In September, the United States confirmed that it was cancelling security assistance to Pakistan over its “lack of decisive actions” against militants. This decision came months after the U.S. Department of State’s announcement in January that it was suspending security assistance to Pakistan after President Donald Trump tweeted about how the United States had “foolishly given Pakistan more than 33 billion dollars in aid over the last 15 years” while Pakistan provided “safe haven to the terrorists…in Afghanistan.”

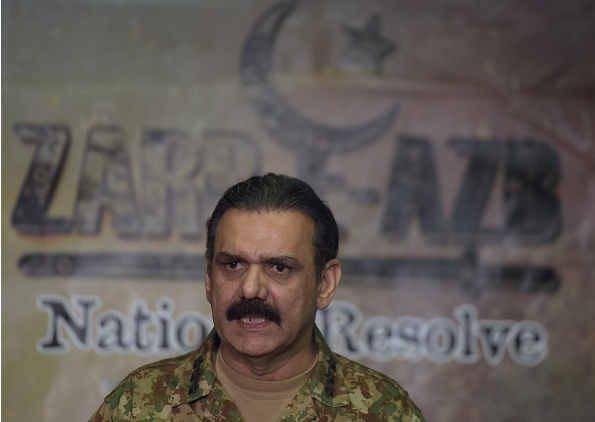

However, the incumbent U.S. administration expresses a counterproductive narrative that neglects the historical and geopolitical reasons for the emergence of militancy in Pakistan and the role of great powers in fueling instability in the country. Labeling Pakistan a terrorist “safe haven” antagonizes Pakistani policymakers and undermines international counterterrorism cooperation. Moreover, the failure to recognize the Pakistani army’s successes in countering terrorism, for example with Operation Zarb-e-Azb, is likely to alienate Pakistani soldiers and dilute their enthusiasm for the “war on terror.” Crucially, the “safe-haven” narrative ignores the fact that Pakistan itself has suffered tremendous losses because of militancy, with 22,504 civilians and 7,014 security personnel killed in terrorist violence in the country since 2000.

Given the U.S. government’s cancellation of military aid, as well as the broader power shift in the international order towards multipolarity, it is pertinent to ask whether global and regional powers have a responsibility and/or role to play in countering terrorism in Pakistan.

Great Power Responsibility

For international relations theorist Hedley Bull, great powers in the international society of states have “special rights and duties.” It is their responsibility to mold their policies in a way that enhances peace and security in the international system. Jason Ralph and James Souter develop this idea by arguing that some states have special responsibilities because of their special capabilities, or because these states “have harmed, or rendered vulnerable, a given individual or group.”

In Pakistan’s case, there are several ways in which global and regional powers have contributed to the rise of militant groups in the country, starting with decolonization in 1947. The departing British paid insufficient attention to the demarcation of the border between the new states of India and Pakistan. Jammu and Kashmir was always going to be contentious, given its Muslim majority, Hindu Maharaja, and location at the boundary between the new states. Furthermore, Afghanistan had long been disgruntled over the contours of the Durand Line. Pakistan’s territorial disputes with India and Afghanistan have driven militancy in the Pakistan-India-Afghanistan triangle for the past seventy years.

In Pakistan’s case, there are several ways in which global and regional powers have contributed to the rise of militant groups in the country, starting with decolonization in 1947 … A second way in which powerful states have destabilized Pakistan is through the Afghan jihad of the 1980s … Furthermore, the Iranian Revolution triggered a political rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia, both of who are believed to have sponsored sectarian violence in Pakistan in the 1980s and 1990s, the remnants of which continue to trouble Pakistan today.

