While 2025 has witnessed a stabilization of the Pakistani economy, a transformation in ties with the United States, and a notable defense pact with Saudi Arabia, it has also been marked by national security challenges for Pakistan in the form of militancy and cross-border violence, rising tensions with Afghanistan, and conflict with India. To unpack this complex picture, South Asian Voices spoke with Dr. Syed Hussain Shaheed Soherwordi to understand the drivers of Pakistani security and foreign policy, implications of the latest clashes between Pakistan and Afghanistan, as well as how Islamabad aims to navigate regional geopolitics in 2026. Dr. Soherwordi is Chairman of the the Department of International Affairs and Director of the Center for FATA Studies at the University of Peshawar. His recent book is titled A Divergent Foreign Policy Alliance: The US Towards Military-Ruled Pakistan (1947-1965).

How would you describe the central tenets of Pakistani foreign policy today, and how have they changed from the past? What drives the way Pakistan thinks about its place in the region and in the world?

SHS: Pakistan’s foreign policy today remains guided by several enduring factors, including sovereignty, security, regional stability, and economic diplomacy. Yet it has evolved significantly from its early Cold War era alignments to a more pragmatic multilateral approach shaped by shifting global and regional realities.

During the 1950s, ‘60s, ‘70s, and even during the ‘80s, we were the “apple of the eye” of the United States, but we compromised on our neighborhood. That proved very detrimental to Pakistan’s interests, objectives, and goals. So now, since 2015, when the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) emerged, there was a lot of pressure from the United States to pick a side, which Pakistan has refused to do. Ten years later, the United States seems to accept that Islamabad will not compromise on China and the economic benefits for Pakistan. They’re not putting that kind of pressure on Pakistan anymore, and they seem to understand that if Pakistan is getting close to the United States, it’s not at the cost of China.

Modern Pakistani foreign policy emphasizes geoeconomics over geopolitics, rather than its traditional security-centric perspective. We had SEATO and CENTO in the past, in which we became a frontline ally of the United States. But the post-Cold War and the post-9/11 era spurred Pakistan to reorient its foreign policy approach toward the pursuit of strategic autonomy and regional integration and connectivity through initiatives like CPEC, becoming part and parcel of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and engaging with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Now Pakistan is implementing a more balanced diplomacy, seeking equilibrium in relations with major powers, instead of strict alignment with one bloc.

Finally, in its neighborhood policy, Pakistan increasingly advocates for dialogue and conflict management, especially with India and Afghanistan. It also leans on Islamic solidarity and humanitarian diplomacy, which remain key soft power elements in Pakistan’s global posture.

Ten years later, the United States seems to accept that Islamabad will not compromise on China and the economic benefits for Pakistan. […] [A]nd they seem to understand that if Pakistan is getting close to the United States, it’s not at the cost of China.

How do you see these principles in action in Pakistan’s consequential relationships, such as with the United States, China, Saudi Arabia, and India?

SHS: One manifestation of Pakistan’s shift toward a more pragmatic foreign policy is that the relationship between Pakistan and the United States is now transactional. It is centered more on counterterrorism, stability in Afghanistan, economic concerns, and rare earth minerals, rather than the deep strategic dependence of earlier decades. The China partnership, for its part, has deepened into an all-weather strategic cooperative relationship symbolized by CPEC, reflecting Pakistan’s pivot towards Asia and infrastructure-led growth in this region.

Ties with Saudi Arabia are very important, and remain rooted in religious affinity, energy cooperation, and expatriates. Pakistan increasingly seeks a balance between Riyadh and Tehran: while ties are quite strong with Saudi Arabia, Pakistan is not ready to compromise on Iran because of their shared border. To that end, the recent Saudi-Pakistan defense agreement, under which both countries would consider an attack on one as aggression against the other, shook the entire region. With growing doubts about the value and reliability of the U.S. defense umbrella, this mutual defense agreement is a consequence of the eroding trust of regional states.

