Pakistan is a cornerstone of China’s approach to South Asia, a region whose natural resource abundance and proximity to vital maritime routes have rendered it both geostrategically and economically significant to Beijing. This has made Pakistan an important element of China’s “Asian Dream,” the long-held Chinese ambition of regaining its historical status as the principal leader of the continent. Beijing’s broad South Asia policy is centered on both the economic rationale of increasing regional connectivity with South Asian countries and the strategic interest of countering Indian influence in Asia.

Indeed, analysts have proposed that Beijing’s inclination towards Pakistan is deeply embedded in its strained relationship with India, another emerging Asian power with the potential to resist China’s rise in the continent. Chinese policymakers thus appear to have their eyes fixated on the implications of mounting Indo-U.S. alignment (as exhibited by President Trump’s new Afghanistan policy, for instance), enduring India-Pakistan tensions along the border in Kashmir, and China’s own border dispute with India. For China, a country that views regional leadership in South Asia as a stepping stone to its larger goal of attaining Asian and global dominance, Pakistan is key to increasing its influence in South Asia and countering the Indo-U.S. strategic partnership.

China’s Strategic and Economic Role in Pakistan

Since establishing diplomatic relations in 1951, China and Pakistan have enjoyed a warm relationship. Though Pakistan remained in the U.S. bloc during the Cold War, the 1962 Sino-Indian border war and India’s inclination towards the former Soviet Union, with whom China’s relations deteriorated after 1960, were factors that contributed to China’s decision to provide diplomatic assistance to Pakistan during its war with India in 1965 and 1971.

China began supplying Pakistan with arms in the 1960s and became the country’s principal arms supplier after the United States imposed sanctions on Pakistan in 1990. It is also widely believed that China played a major role in developing Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program. To China, a partnership with Pakistan served the purpose of checking both U.S. intimacy with Pakistan and Indian aggression towards China. Pakistan became China’s point of contact with the United States in the normalization of relations between the two countries via Henry Kissinger’s visit to China in 1971.

Though earlier the relationship was primarily a strategic asset to China, Beijing began to ramp up its economic engagement with Islamabad in the 1990s. China has now partnered with Pakistan to pursue the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a $62 billion project that encompasses transport networks, infrastructure schemes, and energy initiatives that will spread throughout Pakistan and are expected to promote economic development. As part of China’s larger regional project the Belt and Road Initiative, CPEC will lay the foundation for a greater Chinese presence in South Asia while also asserting China’s dominance over India in the region. This initiative has enhanced Islamabad’s strategic importance to Beijing by making trade with mainland China from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central Asian states much more efficient. Significantly, CPEC has also connected Chinese markets to Africa and the Gulf via the Gwadar Port, the first shipment from which occurred in late 2016.

China’s economic engagement with Pakistan remains intertwined with its strategic interests in South Asia vis-à-vis India and the United States. Indo-U.S. ties in South Asia have long irked Pakistan, with Islamabad viewing their relationship as Washington’s encouragement of the hegemonic designs of New Delhi, Islamabad’s longstanding rival. China, in alignment with Pakistan, views this cooperation as a strategy aimed at containing its own economic and military rise in the region. Consequently, both Pakistan and China object to U.S. President Trump’s new Afghanistan policy, which simultaneously enhances India’s role in Afghanistan and rebukes Pakistan’s counterterrorism efforts in Afghanistan. In a recent bilateral dialogue between Chinese and Pakistani think tanks in Islamabad, Major General (Retd) Li Mengyan articulated that the United States has taken an unbalanced approach to Afghanistan by unfairly blaming Pakistan while Major General (Retd) Zhao Ning said that the United States is clearly placing India and Australia at the center of its new Indo-Pacific strategy. Thus, as India and the United States’ interests are aligning, the partnership between China and Pakistan has only grown closer.

Evolving China-Pakistan Dynamics

Though China’s support for Pakistan in the face of Indo-U.S. antagonism has been quite consistent, Chinese President Xi Jinping recently endorsed a BRICS declaration that called out Pakistan for supporting cross-border terrorism. This was a digression from China’s previous strategy of shielding Pakistan from international condemnation at the United Nations and other international fora. However, in a joint press conference during Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Khawaja Asif’s recent visit to Beijing, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi reaffirmed China’s close partnership with Pakistan and applauded Pakistan’s efforts in fighting terrorism globally. China appears to be caught in a balancing act between its strong bilateral relationship with Pakistan and the pull of multilateral institutions. How heavily China decides to weigh its vested interest in a strong strategic partnership with Pakistan while dealing with the United Nations, BRICS, and other international organizations in the future will be interesting to observe.

