In 2018, Sufian Ullah analyzed the role of expanding counterforce technologies in South Asia in light of Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press’s International Security journal article, “The New Era of Counterforce: Technological Change and the Future of Nuclear Deterrence.” His words, republished below, remain a timely assessment of emerging challenges to stability on the subcontinent.

***

Instead of reducing reliance on nuclear capability as a step towards disarmament, nuclear weapons states have been steadily modernizing their nuclear forces. Offensive nuclear postures, along with ambiguous nuclear doctrines, continue to threaten international security. In the early years after the advent of nuclear weapons, cities were the primary targets for inaccurate ballistic missiles and strategic bombers. However, technological innovations have introduced the possibility of attacking an adversary’s nuclear forces and incorporating counterforce targeting into national military strategies. One case in point is Robert McNamara’s famous “No Cities” 1962 speech, which proposed that United States would only target adversary’s military installations. As nuclear attacking capabilities become more sophisticated, the dangers of the possible use of nuclear weapons continue to grow.

In context of this trend, Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press argue in their International Security journal article, “The New Era of Counterforce: Technological Change and the Future of Nuclear Deterrence,” that as counterforce technologies improve, the survivability of arsenals becomes increasingly uncertain, thus affecting deterrence relationships between nuclear adversaries. Although the article was written in the context of U.S. counterforce capabilities, this review can be applied to how growing counterforce weapons in South Asia affect deterrence stability between Pakistan and India.

Rethinking Nuclear Deterrence in a New Era

Lieber and Press assert that rapid changes in technology are eroding the foundations of nuclear deterrence. The improved accuracy of delivery systems and advanced sensing technologies are reducing confidence in the nuclear survivability and have several implications. First, this calls for the development of advanced retaliatory forces. Second, improvements in conventional disarming capabilities raise questions on feasibility of future nuclear arms reductions. Third, it increases the stronger side’s temptation to launch a preemptive attack and also fuels the arms competition. The authors also challenge an assertion of the “theory of nuclear revolution”: that nuclear weapons are inherently survivable, arguing that the fear of disarming strikes keeps states engaged in strategic rivalry and results in unabated security competition.

To ensure nuclear survivability, states have traditionally employed three approaches: hardening (deploying nuclear forces in difficult to destroy structures), concealment (preventing the location of nuclear forces), and redundancy (using multiple systems to complicate the adversary’s strike plans). Technological advancements in counterforce capabilities are now undermining these strategies and initiating a new age of vulnerability. While increased weapons accuracy threatens nuclear forces that rely on hardening, revolutions in remote sensing threatens forces which depend on concealment. This age of vulnerability makes it plausible to use ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) as counterforce weapons.

The authors also challenge an assertion of the ‘theory of nuclear revolution’: that nuclear weapons are inherently survivable, arguing that the fear of disarming strikes keeps states engaged in strategic rivalry and results in unabated security competition.

The “accuracy revolution” has made low-casualty counterforce attacks plausible and nuclear weapons more usable. Likewise, revolutions in remote sensing technologies are making SSBNs and other mobile-launched missiles more detectable. As these technologies proliferate, the survivability of mobile platforms will become even more difficult. This scenario, therefore, favors the powerful and those with greater resources.

The new era of counterforce will compel states to deploy weapon systems that may remain survivable for generations. The reduced survivability of nuclear weapons also calls into question the rationale for cutting the size of nuclear arsenals. This suggests that technological arms racing will continue, and exercising restraint will not yield much benefit. Therefore, the authors argue, the United States should consider pursuing more advanced counterforce systems to bolster deterrence.

Three Unconsidered Aspects of Counterforce

While the authors adequately explain the implications of the growing vulnerability of nuclear assets and its ramifications on deterrence, there are three additional aspects, discussed below, that merit consideration within the new era of counterforce. These include the implications of counterforce developments on doctrinal restructuring, deployment patterns and readiness postures, and the plausibility of carrying out a disarming first-strike.

Growing counterforce capabilities can be viewed within the context of the renewed global focus on doctrinal shifts, particular the no-first-use (NFU) of nuclear weapons, in recent years. Counterforce capabilities complement a doctrine based on the flexible use of nuclear weapons, while a NFU pledge requires a state not to pursue the weapons or technologies that could be used to carry out a first strike. For a NFU pledge to be credible, it should be paired with a minimization in the salience of nuclear weapons in the country’s defense policy. On the other hand, the enhancing of counterforce capabilities indicates a shift in a state’s targeting strategy and may undermine the credibility of its commitment to uphold the NFU pledge: the fact remains, as pointed out by Leiber and Press, that counterforce capabilities amplify the temptation as well as ability to launch a preemptive first strike, rendering any adversary suspicious of that state’s unilateral commitment to not use nuclear weapons first during crisis. Therefore, as the new era of counterforce unfolds, the prospect of NFU remaining a credible and enduring nuclear doctrine becomes increasingly bleak.

Counterforce capabilities amplify the temptation as well as ability to launch a preemptive first strike, rendering any adversary suspicious of that state’s unilateral commitment to not use nuclear weapons first during crisis. Therefore, as the new era of counterforce unfolds, the prospect of NFU remaining a credible and enduring nuclear doctrine becomes increasingly bleak.