Lastly, with regards to India, rivalry persists. Pakistan and India found themselves in the first armed skirmish in six years in May of this year. Indian policymakers continue to accuse Pakistan of fomenting terrorism, while disregarding Pakistan’s own history of suffering terrorist attacks and threat perceptions regarding alleged Indian support of separatist movements in Balochistan. Therefore, Pakistan has been advocating for dialogue over confrontation, especially in global forums, and trying to shift from hard to soft power projection as concerns India.

How does Pakistan think about its relationships with the United States and China? Does Islamabad see those two partnerships in tension, or can they be complementary? How do Pakistani policymakers think about the prospect of intensifying U.S.-China competition, even if the Trump administration’s China policy remains somewhat unclear at the moment?

SHS: It is a very difficult question. Pakistan is walking on a tightrope, balancing both relationships. The current upswing in Pak-U.S. relations marks a notable recalibration after years of strategic drift. The Biden administration had a very clear agenda and Pakistan was in a disadvantageous position at that time. But regular leader-level exchanges that have taken place very recently with the Trump administration have helped renew cooperation in energy, in trade, critical minerals, and rare earth minerals. All of this reflects Washington’s growing recognition of Pakistan’s geoeconomic and geostrategic relevance beyond its traditional lenses: China, Afghanistan, and counterterrorism. For Pakistan, this engagement aligns with its shift towards economic diplomacy and diversification of partnerships under its new geoeconomic vision.

Until recently, Pakistan had found itself more focused on China, but it is beginning to diversify. The United States, in the meantime, is potentially eyeing Pakistan as a stabilizing actor in South Asia, amid China’s expanding footprint through CPEC and shifting dynamics in Afghanistan.

But this warming of ties, while encouraging, may still be more tactical than transformational. Historically, Pak-U.S. ties have been very cyclical and event-driven, leading people in Pakistan to believe that the Americans always have one foot out of the door. This is one of the arguments of those elements in Pakistan’s hierarchy that supported the Afghan Taliban during the Global War on Terror. They always said: “once this is over, the Americans will leave us; we must be prepared for those days.”

That is to say, this event-driven relationship is now being shaped by converging interests rather than deep mutual trust. Unless this cooperation evolves into a sustained institutional and economic framework, including long-term trade agreements, technology transfer initiatives, and rare earth minerals cooperation, it will revert to past patterns once immediate strategic needs fade. The current revival signals a positive reset, but its endurance will depend on whether both sides can move beyond transactionalism towards a mutually beneficial development-centered relationship.

Now, with China, Pakistan has a development-centered relationship that’s mutually beneficial. Deeper than the oceans, higher than the mountains, sweeter than honey, stronger than steel—they are really that close with each other. This is not like the relationship between Pakistan and the United States. However, if worst comes to worst, and Pakistan were to be forced to decide between its great power friends, then it would choose to walk away from the United States. This is because of the support Pakistan is getting from China: the investment and the constancy of the partnership over the course of decades. There is an element of the long game at work too: the 21st century will be the century of Asia, and from that perspective, the future belongs to China.

Let’s move to Afghanistan, considering the rapid developments there over the last few days and what is emerging as quite a complex picture between Islamabad and Kabul this year. On October 9, the Pakistani Air Force conducted strikes on a number of locations in Afghanistan, including Kabul, in an apparent attempt to target TTP infrastructure and the group’s leader, Noor Wali Mehsud. In the following days, these strikes have given way to intense clashes along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. What is the current state of play on the border and how will Pakistan navigate this latest round of tensions with Afghanistan?

SHS: Before answering this question, it is important to understand the recent context behind the October 9 strikes. TTP-linked attacks in Pakistan so far this year have already crossed 600, more than all of 2024, resulting in hundreds of casualties across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province as well as in Balochistan. Pakistan attributes all this escalation to safe havens provided in Afghanistan to the TTP, where an estimated 6,000 to 6,500 TTP militants are believed to operate with impunity despite repeated assurances from the Taliban regime.