Regarding the developing situation in Afghanistan, China and Pakistan have stated their commitment to launching an “Afghan-led and Afghan-owned” peace and reconciliation process and have called upon the Afghan Taliban to join them in advancing this process. Though it is unclear how this notion will develop, any such initiative by China and Pakistan would likely be met with opposition from President Trump, whose recent military strategy doesn’t even really consider reconciliation as an option in Afghanistan. In addition, Trump’s call for India’s increased involvement in Afghanistan concerns both China and Pakistan, essentially pitting the United States and India against China and Pakistan in Afganistan.

Another evolving piece of the China-Pakistan puzzle is defense cooperation. China and Pakistan were each apprehensive after the United States and India signed a logistics agreement in 2016 to enhance the interoperability of the two countries’ militaries. It may, therefore, be in China’s strategic interest to make a concerted effort to strengthen its defense ties with Pakistan. The recent Doklam stand-off between China and India shows how these two Asian giants have not abandoned their age-old competition for Asian dominance. In the wake of rising Indo-U.S. defense cooperation, China may begin to replace U.S. military aid to Pakistan.

China in South Asia: The View from Islamabad

Pakistan has welcomed China’s larger role in South Asia as a means of balancing India’s regional economic and strategic ambitions. Pakistan sees China’s expansion of the BRI in Sri Lanka, for instance, as killing two birds with one stone: it enhances China’s role in the region and irritates India, which does not want to compete with China for influence in its neighborhood.

However, Pakistan would like for China to show a greater commitment to bringing about peace and stability in Afghanistan after the U.S. failure to achieve results in the country for more than a decade. The recent Rohingya issue has admittedly highlighted a disparity of stance between Pakistan and China since Beijing considers Myanmar an important ally whereas thousands of Pakistanis have voiced support for displaced Rohingyas. Nevertheless, this all-weather partnership remains strong: both Pakistan and China see each other as a means of advancing their agenda in South Asia.

Editor’s note: This is the first installment of South Asian Voices’ new six-part series China in South Asia. In this series, our contributors Fatima Raza from Pakistan, Kithmina Hewage from Sri Lanka, Avasna Pandey from Nepal, Saimum Parvez from Bangladesh, Ahmad Shah Angar from Afghanistan, and Pushan Das from India explore China’s strategic and economic goals in their respective countries, the challenges China may face in implementing those goals, and how China’s engagement will affect the regional balance of power in South Asia. Read the entire series here.

***

Editor’s Note: Click here to read this article in Urdu

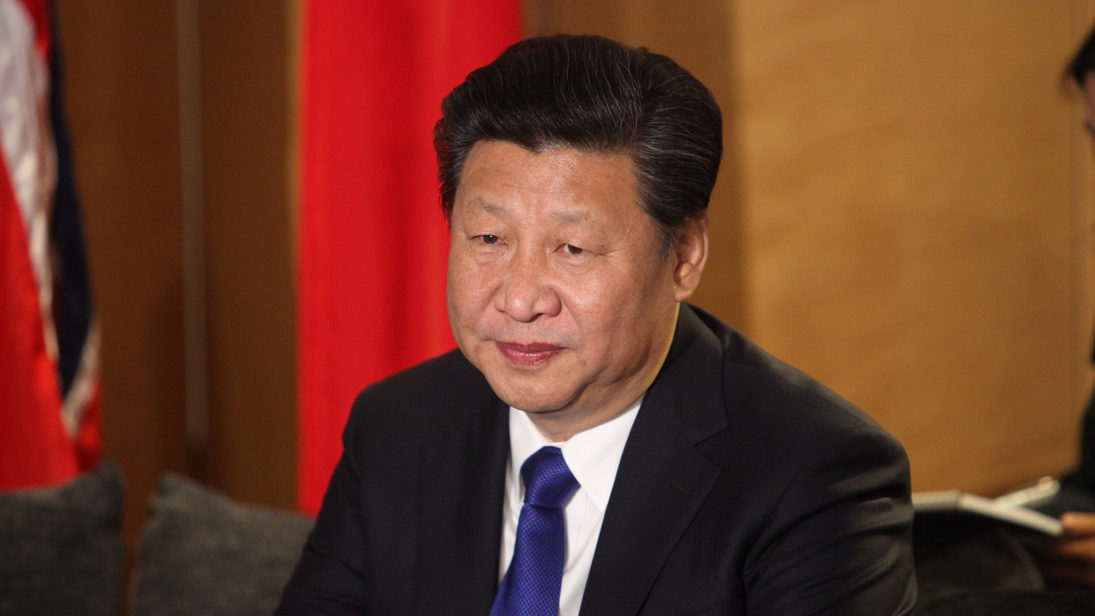

Image 1: The British Foreign and Commonwealth Office via Flickr

Image 2: Lintao Zhang via Getty Images