My idea of India is dated, like me. I mourn its passing. My idea of India is rooted in my first, eyes-wide-open steps in a country strange and foreign to my sheltered being. It was in the early 1990s. I embrace how India has changed for the better since then. But not everything has changed for the better.

For some context: I arrived on the subcontinent after the Cold War had ended. I had worked to prevent mushroom clouds between the United States and the Soviet Union, and now I carried the toolbox of confidence- and security-building measures to India and Pakistan. My game plan was to present this tool box and ask thoughtful and proud people to have a look, and to consider whether there might be something here worth adapting to the subcontinent’s special circumstances.

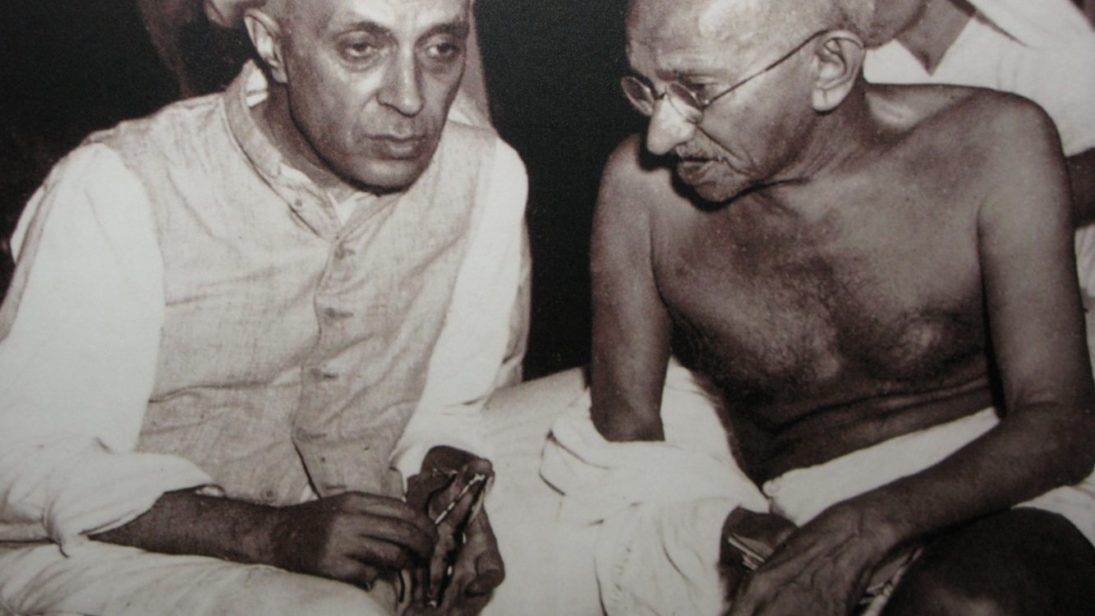

The India I read about was the land of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. I also read about the struggle for independence, and how Gandhi’s non-violent civil disobedience movement shamed British leaders before the entire world. Satyagraha works when rulers have a conscience. It fails when they have no conscience. Satyagraha was Gandhi’s gift to us all. It produced a vibrant experiment in democracy and secularism.

Before me was a kaleidoscope of humanity. I had studied in Cairo after graduate school but still, nothing in my life prepared me for what I saw and experienced in India. The erudition, the cultures and mix of religions, the sheer life force of the place expanded my mind and my horizons.

This amazing patchwork quilt of regions, languages, peoples and religions was engaged in a halting and purposeful struggle toward a more perfect union. My country was, too, but the United States was monochrome compared to India. As hard as it was to fulfill the promise of America, this paled in comparison to India’s struggle to make a more perfect union.

This wasn’t just a noble struggle. I quickly understood that it was a practical one, too. India is so diverse and its weave so complicated, that for the country to thrive it had to bring everyone in. To borrow from V.S. Naipaul, India needed to accommodate continuous mutinies, mostly on a small scale. Except for Muslim-majority Kashmir, an on-going mutiny of geostrategic importance. It was a mutiny of New Delhi’s making, with a significant assist from Pakistan’s military and intelligence services. The Kashmiri mutiny would test and define, more than anything else, India’s concept of itself.

If India were to become a more perfect union — a healthy, democratic, pluralistic, and secular society — New Delhi would have to quell the perpetual mutiny in Kashmir by peaceful, political means. The promise of India is intertwined with the promise that the Indian Constitution granted to Jammu and Kashmir.

If India were to become a more perfect union—a healthy, democratic, pluralistic, and secular society—New Delhi would have to quell the perpetual mutiny in Kashmir by peaceful, political means.

India’s strength lies in its diversity. So, too, does its weakness. The biggest threat to the India I have admired is a Hindu nationalist majoritarianism that disrespects India’s patchwork quilt. A secular, democratic India is a beacon to the world. A Hindu nationalist India is a work in progress. It will foster more mutinies.

Pakistan has made a mess of itself as well as Kashmir. Aiding insurgency in Kashmir seemed to be a low-cost option, but near-term thinking has always been the bane of Pakistan’s existence. The promotion of violence in furtherance of national security objectives has been ruinous to Pakistan. What has Pakistan gained? The answer is evident in the current state of Pakistan’s economic and political life. Its national security and international standing have shrunk considerably. Pakistan’s experiment in democracy has been subverted by dynastic politics and military interventions, leaving its people without the governance they deserve.

The tragedy of poor governance certainly isn’t confined to the subcontinent. It is part of a worldwide phenomenon. Strongmen rule. Beijing “re-educates” its Muslim population. Benjamin Netanyahu’s handling of the West Bank has provided a model to Modi. Moscow’s failings are masked by hyper-nationalist appeals and acts of subversion directed elsewhere. Leaders in Turkey, Hungary, Venezuela, the Philippines and elsewhere violate democratic norms, or what’s left of them. And in my own beloved country, Americans are being set against each other in furtherance of narrow, nativist political ambition.

My responsibility as an American citizen is to help make my country a more perfect union, despite its growing failings. But I am not just an American citizen. I have been granted the gift of foreign travel and I have developed attachments. I love the idea of India that remains firmly rooted in my mind. My life has been enriched by friendships there. I love Jinnah’s dream of Pakistan, which is now a distant memory. I have great respect for Pakistani friends who struggle to reform their country. I have been fortunate to have visited Kashmir and spent time with Kashmiris. I grieve for them and for what India is becoming.

The world, within and outside of India, has become a far more brutish place. My friends, there is no time and space for despair. We have work to do, wherever we live.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image: Ken Wieland via Flickr