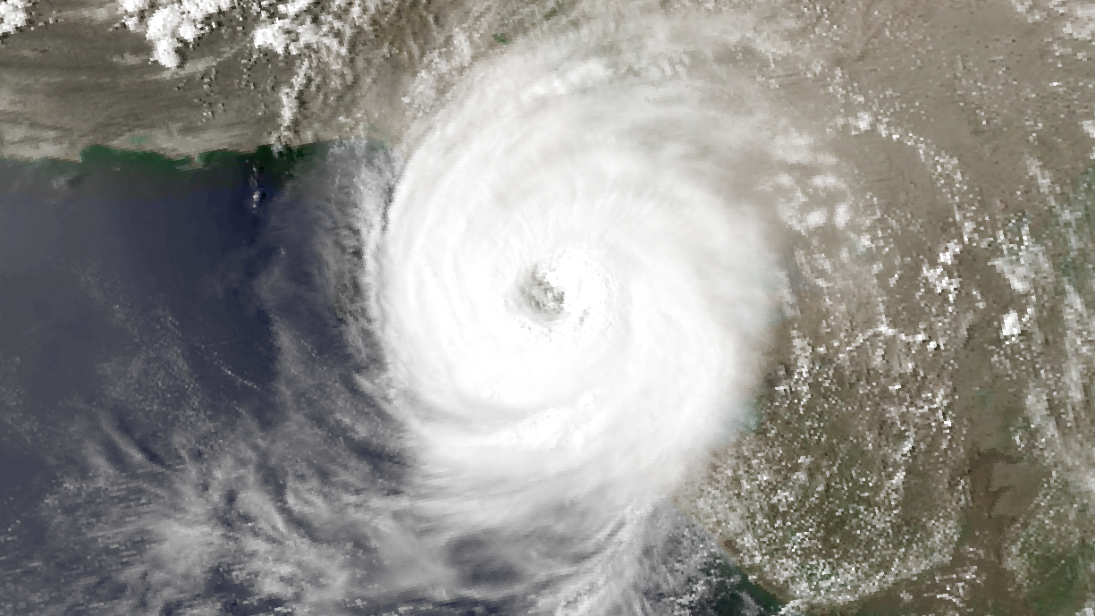

In June 2023, Cyclone Biparjoy swept across Indian and Pakistani coastlines, causing heavy flooding with wind speeds topping 80mph. Fortunately, both India and Pakistan readied their disaster preparedness systems in time to provide rescue and relief measures and relocate vulnerable populations. In the end, these mitigation efforts proved effective in limiting the destruction of the cyclone. However, they also show the need for greater cooperation between Islamabad and New Delhi as the risk of climate events intensifies.

Disaster relief and mitigation are just some of the components involved in averting major climate-related catastrophes. On this issue, India and Pakistan can find common ground for cooperation without their traditional problems hindering their efforts. Just as the two countries continue to cooperate on some issues through bilaterally established forums like the Permanent Indus Commission, such forums can also be imagined for climate change and disaster management.

The isolated responses to Cyclone Biparjoy resulted from the larger distrust between India and Pakistan. While cooperation and coordination on climate issues stand to benefit both countries, India and Pakistan continue to prioritize their rivalry. The disaster response following the cyclone was a missed opportunity for cooperation between the two sides. In the future, India and Pakistan must come together to mitigate the impact of ecological disasters related to climate change.

While cooperation and coordination on climate issues stand to benefit both countries, India and Pakistan continue to prioritize their rivalry.

If the two neighbors choose to fight the perils of climate change together, their efforts may act as a confidence-building measure to ease their otherwise fractious relationship. Both states could benefit from reframing climate change as a humanitarian issue that impacts ordinary citizens rather than viewing it from a traditional realpolitik lens. Some of their mutual issues include stubble burning, industry-related challenges, garbage and sewage management, rainfall, and drought management, as well as more serious challenges from natural disasters.

A Cooperative Past

In the past, India and Pakistan have cooperated on climate change and disaster mitigation. For instance, Pakistan assisted India after the Gujarat earthquakes in 2002. Cooperative and reciprocal relief efforts were carried out by both countries after the earthquake in Kashmir in 2005. Similarly, both countries also came together in 2010 to jointly mitigate the impact of the floods — when Pakistan’s Punjab and Sindh provinces faced inundation. In 2014, India also offered assistance to Pakistan during its floods.

In addition to supporting each other after natural disasters, both states suffer from the same climate-related issues. India and Pakistan have large amounts of stubble burning in their countries. In countering the practice, Pakistan has failed to issue the penalties that it has legally imposed. Similarly, India has failed to execute its policies due to sociopolitical hurdles.

