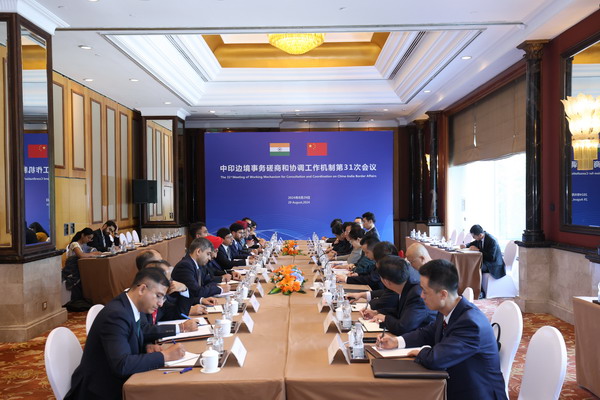

In the past few months, there has been a sudden uptick in official interactions between India and China. Their foreign ministers met twice in July, followed by the 30th and 31st rounds of the Working Mechanism for Consultation & Coordination (WMCC) on India-China Border Affairs on July 31 and August 29. This has led to speculation that the two countries are on the verge of reaching an agreement to end their border standoff ongoing since 2020, particularly at Demchok, one of the two remaining friction points along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Even before the two recent rounds of the WMCC and the meetings between the foreign ministers, New Delhi had started accepting Chinese proposals to invest in India. These developments have raised questions about whether India and China are re-engaging economically after restrictions imposed by India in the spring of 2020 and if their bilateral ties are on the mend. While there are signs of a slow rapprochement, the two sides appear to be taking a cautious approach. In any case, China’s great power ambitions, churn in the international order, and a widening trust deficit between New Delhi and Beijing dampen the likelihood of India and China returning to the pre-2020 status quo.

Shifting Economic Signals

Before the Galwan Valley clash between Indian and Chinese forces in June of 2020, New Delhi had, in April, already restricted Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflow from countries sharing borders with India. The law required the prior approval of the central government to invest in India, which functioned to prevent China’s potential hostile takeover of Indian companies during the pandemic. After Galwan, the Indian government further tightened the noose by introducing the Chartered Accountants, the Cost and Works Accountants, and the Company Secretaries (Amendment) Bill. This bill sought to bring in more transparency and accountability from chartered accountants (CA) and company secretaries, responding to the more than 200 CAs who had aided Chinese firms in violating the 2013 Companies Act, and another 400 CAs that had helped in incorporating Chinese shell companies in India.

China’s great power ambitions, churn in the international order, and a widening trust deficit between New Delhi and Beijing dampen the likelihood of India and China returning to the pre-2020 status quo.

However, recent indications by the Indian government seem to point towards some economic softening. In the recently released Economic Survey 2023-2024, the Ministry of Finance surprisingly called for an “inflow of FDI from China to increase India’s global supply chain participation along with a push to exports.” Additionally, India has started giving clearances to Chinese investments in the electronic manufacturing sector, indicating that New Delhi could potentially be open to stabilizing the relationship if the current standoff in eastern Ladakh, which has been ongoing since April 2020, ends. So far, China and India have resolved active conflict in Galwan, Pangong Tso, Hot Springs, and Gogra. The Indian position on the remaining friction points is that New Delhi has primarily taken the first step in stabilizing the relationship, so China should follow suit and disengage from the remaining standoff areas—Depsang and Demchok—in Ladakh.

The recalibration between India and China has been slow, but it is not a sudden phenomenon. China’s foreign minister visited India in an unannounced trip in March 2022 to discuss the border dispute. While China wants the border issue to be seen separately from broader ties, India has stressed that the boundary issue and broader relations cannot be separated. While India is still firm on this stance, it may be looking to reengage with China due to two reasons. First, India wants to take advantage of the China+1 strategy that many companies are now employing to de-risk their supply chains in the aftermath of the pandemic. This coupled with intensifying U.S.-China competition has led to companies looking for other avenues. India with its geographic size and population is an attractive alternative. India wants to attract FDI from other countries including China, especially as the United States and the European Union are putting duties on goods originating from China. Here, India could potentially become a manufacturing node for Chinese companies that manufacture in India and export worldwide. Second, like China in the 1990s and early 2000s, India sees a period of opportunity to develop rapidly for which stable borders are needed. In the early 1990s, China resolved many of its territorial disputes so it could focus on reforms and economic development. This included signing border agreements with India in 1993 and 1996 to keep the border stable. India is now in a similar position and may be looking for peace on the border to focus on rapidly amassing economic power.

