Strategic literature has generally posited that in crisis moments the goal of nuclear rivals is to deter direct attacks. This has been termed as a bilateral deterrence model, as both rivals are deterred by each other. A form of this is extended deterrence, where a nuclear-armed nation works to prevent an attack on a third-country ally by a common adversary. These forms of deterrence held throughout the Cold War, a time during which crises primarily involved the two superpowers of the United States and the Soviet Union. With the end of Cold War, the United States emerged as the unipolar power, with security interests spread across the globe. In crises between nuclear rivals, it has directly engaged and attempted to dissuade these foes from attacking each other. This American position as a neutral arbiter between nuclear rivals has been studied by American academic Timothy Crawford within the framework of “pivotal deterrence.” Building on this framework, Moeed Yusuf of the U.S. Institute of Peace explores in his new book the role played by third parties in managing crises and brokering peace between regional nuclear rivals.

Theoretical Insights and Case Studies

Yusuf presents his theory three-actor “brokered bargaining,” or the process of crisis management between two regional nuclear rivals led by the third party. In this model, the actions of regional rivals are taking place on two levels: first, they are aimed at each other; second, they are directed at the third party to influence its choices towards the adversary and achieve their respective policy goals. The third party, meanwhile, is mediating between the regional rivals and directing the crisis towards de-escalation. To illustrate his theory of brokered bargaining, Yusuf delves into detailed study of three India-Pakistan crises, Kargil (1999), Twin Peaks (2001-02), and Mumbai (2008), to apply his framework. He then explores the relevance of the model for cases beyond South Asia. To play the part of the third party, Yusuf focuses on the current unipolar power in the post-Cold War era, the United States, but he claims that other major powers have also coordinated their signaling during India-Pakistan crises. Thus, he postulates that the model will hold even if the United States is replaced as the unipolar power in the future.

Through this model, Yusuf challenges the conventional wisdom that a third party must adopt a clear stance to influence the outcome of a crisis or dispute between two rivals. He posits that because of the nuclear factor, a third party can influence the outcome without taking a clear position, as the third party is more focused on preventing escalation. Additionally, in this three-way interactive exercise, all sides are attempting to influence the choices and behavior of others. This is particularly relevant because it means that Yusuf has moved away from bilateral deterrence framework in analyzing crises in South Asia. Yusuf’s theory seeks to dissect these processes, bringing out the patterns of trilateral engagement as well as the behaviors of states that both determine the course of events during crises and influence their outcomes.

In practice, the job of the third party is tougher, given that it has to take into account reactions of both regional rivals to ensure that a signal to one party does not undermine the message it is conveying to the other. To be a credible broker requires ambiguity, at times withholding information from both or either of the regional rivals.

The third party’s brokered bargaining works in parallel to direct two-way signaling between regional rivals. Both adversaries are aware of the power of the third party to tilt the crisis against them and therefore continually account for the sensitivities and preferences of third party, which is primarily to manage escalation. This three-way interaction exposes the limitations of the much-hyped “strategic independence” of regional nuclear powers. In practice, the job of the third party is tougher, given that it has to take into account reactions of both regional rivals to ensure that a signal to one party does not undermine the message it is conveying to the other. To be a credible broker requires ambiguity, at times withholding information from both or either of the regional rivals.

While studying three crises, Yusuf provides macro context (the larger diplomatic-strategic setting) and micro details (comprehensively researched events and details) of each crisis. Analysis focuses on the micro level, as decision-makers attempt to craft responses given the available information. The larger diplomatic-strategic context is suspended in Yusuf’s analysis—he posits that when a nuclear crisis ensues, normal diplomacy and competition between states take a back seat and crisis diplomacy takes over. He then analyzes each of the three crises through the brokered bargaining framework and finds that the model holds in each instance.

Implications for South Asian Security

Yusuf’s research is directly relevant to those studying conflict in South Asia. He argues that regional rivals rely on the third party to communicate, despite bilateral mistrust with the third party. However, he overlooks the question of what happens when a regional rival refuses to trust the messages being relayed by the third party. Such a question is particularly relevant now because future crises will be occurring in a different world: given the current low trust levels between Islamabad and Washington, the former may find it hard to trust Washington the way that it used to during crises with New Delhi, and this may impact America’s ability to play the role of a third party.