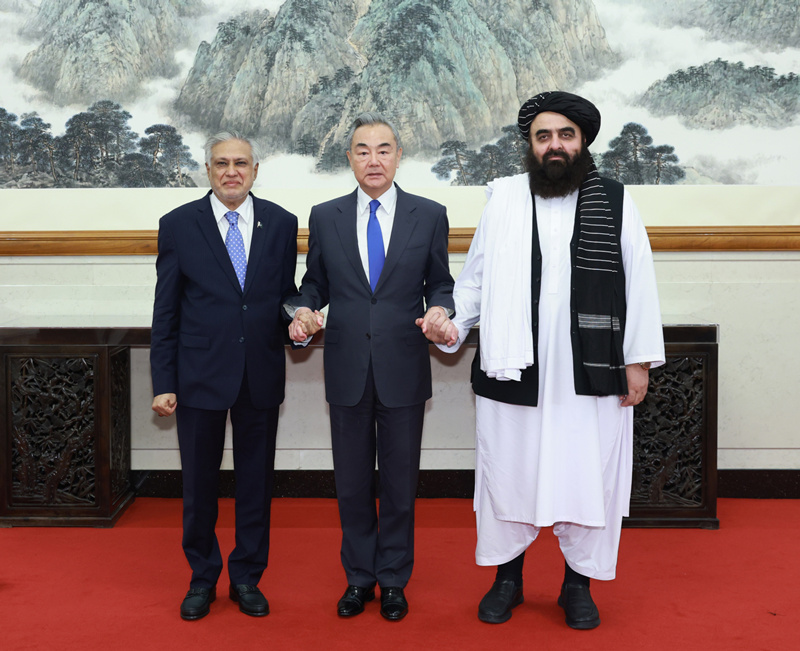

While Pakistan continues to engage diplomatically through trilateral dialogues, including those brokered by China, it increasingly views Taliban reluctance to rein in the TTP as a breach of 2023 border security understandings. In response, Pakistan has also shifted towards selective border closures, and tightened visa regimes, which is really terrible for Afghans who need medical facilities in Pakistan and other trade-related visits. Pakistan has also enhanced fencing operations. This all underscores a preference for security-first engagement rather than broader political accommodation.

Numerous rounds of talks have taken place between the two governments to no avail. Repeated border clashes at Chaman, at Torkham, the expulsion of close to 1.5 million undocumented Afghan refugees from Pakistan, unfulfilled counterterrorism commitments—all of these have strained bilateral trust.

Eventually, when enough was enough, Pakistan carried out surgical strikes inside Afghanistan, which resulted in a near war-like situation in recent days. There is a dire need for diplomacy, as both nations cannot afford war or prolonged tension. The Taliban regime is still in its formative stage and needs the support of its neighbors rather than enmity. Similarly, Pakistan must avoid a two-front situation between India—an existential threat on the east—and Afghanistan on the west.

It appears that the Afghan Taliban understand that there is no alternative stakeholder in Afghanistan that Pakistan can rely on in their place—no mujahideen, no Northern Alliance. Therefore, the Taliban will want to keep Pakistan dependent on them for as long as Pakistan suffers terrorism on its borders.

The Afghan Taliban are generally understood to be divided into two main factions: the Haqqani group, who are more liberal, and the Kandahari group, who are more conservative. Both fear that taking strict action against the TTP will make their respective faction a direct target of the TTP under the command of Hafiz Gul Bahadur, thereby pushing the other faction to align with the TTP.