However, while trade between the two countries has increased since 2020 in China’s favor, India’s policy of self-reliance and desire to make domestic manufacturing globally competitive prevent the possibility of long term trade normalization with China. This self-reliance will not happen immediately. It will take time for India to develop manufacturing capabilities and supply chains to replace its current dependence on China for intermediate goods and so in the interim, India’s trade deficit with China will increase. But in the long-term, India would look to diversify its import sources, as indicated by India’s recent pursuance of a number of Free Trade Agreements with various countries.

Strategic Caution in Re-Engaging China

While the prospect put forward by India’s Ministry of Finance is intriguing, engaging with China comes with its perils. Chinese investments come with risks attached, such as related to data security, data privacy, cyber espionage, and data harvesting. For instance, WeChat and TikTok secretly harvested user data from India before the Indian government banned them. In such a scenario, the Indian government must have a careful approach in re-engaging with China.

As New Delhi starts greenlighting Chinese investments, it would have to ensure that China does not invest in strategic sectors pertaining to national security—such as energy, communications, and defense. The government must review this list of protected sectors periodically to add or remove sectors. Additionally, the government should put measures in place to safeguard Indian companies in sectors where China has a competitive advantage. For instance, India’s domestic toy industry is growing rapidly, with a 57 percent decline in imports of toys from 2018-19 to 2022-23, while exports have surged by 60 percent in the same period, going from USD $203.46 million to $325.72 million. However, China’s toy industry is massive, generating revenue of USD $44.8 billion in 2023. Due to these circumstances, if China is allowed to set up its toy manufacturing unit in India, it will have an adverse impact on domestic companies. The Indian government can potentially deal with this situation by requiring China to have joint ventures in such sectors as a pre-requisite for investment, not only to protect Indian industries but also to expose them to technological knowhow.

Is an India-China Reset Expected?

Both India and China have attempted to resolve their outstanding issues. India lifting restrictions on Chinese investment and China issuing a statement to “work together to turn over a new leaf in the border situation” after the 31st WMCC suggests that both countries are trying to mend relations.

The competition between India and China in Asia will persist irrespective of the border issue, as China’s strategic ambitions in the region, including its efforts to expand influence, will continue to clash with India’s security and geopolitical concerns, making any strategic thaw difficult.

However, there have been fundamental changes in India-China relations since 2020 that are hard to reverse. For one, Beijing initiating the eastern Ladakh standoff and its induction of additional troops and infrastructure at the LAC since 2020 have increased the trust deficit between New Delhi and Beijing, both at the strategic and tactical levels. For another, China’s belligerence at the border with India and intensifying competition between the United States and China have drawn New Delhi and Washington closer, particularly in the realm of defense cooperation. This growing Indo-U.S. defense collaboration is perceived by China as a key component of Washington’s broader containment strategy against Beijing. From China’s perspective, India’s increasing alignment with the United States, particularly in the Indo-Pacific, complicates any potential rapprochement between the two Asian powers.

From New Delhi’s point of view, two conditions must be met for the beginning of a thaw in India-China relations. The first is if China agrees to complete disengagement from the LAC, which entails resolving the remaining two standoffs at the strategically important Depsang and Demchok. The second is complete de-escalation by de-induction of the additional troops brought in by China post-2020 and recommitment to the border understandings that India and China have developed since the early 1990s.

However, given the current realities, it remains unlikely that India-China relations will soon return to the pre-2020 status quo. Even if tactical economic cooperation between India and China resumes, the strategic rebalance will not be successful because the core issue of the border dispute remains unresolved. Furthermore, the competition between India and China in Asia will persist irrespective of the border issue, as China’s strategic ambitions in the region, including its efforts to expand influence, will continue to clash with India’s security and geopolitical concerns, making any strategic thaw difficult. Finally, the changing global order—marked by the decline of unipolarity and the rise of multipolar competition—makes restoring trust between India and China an even more complex undertaking. In this context, New Delhi will have to carefully manage its relationship with China as it oscillates between competition and limited cooperation. While economic ties and multilateral engagements may offer avenues for collaboration, the underlying strategic rivalry will continue to shape their interactions. Ultimately, a full normalization of relations seems improbable, but pragmatic engagement will be essential to prevent the relationship from deteriorating further and to ensure regional stability.

Also Read: To Save CPEC, Pakistan’s China Policy Needs an Overhaul

***

Image 1: MEAphotogallery via Flickr.

Image 2: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The People’s Republic of China.