It remains an open question whether there will be direct Washington-Beijing parleys on how to mediate future South Asian crises during peacetime. It is also unclear what would happen if China and the United States disagree on an aspect of a future diplomatic crisis, or even the fundamental questions of the crisis itself.

Though Yusuf provides ample evidence of coordination between the third party and other external powers in earlier India-Pakistan crises, he is silent on the possibility of greater direct communication between the current unipolar power and emerging major countries on crisis management in South Asia. In the crises Yusuf examines, Beijing and Moscow were not competing with Washington to the extent they are now. Moreover, in recent years China has expanded its interests and presence in South Asia, most notably in Pakistan. This Chinese presence will likely be a major factor in conversations between New Delhi and Washington, as well as Islamabad and Washington, during crises. However, it remains an open question whether there will be direct Washington-Beijing parleys on how to mediate future South Asian crises during peacetime. It is also unclear what would happen if China and the United States disagree on an aspect of a future diplomatic crisis, or even the fundamental questions of the crisis itself.

Another important finding of Yusuf is that India had sought a third party role in moments of crisis, having directly signaled to the United States that it seeks its involvement. This finding is contrary to consistent Indian opposition to third party involvement in bilateral engagements with Pakistan. For instance, in the days following Mumbai attacks, as India decided to exercise military restraint it gradually pressed on the “international community” (read the United States) to pressure Pakistan, as it believed that Islamabad would only act under American pressure. According to Yusuf, then Indian External Affairs Minister Pranab Mukherjee even acknowledged this fact to a senior U.S. official, stating, “what little steps Pakistan is taking is because of you.” From a policy perspective, this indicates that as New Delhi’s trust was being built with Washington, it was amenable to its role in crisis diplomacy with Pakistan. Future policy research can explore this space and be expanded in the background of a deepening India-U.S. bilateral relationship.

Conclusion

Yusuf has brought in original framework to study third party engagement in crises. His work has opened room for further theorizing about the role of third parties, particularly in a multipolar world, as an independent variable. It also connects an academic quest with tangible policy dilemmas and deepens our understanding of crisis behavior of regional nuclear powers in combination with a third party. Beyond the present era, the test of this framework will be in a multipolar world: will major powers come together and cooperate to defuse a nuclear crisis between regional rivals regardless of their own global power competition? Or, will they see it as an opportunity to advance their own geostrategic interests?

Editor’s Note: In this four-part series, SAV contributors Tanvi Kulkarni, Joy Mitra, Saima Sial, and Muhammad Faisal review political scientist Moeed Yusuf‘s new book Brokering Peace in Nuclear Environments: U.S. Crisis Management in South Asia (Stanford University Press, 2018). The book traces the history of conflict between nuclear neighbors India and Pakistan and assesses the potential of third parties to prevent nuclear war in South Asia.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

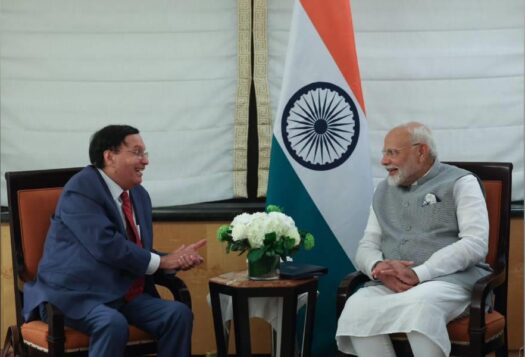

Image 1: IIP Photo Archive via Flickr

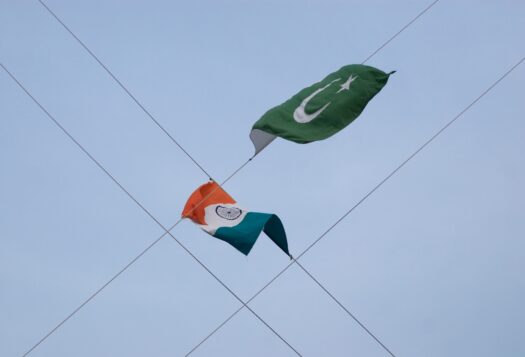

Image 2: Uriel Sinai via Getty