A year after Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi secured a second term in a landslide election victory for his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), his government appears as popular as ever in light of its developing response to the coronavirus pandemic. Yet, just three months ago, India was ablaze with anti-government protests that gave way to deadly clashes between Hindus and Muslims in northeastern New Delhi. During a February 25 riot, mobs of Hindu men, brandishing iron clubs and clad with saffron stripes on their foreheads, attacked Muslim shops and homes, beating residents. Three days after the initial surge in violence, over 40 people had been killed and 200 injured—mostly Muslims. The Delhi police reported directly to Home Minister Amit Shah, long Modi’s right-hand man, who has done more to stoke Hindu nationalism on a communal level than any other member of government. This violence represents the most troubling development in months of mounting tensions in India. Most recently, the pandemic has proven yet another breeding ground for virulent anti-Muslim sentiment in the country.

This internal discord is symptomatic of an active reshaping of India’s national identity along Hindu lines. As a forceful Hindu nationalist turn has enflamed tensions within India, it may also further sour India-Pakistan relations. South Asia commentators are familiar with a particular narrative of India-Pakistan conflict dynamics: India has adopted an increasingly hardline stance towards Pakistan for harboring anti-India militant groups, while Pakistan has toughened its posture towards India for its governance in Kashmir. The BJP government’s current agenda may accelerate pre-existing pathways by deepening a foundational conflict over national identity.

The BJP government has taken a secular, patchwork-quilt India and reimagined it as a home for Hindus. This imagining places it squarely in opposition to the national identity of its neighbor. Pakistan was conceived in 1947 as a home for South Asian Muslims and has, since Partition, shifted from being a culturally Muslim nation to a religiously Islamic one that has embraced “anti-Indianism” as a national rallying point. The BJP’s recent policy agenda has placed religious restrictions on claims to Indian citizenship and identity, which in turn have fed an uptick in jointly anti-Muslim and anti-Pakistan rhetoric within India’s public sphere. Oppositional rhetoric on both sides of a sharpened India-Pakistan dichotomy is likely to cast a dark shadow over any future confrontations.

A National Redefinition

Since winning re-election, Modi has overseen the unfolding of a stark majoritarian agenda within India’s domestic sphere. His policy agenda is shaping India into a principally Hindu nation, an ideology called Hindutva and espoused by the right-wing Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

The BJP’s recent policy agenda has placed religious restrictions on claims to Indian citizenship and identity, which in turn have fed an uptick in jointly anti-Muslim and anti-Pakistan rhetoric within India’s public sphere. Oppositional rhetoric on both sides of a sharpened India-Pakistan dichotomy is likely to cast a dark shadow over any future confrontations.

This Hindutva agenda has come to dominate much of the public rhetorical space in India and taken an insidious and all-encompassing policy form. On August 5, 2019, the BJP suddenly revoked Article 370 of the Indian constitution, which granted India’s only Muslim-majority state, Jammu & Kashmir, semi-autonomous status. Kashmir was subsequently put under lockdown, restrictions related to which still remain. On August 31, the government implemented a National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam, requiring all of the state’s residents to provide physical proof of their citizenship. Since then, members of the government, including Home Minister Shah, have proposed a nationwide NRC. On November 9, the Indian Supreme Court ruled in favor of Hindu nationalists in a long-standing dispute over the site of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya. Mobs of Hindu nationalist rioters razed the mosque in 1992, claiming it was constructed atop the birthplace of Ram. And in December 2019, the Indian parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) granting fast-track citizenship to all Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Parsis, Jains, and Christians facing persecution in Muslim-majority neighboring countries. Protests erupted across India in response to the CAA, with demonstrators arguing the act expressly discriminates against Muslims and upends the country’s pluralist touchstones.

The CAA most starkly encapsulates the BJP’s national re-imagining in laying out religious criteria for Indian citizenship access. Combined with the NRC—which commentators see as a thinly veiled mechanism for stripping Muslims of their citizenship—the CAA could leave millions of Muslims stateless.

Has India Recast Itself in Pakistan’s Image?

While an India without religious barriers to citizenship may counterbalance Pakistani nationalism, a Hindu India presents a direct foil to a Muslim Pakistan. Indeed, as noted Indian journalist Barkha Dutt has argued, it appears as though India has cast itself in Pakistan’s image over the course of the last few months.

