo” and weaken nuclear restraint. The full spectrum doctrine aims to increase ambiguity, fear, and risk of nuclear use to dissuade India from crossing the border. Lt. General Khalid Kidwai mentioned battlefield nukes would make India think twice of war, and “if war is not deterred, then obviously some kind of mad doctrine will come into play.”

Third, it is unclear how and why such discourses would be instrumental “to position Pakistan as the restrained, responsible state,” as suggested in Tannenwald’s policy paper. The Pakistan establishment not only contested the standards and vocabularies of “normal” and “responsible” used by western scholars but also mentioned that the “selective application of the nonproliferation regime” ignored Pakistan’s efforts to “observe nonproliferation norms in their letter and spirit.” The important question is if Pakistan is interested in projecting a “restrained” nuclear weapons state through nuclear discourse? Pakistan’s deterrence logic rests on its “resolve to use nuclear weapons first.” Lt. Gen. Kidwai recently stated: “it is the Full Spectrum Deterrence capability of Pakistan that brings the international community rushing into South Asia to prevent a wider conflagration.”

If crisis escalation continues with India’s border and/or Line of Control (LoC) transgressions, Pakistan may very well be the first to use nuclear weapons in the region.

Although nuclear threats may have gone along with India and Pakistan exercising nuclear restraint in South Asia, the real challenge is if India keeps calling Pakistan’s restraint a “nuclear bluff” then Pakistan may call the Indian bluff and violate “taboo” with limited nuclear detonation in the desert or at sea. As I mentioned in a previous article, “Nuclear Ethics? Why Pakistan Has Not Used Nuclear Weapons…Yet”, it would be ethical, logical, and legally justifiable for Pakistan nuclear-use in self-defense even though it would break the norm of nuclear taboo. The limited use of nuclear weapons would show resolve and re-establish comprehensive deterrence in the region. If crisis escalation continues with India’s border and/or Line of Control (LoC) transgressions, Pakistan may very well be the first to use nuclear weapons in the region.

Pulwama – A New Normal?

The Pulwama crisis is not a hopeful case for nuclear restraint, taboo, or deterrence stability. Proponents of nuclear deterrence forget that each India-Pakistan crisis is gradually scaling up the escalation trends. In the 2002 standoff, both countries chose not to cross the LoC or international border. In 2008, political and diplomatic faceoffs ended the composite dialogue and efforts for Confidence-Building Measures (CBMs). In the 2016 Uri attacks, India allegedly conducted surgical strikes against terrorist launch pads across the LoC. In the 2019 Pulwama crisis, Indian warplanes crossed the LoC for strikes in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, and later claimed the strike had “[killed] 300 terrorists.” High-resolution satellite imagery refuted the claims, noting the religious school India “claimed its warplanes had hit,” appeared “to be still standing.” The crisis escalated further with Prime Minister Modi’s threat to use a conventional missile against Pakistan if Pakistan did not release the Indian Air Force pilot captured after an aerial dogfight between the Pakistani and Indian air force.

The Article 370 withdrawal also reinforces Pakistan’s security concerns and have brought Pakistan’s civilian and military leadership to greater consensus on threat perceptions. Crises like Pulwama burned the bridge that some civil society members were pleading to restore peace and strengthen nuclear nonuse norms.

What makes Pulwama escalation different from previous crises is that the Pakistan military was prepared but undeterred to respond in kind to its conventionally superior adversary. It challenged India’s “hit-and-run” war plans and established a “new normal” in Indo-Pakistan crisis escalation. The future South Asian crisis may be riskier for the following reasons: First, in the event of a future crisis, India may seek to avenge the downing of a MiG-21 for “perception victory.” Indian analysts and media shared dissatisfaction and called out Indian leadership for the lack of an “unambiguous victory.” The future crisis could be dangerous if the Indian military targets Pakistan’s forward base instead of a “madrassah.” Former Indian Air Force chief BS Dhanoa claimed after Balakot that “[Indian military] posture was very offensive… we were in a position to wipe out [Pakistan’s] forward brigades.” Second, is the absence of third-party mediation (from the United States) to enforce risk-reduction and nuclear restraint in South Asia. Unlike previous crises, during the Pulwama crisis the international community did not condemn India’s cross-border escalation. In fact, United States’ former national security advisor, John Bolton, “supported India’s right to self-defense.” Third, Pakistan has less direct stake in maintaining a strong relationship with the United States, which has previously pressured Pakistan to maintain the policy of nuclear restraint. The anticipated complete withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan and the suspensions of economic and military aid leave a diplomatic vacuum to oversee deterrence stability as a “neutral” third party. China is less likely to fill the role because of its changing conflict dynamics with India.

Finally, India’s abrogation of Article 370 and 35A brings Jammu and Kashmir under the central government’s control as a Union Territory. This policy questions the role of the LoC. While ceasefire violations have been increasing on the LoC, these violations have de-escalated before any conflict could expand to the international border. Will this political measure impact the Indian military’s perception of “attack” and subsequent’ response options’? The latest report of Strategic Futures Group, a National Intelligence Council think tank, warns that “India and Pakistan may stumble into a large-scale war neither side wants, especially following a terrorist attack that the Indian Government judges to be significant.” The Article 370 withdrawal also reinforces Pakistan’s security concerns and have brought Pakistan’s civilian and military leadership to greater consensus on threat perceptions. Crises like Pulwama burned the bridge that some civil society members were pleading to restore peace and strengthen nuclear nonuse norms. Therefore, Nina Tannenwald’s finding that the Balakot crisis moved India farther but perhaps moved Pakistan closer to a nuclear taboo – as evidence by statements from leaders and scholars and public opinion surveys in the wake of the crisis – may be overly optimistic. Instead, both countries are moving away from the nuclear taboo.