In light of these tensions within the Taliban, the recent rapprochement between Kabul and New Delhi carries serious repercussions for Pakistan. Pakistan fought alongside the former mujahideen against the Soviet Union during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, primarily to prevent an Afghan-Indian alliance. Later, Pakistan supported the Taliban and challenged the U.S. presence in Afghanistan from 2001 to 2021 for the same reason—to keep India out of Afghan affairs. Now, as the Taliban reach out to New Delhi, with Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi visiting India for several days, it exposes the failure of Pakistan’s Afghan policy over the last five decades. The irony is stark: the Deoband seminary in India, the origin of the Deobandi movement from which the Taliban claim ideological descent, had disowned the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul in August 2021, only to now welcome the Taliban foreign minister. Simultaneously, political relations are improving, with India committing to reopen its embassy in Kabul.

Pakistan’s recent attack has also had the unintended effect of uniting Afghans behind the Taliban regime—the same Taliban notorious for banning girls’ education, women’s employment, and women’s participation in public life. The attack has galvanized Afghan nationalists, who now stand behind the Taliban. Wars often unite nations, and Afghanistan is no exception; a people once divided over the Taliban are now rallying around their flag.

For now, both sides have agreed to a ceasefire, as expected: neither can they live without each other, nor can they afford continued hostilities. Afghanistan depends heavily on Pakistan for economic, social, cultural, political, and even religious support. As a landlocked state that fulfils much of its needs through the Chaman and Torkham border crossings, Afghanistan cannot afford to be hostile toward Pakistan—a country that has long served as its lifeline. But overall, Pakistan has the same demand of Afghanistan it has made for years: halting TTP subversive activities and reigning in of extortion calls from Afghanistan.

Zooming out beyond just the last week, we have also seen greater involvement from China in a trilateral with Pakistan and Afghanistan. There was also some talk about the extension of CPEC to Afghanistan. Given that the security situation continues to be difficult along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border, where do you see this trilateral going? What do you see as the constructive path forward for Pakistan-Afghanistan ties?

SHS: There has been the restoration of ambassador-level representation in the middle of this year and China’s commitment to extend CPEC into Afghanistan, potentially linking Kabul to Gwadar port in Pakistan. These are some of the very positive diplomatic milestones that all three countries can work for. Yet progress has been overshadowed by the resurgence of cross-border militancy.

My understanding of the Afghan Taliban’s position is that they feel a certain solidarity with the TTP that stems from the support and shelter it provided the Taliban before the 2021 U.S. withdrawal; as a result, they are more inclined to protect it now that they are in power instead of heeding the demands of the Pakistani state to crack down on TTP’s activities. I believe that making such a choice would be a terrible mistake considering the 2,340-kilometer-long border shared by Afghanistan and Pakistan. As the saying goes, you can change your friend, but you cannot change your neighbor. So, between that long border and the fact that a large portion of Afghanistan’s trade is done through Pakistan via Karachi, it would really be naive of the Afghan Taliban to choose the TTP at the cost of alienating Pakistan.

Coming back to that trilateral initiative, China’s role as a stabilizing mediator will be crucial because it has deep economic stakes in both countries, and views regional stability as vital to its broader project BRI, one component of which, of course, is CPEC. China has offered development assistance to Afghanistan, contingent on improved border security and facilitation of trade with Pakistan.

However, without tangible steps from the Taliban—such as arresting TTP leaders, intelligence cooperation, and a joint border monitoring mechanism—the trilateral will remain largely symbolic, not practical. So, I believe that a constructive path requires a two-track approach: security cooperation and economic engagement. Economic engagement means focusing on border trade zones, energy connectivity, and people-to-people exchanges, which are really quite low at the moment; Pakistan’s visa-restricted policy is also very detrimental to Afghans.

They must also revive institutional communication beyond intelligence and defense channels, and ensure that local grievances in border communities do not become recruitment tools for militant groups. Only by coupling economic interdependence with mutual security guarantees can the trilateral framework evolve into a sustainable platform for regional stability and for economic benefit.

I believe that 2026 will be a test of Pakistan’s ability to transform its geostrategic position into geoeconomic strength. It will need to make its foreign policy a tool not just of diplomacy, but of national development.