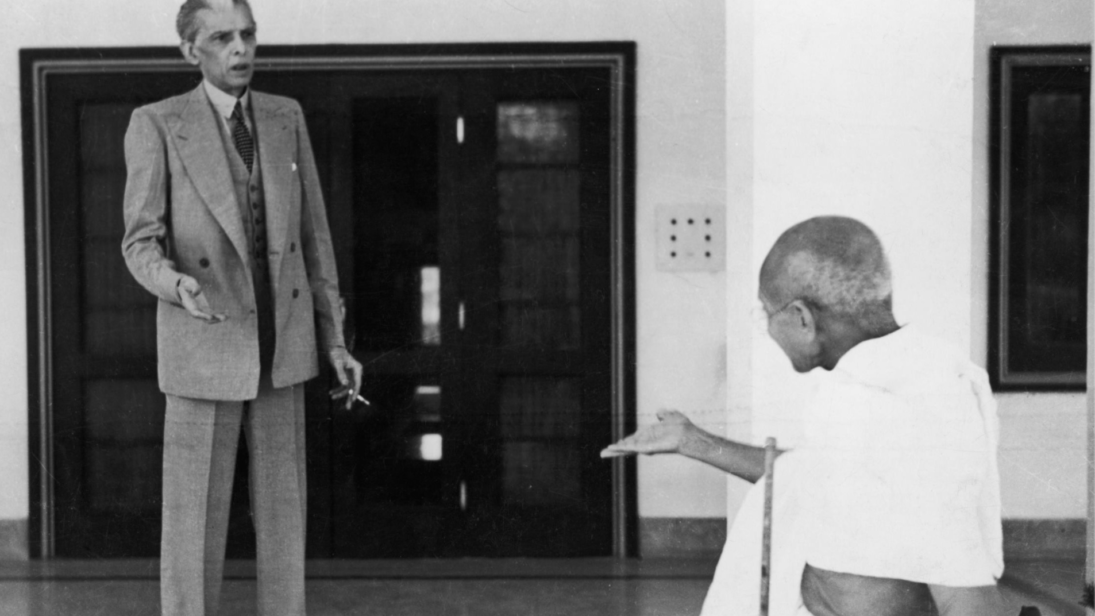

This may play into the hands of an anti-Indianism that has become, over time, an indispensable thread of Pakistani nationalism. Ashutosh Varshney, in the “Idea of Pakistan,” argues that, since 1947, “Islam and anti-Indianism have been the two master narratives of Pakistan’s polity.” 1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, conceived of the state as a home for South Asian Muslims, believing that Hinduism and Islam, more so than two religions, constituted two distinct social orders. 2 He believed that Muslims could not expect fair treatment in a Hindu-majority independent India. This “two-nation theory”—central to the initial founding of the Pakistani nation-state—has received its fair share of tests over time. Scholars have argued that cultural identity envisioned as religious identity paints far too restrictive a portrait of the modern subcontinent. Yet, over time, the failure of the Pakistani civil state has led Pakistan to cast aside its founding nationalism and enshrine a reactionary Islamic ideology within its security apparatus. So too has anti-Indianism become a source of national cohesion, and the India-Pakistan rivalry a “do-or-die” conflict. 3

Facing hardened Pakistani nationalism, a secular India enduringly guided by Gandhi’s and Nehru’s multicultural, democratic ideals provided some buffer against overt interstate conflict…peace with Muslim-majority Pakistan supports the secular Indian project, and hostility undercuts it.

Facing hardened Pakistani nationalism, a secular India enduringly guided by Gandhi’s and Nehru’s multicultural, democratic ideals provided some buffer against overt interstate conflict. Even as India and Pakistan have fought four wars, peace with Muslim-majority Pakistan supports the secular Indian project, and hostility undercuts it. As of 2019, there are more Muslims living in India than in Pakistan. Arguably, Muslims’ relatively peaceful coexistence alongside Hindus in India—including their mainstream participation in the public sphere as actors, artists, musicians, athletes and businesspeople—also discredits the two-nation theory.