Overall, however, I strongly agree with Tannenwald’s conclusion that taboo is fragile in Pakistan because leaders see “nuclear weapons as their ultimate defense.” Further, the United States’ key role in the past in “preserving the norm of nonuse in South Asia by mediating crises and encouraging restraint” may not be the reality in the foreseeable future. As Tannenwald recommends, both India and Pakistan should restore dialogue and work to establish an arms-control relationship, while stepping back from force postures that cause fear of preemptive or decapitating strikes.

What Can be Done?

The debate on the nuclear taboo in South Asia could benefit from examining U.S.-Cold War escalation trends and improving leaderships’ ability to invest in deterrence stability. Nina Tannenwald’s previous book, The Nuclear Taboo, could inform the evolutionary stages of strengthening the nuclear taboo in India and Pakistan. With numerous strong CBM and risk reduction proposals, Indian and Pakistani policymakers’ can strengthen the policy of nuclear restraint. To begin with small steps, I recommend the following measures to improve the policy of nuclear restraint, which in the future could transform into a nuclear taboo. First, leaders need to make substantive efforts to establish trust at the political, bureaucratic, and societal levels. Both sides can benefit from the DGMOs hotline or direct telephone exchange between the two prime ministers to avert crisis escalation. Amid the global challenge of COVID-19, Pakistan offered “to provide relief support to India,” currently facing the highest surge of cases/deaths every day. India has not responded yet, and if India foregoes, South Asia will lose another opportunity where two countries could start a new chapter of their relationship.

The nationalist propaganda and warmongering 24/7 coverage of the crisis on electronic and social media is fueling public sentiments with incomplete information. Such jingoistic journalism is eroding prospects of peace in the region.

Second, political leaderships need to stop capitalizing on pro-war and anti-peace rhetoric to secure election victory. Instead of bringing the war to their nations in a nuclear environment, leaders should promise economic prosperity and work on the principle of “your welfare is my welfare.” Economic interdependence and mutual trade would increase cooperation. After the 2008 attacks, local investors faced heavy losses from the suspension of bilateral relations. Businesses and industrialists support election campaigns; they will keep elected leaders’ pro-war rhetoric under control when monetary stakes are involved. Third, the nationalist propaganda and warmongering 24/7 coverage of the crisis on electronic and social media is fueling public sentiments with incomplete information. Such jingoistic journalism is eroding prospects of peace in the region.

Fourth, both countries should develop a robust intelligence-sharing framework not to trigger any terror incident into a military crisis. This January, senior intelligence officers from India and Pakistan reportedly met in Dubai to “[normalize] ties over the next several months.” Skeptics, however, are less hopeful of ISI and RAW meetings to yield fruitful results. Fifth, the religious and cultural norms of South Asian society could facilitate promoting nuclear taboo. Southern Asia is proud of its cultural heritage and religious values. Therefore, the masses need to question their leadership in nuclear use options that guarantee destruction/annihilation. Nina Tannenwald rightly noted that “citizens and journalists should pose questions about the taboo to their national leaders.” The region holds significance to Sufi Islam, where worshippers revere shrines, Hindu temples, and Sikh Gurdwaras, sacred to destruction. In 2018, both sides opened Dera Baba Nanak-Kartarpur Corridor (also known as the Peace Corridor) to facilitate Sikh pilgrims on visa-free travel to visit Gurdwara in Pakistan. Such policy measures are essential to connect people on both sides of the border, shape peace perceptions, facilitate travel, and promote the tourism industry. Finally, a comprehensive study of limited nuclear use in Southern Asia would be crucial to examine the taboo violation’s social, political, and economic costs. The study group can evaluate the findings and strategize civil-defense campaigns to educate people on the devastating impacts of any nuclear use.

Editor’s Note: This piece is part of a collection of SAV articles reviewing Nina Tannenwald’s Stimson Center Policy Paper: “23 Years of Nonuse: Does the Nuclear Taboo Constrain India and Pakistan?” Be sure to read the full series and watch the webinar discussion on the role of the nuclear taboo in India and Pakistan, featuring Dr. Tannenwald, Dr. Manpreet Sethi, and Dr. Sannia Abdullah.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

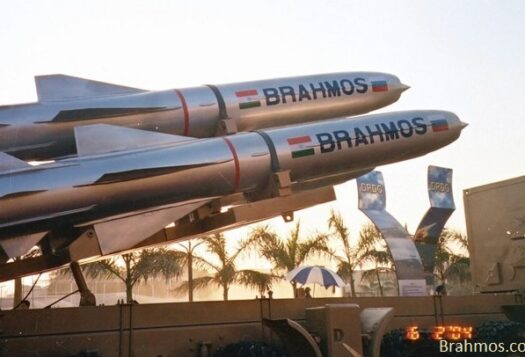

Image 1: via PxHere

Image 2: Aamir Quereshi/AFP via Getty Images

- Restraint is a “condition that limits and control someone’s behavior who is capable of doing it but choose not to do because it is necessary and sensible not to do it.”

- Taboo, however, is a “cultural or religious custom that does not allow people” to act in a certain way because it is offensive.