The article rightly points out how counterforce capabilities determine the size of arsenals and types of targets, but their effects on deployment patterns and readiness postures cannot be overlooked. Counterforce may require putting nuclear weapons on hair-trigger alert, which is inherently prone to risks of accidental use or escalation during crises. In an environment where the unauthorized use of weapons constitutes the most potent nuclear danger, counterforce postures based on a heightened state of readiness exacerbate the risks of unwarranted strikes. Additionally, this strategy also urges an opponent to reconsider alert levels, with an obvious tilt towards higher readiness, to shorten its response time to retaliate against possible nuclear first strike. Therefore, deploying counterforce capabilities may invoke the launch of vulnerable forces, even in response to a false warning.

The new era of counterforce, as the authors argue, has made low-casualty nuclear attacks probable. However, the authors do not adequately emphasize why this approach remains dangerous. Despite having pinpoint accuracy and enhanced remote sensing technologies, is it possible to wholly dismantle an adversary’s nuclear forces? Some argue that a portion of an adversary’s weapons would still remain, with which they could retaliate. For instance, an attack with limited damage to an adversary’s nuclear forces could prove counterproductive, as the adversary would retaliate to such an attack by launching its own forces, thus diminishing the perceived benefits of a low-yield strike. Additionally, the peacetime implications of such developments, as the authors assert, include the triggering of arms races. This can be seen in China’s nuclear modernization, which was triggered by growing U.S. counterforce capabilities and is now creating further security challenges in the Pacific.

The Dawn of Counterforce in South Asia

The nature of inter-state relationships, changing trends in the development of counterforce capabilities, and their implications for deterrence, as identified by Lieber and Press, are quite relevant to South Asia’s strategic environment. Although nuclear deterrence can be viewed as a force of stability in the region, the adversarial nature of the India-Pakistan relationship has not changed, suggesting that nuclear weapons alone cannot ensure regional stability in South Asia.

The pursuit of these new technologies suggests that India may be gradually drifting towards a counterforce targeting strategy. This would further undermine the credibility of its NFU commitment and escalate an arms race in South Asia.

Changes in force postures and the introduction of counterforce technologies is pervasive in South Asia as well. India officially declared its NFU pledge in 2003, after Prime Minister Vajpayee unofficially announced it in 1998. However, this commitment to a NFU policy has been hotly debated since then, with some analysts suggesting that India is moving towards a first-use or even a first-strike nuclear strategy. Moreover, Indian officials have at times openly questioned the utility of the country’s NFU pledge, while at the same time acquiring new technologies in line with nuclear counterforce targeting strategies. The development of technologies mentioned by Leiber and Press as counterforce capabilities, such as multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), ballistic missile defense (BMD), ballistic missiles with greater precision and accuracy such as the canisterized Agni-V equipped with advanced technologies to enhance its precision strike capability, nuclear-capable guided cruise missiles such as Dhanush and BrahMos, and other advancements in remote sensing technologies, indicate India’s growing ability to target an adversary’s nuclear forces. Furthermore, significant improvements in India’s intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities would make the task of survivability, as Lieber and Press assert, more challenging for its adversaries. These include satellites with high resolution imagery and synthetic aperture radar and growing antisubmarine warfare capabilities. The pursuit of these new technologies suggest that India may be gradually drifting towards a counterforce targeting strategy. This would further undermine the credibility of its NFU commitment and escalate an arms race in South Asia.

Pakistan, on the other hand, does not declare any commitment to NFU; it claims to have nuclear capability only for the purpose of deterrence. Besides Pakistan’s acclaimed policy of full spectrum deterrence in line with the dictates of credible minimum deterrence, its inadequate space-based ISR capabilities—despite recent improvements—and nuclear arsenal that is not based on canister-based delivery systems prevent Pakistan from realistically thinking of launching a preemptive strike against Indian nuclear forces dispersed on huge land mass. Considering India’s above-mentioned counterforce capabilities, Pakistan appears to be the relatively weaker state in this domain, lacking in both the intent and capability to launch a preemptive counterforce strike. In this scenario, as Leiber and Press have pointed out, Pakistan’s concern is to ensure survivability of its arsenal against possible first-strike.

The article rightly asserted that powerful states are likely to lead the technological race in this new era of counterforce. Nevertheless, these states must realize that they have a greater responsibility to show restraint and denounce strategies and capabilities that make war more likely and increase the chances of inadvertent uses of nuclear weapons. Thus, policies to exercise restraint, such as the NFU pledge, require that counterforce targeting be renounced.

Editor’s Note: In an ongoing series aimed at bridging the divide between policy analysis and academic scholarship, SAV contributors review recent articles and books published by leading scholars to evaluate the latest theoretical and analytical debates on strategic issues and their implications for South Asia. Read the series here.

***

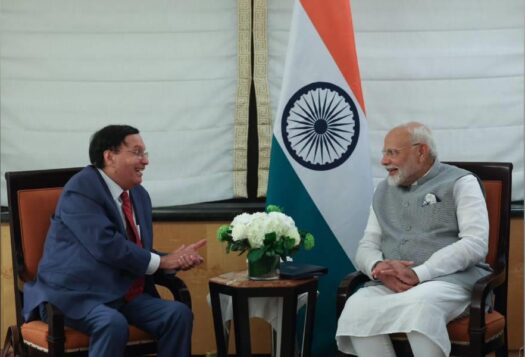

Image 1: Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: Bloomberg via Getty