Anti-Muslim Conflated with Anti-Pakistan

As Modi and his BJP government have set India on a Hindu nationalist course, they threaten to chip away at an important bulwark against conflict with Pakistan. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan has already, in public rhetoric, warned that the Indian government’s ongoing agenda threatens Pakistan, also promising a “befitting response” should India’s “domestic chaos” and Modi’s “fascist leadership” not settle peacefully. Khan has identified India’s “Hindutva Supremacist Fascist ideology” as additional grounds for escalation across the Line of Control (LoC) in Kashmir. While Pakistan has itself drummed up anti-Indian sentiment in recent months, it is also right to fear the consequences of a more emboldened Hindu nationalist neighbor.

Anti-Pakistan sentiment has accompanied widespread anti-Muslim rhetoric and violence in India, as pro-BJP factions and chief ministers have charged Indian citizens and public intellectuals opposing the government’s program with being “anti-India” and called for Indian Muslims to “go to Pakistan.” Backlash has begotten backlash in India’s public sphere, as peaceful anti-CAA demonstrations have given way to what many have even referred to as a pogrom. Modi himself has fanned the flames of divisiveness, adding an ethno-nationalist overtone to BJP anti-Pakistan messaging.

The Modi government has cultivated a zero-sum nationalism for India, tacitly enabling communal violence and overseeing an overtly Hindu nationalist policy program. Any citizens who are not pro-government are deemed “anti-national.” Muslim dissenters and “anti-nationals,” are accused of being “pro-Pakistan.” Reporters critical of the BJP have faced widespread online abuse from BJP supporters. Journalist Rana Ayyub, who published “the Gujarat Files” assessing Modi’s and Shah’s tenures at the helm of the state, was told to “go back to Pakistan.” Prominent Gandhi scholar Ramachandra Guha was detained while speaking to NDTV on air about the Indian constitution and holding a poster of Gandhi. Writer Aatish Taseer lost his Overseas Citizenship of India status after publishing anti-Modi content, after which Modi supporters denounced him as a Pakistani spy. All the while, ministers have called the anti-CAA protests part of a Pakistan-sponsored conspiracy and charged a civilian with sedition for indicating favorable attitudes towards Pakistan.

This BJP government’s strident ideology mirrors Pakistani ideological anti-Indianism and also validates the two-nation theory, supporting the notion that Hindus and Muslims require separate countries to coexist on the subcontinent.

Even in the absence of directly confrontational rhetoric at the government level, these exchanges provide a window into a brand of “anti-Pakistanism” that may accompany India’s Hindu nationalist turn. This strident ideology mirrors Pakistani ideological anti-Indianism and also validates the two-nation theory, supporting the notion that Hindus and Muslims require separate countries to coexist on the subcontinent. As Muslims are targeted as “anti-nationals,” they embody, for the staunchest Hindutva standard bearers, the “antithesis” of India—Pakistan—simply by virtue of their religious and cultural heritage. The CAA further codifies this dichotomy by enshrining a religious prerequisite for Indian citizenship.

Conclusion

An increasingly majoritarian Indian national identity is likely to reverberate deeply within and beyond the domestic sphere, shaping the manner in which India interacts abroad. Within Modi’s India, decisions at the top reflect and amplify rhetoric at the individual level. Palpable tensions within Indian cities between Muslim and Hindu neighbors—and calculated, hate-motivated mob violence against Muslim “traitors“—reflect and feed Hindu majoritarian policies at the government level.

Within a subcontinent defined by enduring struggles for national self-definition, a hardened and decreasingly secular India interacts with Pakistan’s national identity, and the extent to which it chooses to act upon an ideological anti-Indianism. As the Indian government has quietly but forcefully chosen to identify its Muslim citizens as “internal enemies,” anti-Pakistan rhetoric has increased, further enforcing a false Hindu-Muslim, India-Pakistan dichotomy. As discourse in India has captured this battle of national self-definition, so too have India’s and Pakistan’s postures hardened: Modi has positioned India against Pakistan, including amidst the January protests, and Imran Khan has threatened “false flag” operations in response to an “increasingly expansionist” India. While the BJP may caution against interference in India’s “internal affairs” as its domestic agenda runs its course, a Hindutva-inspired Indian national identity is likely to influence the ongoing process of nation-building on the subcontinent for years to come.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: Wikimedia Commons

Image 2: NurPhoto via Getty Images