A second way in which powerful states have destabilized Pakistan is through the Afghan jihad of the 1980s. Foreign support for Pakistan’s jihad against Soviet troops in Afghanistan poured in from the United States, Saudi Arabia, and China, among others, which propped up a diverse group of rebels that were trained in north-western Pakistan. A radical curriculum was developed at the University of Nebraska for use at madrasas in north-western Pakistan, which were radicalized and militarized during this period. This region of Pakistan paid a huge price for the Afghan jihad: traditional social structures broke down as warlords took the place of tribal elders, the Pashtunwali legal code that had functioned for centuries was undermined, and religion was militarized. After the end of the war in 1989, fighters from several parts of the world stayed on in Pakistan and Afghanistan, perpetuating militancy in the region. Most of the militant groups and leaders currently operating in Pakistan have their roots in the Afghan jihad.

Furthermore, the Iranian Revolution triggered a political rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia, both of who are believed to have sponsored sectarian violence in Pakistan in the 1980s and 1990s, the remnants of which continue to trouble Pakistan today. The Tehreek-i-Nifaz-i-Fiqh Jafariya (TNFJ) was established in 1979 to defend Pakistani Shias against former President General Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization program. The TNFJ violently resisted any attempt by the government to compulsorily collect the zakat (Islamic alms tax) from people’s bank accounts based on the Sunni Hanafi school’s legal interpretation of the Shariah. The TNFJ is believed to have received significant support from Iran. Alex Vatanka describes the period from the early 1980s until the mid-1990s as “the zenith of the Islamic Republic’s championing of Shia militancy in Pakistan,” calling it “a period when Tehran was verifiably engaged in supporting Pakistani Shia groups.” Meanwhile, the resistance in Afghanistan was Sunni and mujahideen from the Afghan war began establishing anti-Shia militant organizations in Pakistan, starting with the Sipah-i-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP) in 1985. According to Sana Haroon, it was Arab benefactors that sponsored these violent Sunni groups in Pakistan, which are still active in some form today. In fact Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, which was the third-deadliest group in Pakistan in 2016, is a breakaway faction of the SSP.

Supporting Counterterrorism Efforts in Pakistan

Given the historical role that global and regional powers have played in destabilizing Pakistan, they have a special responsibility to help the country in countering the threat of terrorism and militancy.

Given the historical role that global and regional powers have played in destabilizing Pakistan, they have a special responsibility to help the country in countering the threat of terrorism and militancy. This is not to deny Pakistan’s own agency in participating in the trilateral proxy war that has ensued in the Pakistan-India-Afghanistan triangle. However, it provides a counterbalance to the discursive construction of Pakistan as a terrorist “safe haven” by re-investigating the role that global and regional powers, including the United States, have played in the growth of militancy in Pakistan.

The Pakistan army’s counterterrorism operations have gone a long way towards quelling the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), but the deep roots of militancy might require a more holistic response. Moreover, the TTP remains a threat because it has shifted its infrastructure to Afghanistan, while question marks remain over whether Afghanistan- and India-focused groups such as the Afghan Taliban, the Haqqani Network, Lashkar-e-Taiba, and Hizbul Mujahideen have been targeted.

Going forward, international aid to Pakistan should be directed not only toward “hard” counterterrorism, but also toward de-radicalization, counter-radicalization, and humanitarian assistance to parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa that have been heavily affected by the global “war on terror.” The Pakistani military’s terrorist rehabilitation program is a major “soft” counterterrorism initiative that deserves the attention and support of the international community. Humanitarian assistance is vital because of the risk that civilian casualties and displacement caused by military counterterrorism may breed resentment and motivate further radicalization.

Furthermore, there is a need for peacebuilding in Pakistan in the aftermath of the Afghan jihad and “war on terror.” Great powers such as the United States, United Kingdom, and China and regional powers such as Saudi Arabia and Iran should support not only Pakistan’s terrorist rehabilitation program, but also the reform of madrassas that were radicalized in the 1980s, democratization, job creation, and poverty alleviation. Finally, it is incumbent upon the international community to mediate among Pakistan, Afghanistan, and India to bring about a resolution of the longstanding disputes over the Durand Line and Kashmir. This will indirectly resolve the problem of militancy and bring stability to the region.

***

Image 1: Inter-Services Public Relations, Pakistan

Image 2: Aamir Qureshi/AFP via Getty Images