Through its National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) framework, Pakistan has some success stories in its disaster mitigation but the sheer size of disasters leaves state efforts dwarfed in comparison to the devastation. On the other hand, India now relies on domestic organizations like the Indian National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) at the national level and Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) at the international level. These organizations have been especially valuable in the Indian Ocean Region with the Indian Navy emerging as the ‘net responder’ to natural disasters like floods and cyclones for geographically distant countries like Mozambique and Myanmar. With stronger internal institutions, New Delhi is less pressed to cooperate with Pakistan in the aftermath of climate events.

While both countries have recorded success individually, the culture of cooperation on issues of non-traditional security like climate change and disaster mitigation has faded. The reluctance of both governments to engage with each other on bilateral or multilateral issues in recent years is evidence of how they perceive any chance of mutual consensus. India’s policy of strategic distancing from Pakistan has truncated the possibility of cooperation, even on non-sensitive issues like climate change and disaster mitigation. Introduced in 2018, New Delhi’s strategy has broadened and deepened the diplomatic wedge between the two. For instance, India only provided limited assistance to Pakistan after the country was inundated again by the floods in 2022 even though the floods resulted in the death of 1,100 people and displaced 33 million others. Despite the severe damage caused by the floods, India offered mere verbal condolences — depicting India’s reluctance to provide real-time assistance after a major natural disaster. Pakistan has also opted for verbal condolences with little to no intention of extending a sympathetic hand in the form of humanitarian assistance.

The Need for Collective Action on Environmental Threats

South Asia is an ecologically sensitive zone prone to natural disasters and climate emergencies. The region has witnessed a rise of flash floods and landslides with cloud bursts resulting in sudden rainfall within a short duration of time. Rising temperatures have caused glaciers to melt, forming overflowing glacial lakes that risk Glacial Lake Outburst Flooding (GLOF). Both Pakistan and India are at the epicenter of GLOF-related catastrophes and this can only add to their current climate-related problems. Moreover, the 2013 North India floods and the 2022 Pakistan floods showcase the severity of climate shocks. The former saw a death toll of over 5,000 people, and the latter affected 20.6 million including nine million children. With strained economies, overpopulation, and poor infrastructure, climate events risk catastrophic devastation in South Asia.

India and Pakistan could mitigate climate-induced disasters and resulting conflicts by adhering to prevalent bilateral frameworks — like the Indus Waters Treaty and the Rann of Kutch agreement — enabling viable discourse on climate change.

Although India and Pakistan represent a whopping 20 percent of the global population, limited importance is attached to finding a collective response to climate change within the region. While India and Pakistan are individual signatories to the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change, collective action on climate change is limited as both states vacillate on questions of integrated climate action. There is sufficient common ground for both states with respect to climate-related challenges and both states can address these vulnerabilities with a shared approach without involving some of their conventional problems that usually result in a stalemate and inability to cooperate.

The Way Forward

Pakistan and India are fairly cognizant of the climate-related challenges they face and have voiced their concerns at international forums. Both states have signaled a similar approach to dealing with these issues at such forums but have yet to address the issue bilaterally.

India and Pakistan could mitigate climate-induced disasters and resulting conflicts by adhering to prevalent bilateral frameworks — like the Indus Waters Treaty and the Rann of Kutch agreement —- enabling viable discourse on climate change. Establishing an environmental data-sharing mechanism could create real-time situational awareness on various issues. These issues could target immediate concerns like early rainfall warnings, stubble burning, heatwaves, and drought periods as well as more long-term issues like GLOF prediction data, earthquake timetables, cyclone schedules, and changing weather patterns. Sharing such data annually or biannually not only allows both states to create situational awareness but also helps in their individual disaster management profile.

India and Pakistan can also engage in international forums like the Conference of Parties (COP), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and sub-organizations within the United Nations. Another option available to both states is to seek assistance from third-party interlocutors relevant to their issues like the World Bank, USAID, and other forums that have a direct stake in humanitarian issues of the two states. A Climate Track-II can also be envisioned before the formal engagement commences to reinforce an expert view on issues that have a short-term to long-term impact on both states and their environmental fault lines. SAARC has also had a significant impact on environmental issues. The SAARC Environment Action Plan read with the SAARC Convention on Cooperation on Environment 2010 can be upgraded to address current and future challenges in the light of recent disasters and a theoretical consensus can be achieved.

An agreement to revive SAARC has always seemed unattainable. However, the forum still stands as one of the most adequate for such issues especially when climate disasters are imminent. Environmental disasters will continue to manifest in many shapes and intensities, and they will continue to demand collective action as no one state has the resources necessary to prevent climate change alone. For South Asia, the key to saving billions is not in taking isolated action but in creating an atmosphere of mutual consensus beyond traditional competition.

Also Read: South Asia Must Proactively Prepare to Face Climate Change.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: Cyclone approaching Pakistan via Wikimedia Commons.

Image 2: The flags of India and Pakistan at the Wagah Border via Flickr.