We’ve talked about all these different developments in Pakistani foreign policy over the past year: this huge upswing in ties with the United States, the defense pact with Saudi Arabia, the steady ties with China, these developments with Afghanistan. Could you now look towards the coming year and think about how these developments will play out going into 2026 and what the priorities will be for Pakistan going forward?

SHS: I think 2025 marks quite a pivotal recalibration in Pakistan’s foreign policy as it seeks to redefine its external alignments within a rapidly shifting global order. This is perhaps especially signified by the revival and warming of relations between the United States and Pakistan. Pakistan is not looking at security-centered ties with the United States at all because they do not believe they need it. I believe this four-day fight between Pakistan and India has clearly shown that the weapons produced by China can really give a tough time to the Western weapons employed by India.

Bilateral trade with the United States has already risen by 16 percent in FY2024-2025, reaching USD $7.6 billion, while new U.S.-backed renewable energy and digital infrastructure projects are already underway. This engagement highlights the new economics-first approach that Pakistan has adopted in recent years, focusing more on sustainable development and human security rather than military dependency that Pakistan used to do once upon a time. However, Pakistan also remains quite cautious and mindful that a relationship’s longevity depends on institutionalized economic cooperation rather than short-term strategic convergence.

Simultaneously, the defense pact with Saudi Arabia represents a deepening of strategic and military cooperation in the region. Under this pact, for example, Pakistan has officially agreed to provide military training and defense advisory support, which Pakistan was already providing to Saudi Arabia. But this time, they have signed a formal agreement, which is expected to bring significant annual oil and investment commitments from Saudi Arabia. The deal has bolstered Pakistan’s foreign reserves, which rose to over USD $14 billion by mid-2025, helping stabilize the Pakistani rupee, strengthening Pakistan’s economic resilience. And beyond economics, the pact reinforces Pakistan’s traditional alignment with the Gulf countries and positions it as a regional security partner. Going forward, Pakistan must carefully navigate its commitments to avoid being drawn into intra-Gulf rivalries or conflicts.

Pakistan’s relations with China have returned to steadiness after a turbulent 2023-24, when CPEC was slowed down, and the Chinese were quite worried about their economic investments and security of their projects. The resumption of CPEC project phase two this year, with USD $8.5 billion in new investments, is quite a boost to Pakistan’s economy.

Moving forward, Pakistan’s foreign policy priorities will likely focus on economic revival through regional connectivity and engagement with other groupings (such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Organization of Islamic Countries), energy security, balancing major power relations—e.g. China and the United States. The strategic challenge in 2026 and beyond will be to sustain equidistant diplomacy: leveraging U.S. economic opportunities, Gulf financial backing, and Chinese infrastructural support, while safeguarding national sovereignty and ensuring internal security coherence. Only through this pragmatic diversification and engagement can Pakistan chart a stable and self-reliant trajectory in an increasingly polarized world.

It will also strive to maintain a delicate balance between Washington and Beijing, leveraging both partnerships for economic benefit while avoiding entanglement in great power rivalry. This is a difficult prospect considering how intertwined those avenues for economic benefit are becoming: for example, Pakistan has made commitments with the Chinese on alkaline batteries material exploration in Pakistan, at the same time as they very publicly offer rare earth minerals to Americans. How can we offer two great powers the same thing? This will likely induce a lot of difficult questions for Pakistan in Beijing. Will we be able to answer them? That remains to be seen, and I worry about how Pakistan will manage this going forward, because any misunderstanding will prove itself quite expensive for Pakistan.

In a sense, I believe that 2026 will be a test of Pakistan’s ability to transform its geostrategic position into geoeconomic strength. It will need to make its foreign policy a tool not just of diplomacy, but of national development.

Views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the positions of South Asian Voices, the Stimson Center, or our supporters.

Also Read: Confronting Pakistan’s Deadly Trifecta of Terrorist Groups

***

Image 1: The White House

Image 2: PRC State Council